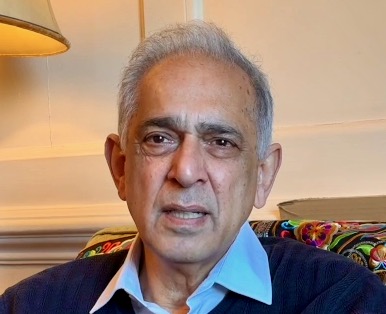

Shailendra Vyakarnam

Duration: 60 mins

Share this media item:

Embed this media item:

Embed this media item:

About this item

| Description: | Interviewed by alan Macfarlane on 7th December 2023 and edited by Sarah Harrison |

|---|

| Created: | 2023-12-28 10:30 |

|---|---|

| Collection: | Film Interviews with Leading Thinkers |

| Publisher: | University of Cambridge |

| Copyright: | Prof Alan Macfarlane |

| Language: | eng (English) |

Transcript

Transcript:

aINTERVIEW WITH SHAILENDRA VYAKARNAM BY ALAN MACFARLANE 7TH DECEMBER 2023

AM

So it's a great pleasure to have a chance to talk once again with Shai Vyakarnam. Shai, I always start by asking when and where you were born.

SV

Certainly, I was born in New Zealand, Wellington in 1952. My parents were amongst the first wave of Indian diplomats after independence. That's what had taken them there.

AM

Fine. Well, let's go back, because I remember you told me an interesting history of your family. Go back as far as you like and fill in a few of the relatives.

SV

Yes, I'll try and do that. So, if we go back about three, four hundred years, I guess, is kind of a broad timeline. It's that as my family were teachers and they were in the big temple there in the north of Bangalore And the circumstances changed as the Muslim invasions came further south. Our ancestors left for Mysore Palace, and established themselves there. And that's where they got the title of Vyakarnam, which basically means grammarian. Vyakarnam. I'm told by my family I shouldn't have the letter M on the end, but never mind. And then from that period on, they were first ministers in the palace. One of them was a civil engineer, Vishweshwaraiah, who is probably the most well-known and respected in South India, especially for having built the hydro- electric dam and various canals, road networks. And he, together with the Maharaja of the time, the early 20th century, the Maharaja is probably one of the last of the princely entrepreneurs., established some 50 businesses between them for sandalwood and leather and all sorts, creating employment for thousands. So, public sector entrepreneurship, if you will.

And then later on, another of our relatives served as the Comptroller and Auditor General of India. (My mistake he was not at the RBI And so those are probably the two most famous of our relatives. We also have had two of the first women graduates of Mysore University in our family, who became school inspectors and were sisters. They were amazing. And so we, luckily, still have photographs of them hanging around. On my mother's side, mostly again teachers and working in colleges and universities. So, there's quite an array of people involved, one way or the other, with the professions and with academia.

AM

Well, tell me about your parents, their character and their background.

SV

Sure. So, both my parents had a degree and they're in CBZ, as it was known as. That's Chemistry, Biology, Zoology. My mother said her marks were higher than my father's! They met through introductions. And then they went off to Bangkok in 1948. First wave, of Diplomats after India's independence. My father was involved in the commercial side of things, to try and find and influence exports from India, engineering exports, to bring in foreign exchange for an emerging economy. From Bangkok, they went by seaplane to Wellington, established themselves there for four years. And they had an interesting time there. I think my father got interested in what he thought were affinities between his mother tongue, Kannada, which is from South India, and Maori. So, he started investigating that and wrote a paper on that as part of his application to, I think it was Cornell. Never went off to do his PhD there, but it is a really interesting paper, which I actually discovered recently on the internet. Somebody's put that up as a library document. So, quite an interesting piece of work. My mother was obviously with him. They were together working on something called 'Made in India'. India now runs 'Make in India', so encouraging investment into India. But back then, again, it's all about exporting and foreign exchange. So, they had all of that going on. They made friends with a local Maori group, which then resulted in me getting, when I was born, getting a name, Tikani Tehua Irihia. Now, what I don't know is how much of that was made up by my dad, who was quite capable of telling stories, or how much of it is actually real, which apparently means little Indian chief of the Tehua tribe. If somebody who is a scholar in that can ever confirm that, I would be most grateful. And from New Zealand, we went back to India. I was about two or three years old at the time. We went on a ship called the S S Oronsay, which was designed to go from London to Australia and beyond on the Pacific route to America.

AM

What date was that?

SV

'54. It was basically a liner that was from across the Pacific to North America, then all the way back by Australia to Ceylon, and then back via the Suez Canal back to England. So, that was its route, and we were on that. It was a strange time, because there was still discrimination based on colour at the time. My parents were probably the only non-whites on the ship. And at every port, the captain would call my father's name out to say, you know, was he there comfortably, and could they please report to the captain's office. Dad went a couple of times and realized what was going on, and said two things to the captain. He said, I'm a diplomat, and I'm taking great offence at your calling me out. And secondly, why would I get off in Australia? It's a country made up of criminals. It has no interest to me whatsoever. And they went back to India. And then we were in Delhi for a little while.

That's 1954 to about 57, 58, around that period, during which time my dad had gone again on a trade mission, this time to China. This is during the Communist Party period, obviously, embedded. And at that time, there was something called Hindi-Chini-Bhai-Bhai, which is Hindi, India, Chini, China, Bhai-Bhai, brother-brother. So it's meant to be some kind of entente cordiale between them. And when dad went up to Beijing, he was vegetarian. So he had quite a struggle to remain vegetarian there. . But he also had lots of winter clothes. And that's where he made his biggest mistake, which is he offered his winter clothes to the translator when he left, or the day before he left. And the next day, he saw the poor man being taken away for correctional education. That was quite tough. That was late 50s.

From Delhi, we moved to Mombasa in Kenya. Again, a trade mission that was much more successful for that, I think. And Mombasa was fantastic, because that's where my own memories are starting to kick in now. I'm about seven years old at this point, seven, eight years old. And I went to the H H Aga Khan High School , a huge establishment. Lliving in Mombasa on what was then called Kilindini Road. It's probably a President somebody or other name now! And for those people who have been to Mombasa, where the big tusks are, the steel tusks that grace the road, we lived roughly around there, next to the Mombasa Times. So every morning, you could hear the presses clattering away. It's a wake-up sound. So there, the methodology was to try and persuade the local farmers and business community, who were mostly from Gujarati, to look at the Indian engineering products.

AM

Was your father a diplomat at that point?

SV

Yes, still. It's all part of the diplomatic mission at this point. He was working for something called the Engineering Export Promotion Council. And they even had a showroom there. So he hosted a number of the emerging presidents, Hastings Banda, various other people from Malawi, Tanganyika, as it was then, and so on and so forth, who would come to say, okay, how could they improve the relationship directly with India, rather than through Britain? So South-South collaborations. So a lot of the big engineering brands of India, Kirloskars, Godrej, etc., they all got a toehold into East Africa through my dad's work. And that was quite nice, water pumps for farming and all sorts of things. Engineering goods. I have a big memory around that time that connects back to Cambridge, actually, decades later.

So it's worth telling now. We went on a huge road trip from Mombasa, part of the trade show thing. So we went to Dar es Salaam from Mombasa, and then from Dar es Salaam towards another town called Arusha, which is the foothills of Kilimanjaro. And on that road is a town called Morogoro. And this was just after the rains, and we were driving in our Peugeot 403 estate. And the front tyres got caught in the lorry ruts and dragged us and hit the embankment. And the embankment was of a farm that grew sisal, which used to be grown for making rope at the time. And then the local family came and helped us out and banged the wing out so we could carry on our journey, first taking photographs of hospitality and so forth. That turned out to be the family where my wife, much later, at Hammersmith, worked next to a person called Johar Raniwala. They were both running Cobra Venom factor columns for people like the late Sir Peter Lachman and, Ian McConnell, who happens to live next door to us. And so I discovered this story with Joher when he came for Peter Lachman’s memorial. And there in the album is a picture of me with Joher's older sister from Christmas 1959. And he's now living here in UK, and his supervisor, Ian McConnell, is our next door neighbour.

AM

Small world.

SV

So really, it's ridiculously small, yes. So from Mombasa, during that time, we went to various other parts as well, including Uganda, to Murchison Falls, Lake Victoria, all of that. Incredible back then, the late 50s, hundreds of elephants everywhere, tall elephant grass, long before the destruction of our environment began. So it's a wonderful time. From Mombasa, we were then transferred to Cairo. So by the age of 10, I was born in New Zealand, lived in India, Kenya, travelled to Tanganyika, Uganda, Ethiopia, and reached via Sudan into Cairo.

And on our journey to Cairo, we went via Addis Ababa. It was a lovely, lovely experience. Khartoum, when we got off the plane, my mum decided she didn't want to stop in Khartoum. It's too hot. Those were the days when you had aerodromes. So as we came through immigration (and) customs, my mum said, no, I'm not stopping. Get the luggage back on. So the luggage came from one end to the other and then put back on the aeroplane. We went through the airport and went back on the plane. But in between times, my father had to go through immigration. The immigration officer then insisted my father's name was Lakshmi Patel, and not LakshmiPathy, because all the Patels were Indian, and therefore all Indians were Patels. And then we got to Cairo. Cairo was fantastic. From my bedroom window, I could see pyramids in the distance. That was awesome. On the top floor near Tahrir Square as it is now. So again, living in a nice area. I went to school there on the island of Zamalek. That school had been established by a mother and daughter duo from England. It's called the Manor House School. But when Nasser came into power, the two ladies left for Lebanon, and the name changed to Port Said School. So that's where I was. And in Cairo, what can you say, it was just that I caught rheumatic fever by swimming in the Suez Canal.

My father then realized that his mail was being intercepted and opened. When he quizzed it, he found out from the postman that yes, indeed, his post was first going for censorship. And then he was told that it was being intercepted. And it was being passed to the Pakistani embassy before being passed to him. So Islamic countries were ganging up against India at that time. And so we asked to go on another tour. We went to Damascus for a big trade show. Then we took a side trip from Damascus to Beirut, from where we sent a telegram to India saying, we need to move the office to Beirut, because all our correspondence is first going into Pakistan. So then that Christmas, we moved too. So we were there just under over two years in Cairo, and moved to Beirut from there. And there was much more freedom. And so I then grew up in Beirut, initially going to a Manor House school, which is still the same two ladies again.

AM

And what was your favourite subject at school?

SV

My favourite subject at school, that I probably took a shine to - geography, I think. And I was messing about a lot, because we were moving places. And I think geography and probably music and language was probably... Because my mum was a musician.

AM

And when you said messing about, what were your hobbies?

SV

We were given a lot of freedom back then to do what we wanted and go where ever. So spending time, maybe in Lebanon, swimming was a good thing for me, because there's lots of swimming pools and of course the sea. And then travelling. Travelling has always become part of me by this time. So with friends, we went off to Aleppo, without parents supervising us. I went off to Cyprus on my own for two or three days, about 13, 14.

AM

Gosh.

SV

Yes. A lot of trust from the parents. And Aleppo was fantastic to visit. Really was a remarkable city. And I think my signature in the visitor book, the guest book, was about three or four pages along from Agatha Christie. She had been there as part of her Murder on the Orient Express. She was researching the route.. So it was quite something. And there was a lot to do and see at weekends, in the evenings. We had lots of friends. It was like an expat community of Indians in Beirut, who are still very much in touch with each other to this day, actually. It's quite fantastic.

AM

One thing, just before I forget, I hope you won't mind me asking, but you mentioned your father was a vegetarian. What caste was he from?

SV

We're Brahmins.

AM

Brahmins, that's what I assumed.

SV

Yes, yes, yes. South Indian. So he's from just north of Bangalore. So he's Andhra, Telugu speaking. My mother is an Iyer, to be getting precise now, south of Bangalore, from Mysore state. And so the two had met in Bangalore.

AM

Tell me something about their characters, because you've told me their successes and doings, but how did their characters influence you?

SV

I think my mother was very calm, calm influence. She loved her music. She played an instrument called the Veena, a South Indian instrument. And she was fairly quiet. She had quite a sense of humour. So she had that calmness about her, for sure. And then she wasn't afraid for a quick retort if she was upset about something, because she would make sure. But she was always polite. Dad has a much sharper tongue, much more abrasive when he wanted to be, could be, and very much an adventurer, I would say. So not really fearing anything or anybody. Very straight. So he fell out with his employer towards the end over some deal that they wanted to do, which he didn't think had integrity to it. So this is where I draw the line.

AM

Did you have brothers or sisters?

SV

No, I'm the only one.

AM

Okay. So you're now about 15.

SV

Yes, in Lebanon.

AM

In Lebanon. This is well before all the troubles in Lebanon.

SV

That's right. We were there through 1967 when the first Arab-Israeli war broke out.

AM

Were you there during that war?

SV

Yes, yes, in Lebanon with blackouts and all sorts of things happening around us. Not quite sure what was happening to us. I shifted from Manor House to another school called Brumanna High School. And that was an odd experience, a fantastic experience, but an odd one, because I was surrounded by boys about three, four years older than me, Palestinians. And so there was much more of an Arab influence in Brumanna coming to a good school. Manor House was more the expats sending their children to that school. So I was now part of a slightly different community. And they were there, why they were there was because their mothers had told them to keep failing their exams. So they would avoid Jordanian conscription in the army. You know, it's a mother's thing, right? So there they were driving cars and all sorts of things, looking at this thing, what is going on here? So they were, I would say, the wealthier Palestinians who had left early on and had diversified assets and things. One of them, still a good friend of mine, lives in the USA now. Brother is a senior medical consultant, in Kuwait. So, both from Gaza.

AM

So, by this time you're sort of specialising in one or two subjects. Were you taking things like A-levels?

SV

So I had my GCSEs and things, or GCEs as they were at that time. And I came to UK and finished off my A-levels in London, just doing economics basically. And taking much more interest by this time.

AM

At a sort of finishing college?

SV

What is it called? London School of something. It wasn't one of these big grammar schools because I was dropped in by, in a parachute if you will, into the system here. So I went where a lot of the international students were going, I can't remember the name, somewhere in Bayswater. Did my economics, was okay. And then I don't think I had that much of a tolerance for the academic side of things. So I went off and did business studies. I did it part-time so I could work as well.

AM

And at Cranfield?

SV

No, I went to Cranfield in the end, but initially to good old Poly. Hendon to begin with, and then Middlesex as they were then. I did quite well in those places, so it was obviously that wasn't the issue for me. It was just what I wanted to do. I was always quite active, so I ended up running the motor-sports club in the college, made and sold candles, tried my hand at minicab driving for a few evenings. All these new novel things that I hadn't experienced or understood before having grown up at home in Lebanon and all that. Suddenly London was this explosion of activity that happened around me. We lived in Golders Green, so I was in and out of central London. You could park in those days on Carnaby Street, imagine that. So I was also old enough to have a driving license, so I was just absolutely everywhere finding my way around. My interest in motor-sport as well had grown because of the big boys in Beirut. So I went off to find out about all of that.

AM

This is post-Beatles, but it's still Carnaby Street.

SV

Oh my God, it was fantastic.

AM 60s, before that.

SV

We came to London in 1969. I just caught up in that anti-war sentiment. Daniel the Red in Paris and so on, and the riots in London. Grosvenor Square, was it?

AM

Yes, Grosvenor Square. I was there.

SV

You were there?

AM

Yes.

SV

So all of this was happening around me, and I could not get my head around it fully, actually. It was quite an explosion of activity. It was fantastic. So I worked at Mobil Oil for a bit, one of their marketing departments, while doing my diploma studies. Then I went off to do management studies, and I started working in the three-day week right after that, in the early 70s. I remember going to work and having a kerosene lamp on my desk, wearing coats and gloves and so on, whilst working in a small engineering company in King's Cross.

AM

That was about 1973, wasn't it?

SV

Yes, that's right, 1973.

AM

Coal miners' strikes and so on.

SV

Yes. I mean, just as an example of the kind of wilder things that happened was that my mum went on a concert tour all the way down to Italy. She and some friends that had just set off in a Land Rover with her instrument and so on. And so the house was left to me. So I decided to, aided and abetted by the skill of a friend of mine, to try and make candles and sell them. So I had three or four rounds of these, and I sold the candles in the restaurants in Hampstead. They were slightly upmarket candles and went down very well. The fourth occasion, however, I nearly set fire to the kitchen by forgetting that I had the candles on because I was busy watching something on television. So at that point, I decided that was it. So my candle-making business came to an end on that. And with motor-sport, I got involved eventually through the 80s with something called the Himalayan Rally. But in 1973-74, things were happening. In 1974, somebody I knew in Lebanon, who was also my age, came to the UK to study because our fathers knew each other. So we were young 20-year-olds by this point, and we started going out and eventually got married as well. So she's now a professor of microbial immunology at King's College in London. And her lab, Annapurna, her lab is in India, so she travels back and forth doing work on it.

AM

You're still married?

SV

Oh yes. Yes, yes, yes.

AM

That's great. Again, I hope you don't mind my asking, but you mentioned your father suffered obvious discrimination on the voyage there. And I read a number of accounts of England in the 50s and 60s when I was there. Did you face any discrimination in your early time in London?

SV

Not on the streets. There were odd things. I had a Saturday job for a time, as you do, and the manager of the shop, Sid Corb, decided that Shailendra, or Shai was too long a name, and that I should be called Charlie. And I said, but my name is Shailendra. He said, do you want the job or not? So that kind of stuff. But the hurling of abuse in my direction, only, I think it might have been once or twice, I just ignored that nonsense. Most recently it was just about lock-down time actually in Bristol, strangely enough, yes. But he was drunk and probably high and again to be ignored. I think there are other forms of discrimination which is being overlooked for promotions and jobs and things. That's way too subtle to pinpoint.

AM

Yes, yes. So at the end of the diploma, what did you decide to do?

SV

I then worked for a few years at an engineering company and then with another, two engineering companies. One was a Victorian old firm called London Shafting and Pulley, which changed the name to LSP Engineers, manufactured conveyors. They took on a Dutch conveyor belt manufacturer, became a Dutch company. So I worked with them for a bit. And then I worked for a German company which was established and based out of Essex, that made drive belts. And in fact, there's another odd connection. That company is called Optibelt. And it turns out that a member of King's, Herman Hauser's grandfather, I think, was a distributor for Optibelt in Austria. And there was I with Optibelt decades later.

AM

That's interesting. Herman's from Austria and came over from Austria. So the family had been here before, obviously.

SV

Yes.

AM

Interesting. I mean, you're trained in business. What do you do in a conveyor belt business? You can't be engineering or anything like that.

SV

So my role there was to ensure that all the supplies came into the company. And because of three-day weeks and all the oil crises and all the rest of it, trying to get all the various components in to manufacture conveyors. So that was the essence. It was a smallish firm, about 100 of us. And it was great fun. I was young and learning so much. So that was a deep dive into one firm. Because it was small enough, I got involved in a number of different things. Later on, I got involved in sales. So that was doing one thing with a lot of products. This was a lot of different things with one company. And then I went to do an MBA at Cranfield. It was '82, 82-83. Our son had just been born in '82.

AM

You've got one child?

SV

Two. And so the second one came in '91. And Cranfield, having done the MBA, it was a full time. In the 80s, Cranfield was one of the top three schools. It was good to get into that, London Business School, Manchester and Cranfield before the Judge and Said came up. But at the end of the MBA, I kind of wondered why I had done the MBA. Because all it seemed to me was about somehow increasing one's income potential.

AM

I'd like you to expand on that because I have a deep scepticism about MBAs.

SV

I think I learned a lot during that one year. It was an intense period. I learned a huge amount about both myself and about the world of business and management, more precisely. So things like operations and marketing and policy and strategy and so on and so forth. There's a huge number of things and organization development. So a lot of the frameworks that we use, I mean, they grandly call them theories in management, basically they're frameworks. And typically an MBA challenges you to reflect on your ability to think and your motivations as well. And you make some good friends from it and some good contact connections, etc. So all of that's a positive side. The other side of it is it's entirely predicated on one kind of model of economics, the free market capitalist model. And you've got no other scope for other ways of thinking about it.

AM

Rational actors promoting their self-interest and all that stuff.

SV

So 1977 was Milton Friedman's major piece of work. As that took root, everybody was into free market economics and nothing else worked. So it's really drumming that in. And being the son of an Indian diplomat slash bureaucrat, I was born into a family that grew up in the Indian way of thinking about things post-war, post-independence, which is much more of a socialist way of thinking. And certainly the legacy of our ancestors and of my parents, perhaps more strongly my father's, was about what's my purpose? Why am I here? What's the point of it all? And this is where this are so many incidents over time, people I've met, people to talk to, stories, anecdotes around me, family, friends, etc. It was commonly dominated by this notion of trying to make a difference. In that context, I couldn’t see what I had got out of this thing. So I ended up doing a PhD on the social relevance of management education.

AM

Social relevance of?

SV

Management education.

AM

Interesting.

SV

So I went down the usual route, economics, value for money and that kind of stuff.

AM

Was this at Cranfield?

SV

At Cranfield, yes. The excellent supervisor, Malcolm Harper, Oxford and Harvard and then family business, etc. He did his PhD in Nairobi on small business and entrepreneurship.

So in that case, you turn the handle to the right and you get a kind of value for money argument. You turn the handle to the left, economics, Latin American economists and so on that I read extensively at that time. I think, I don't know if I can answer anything with this. So I abandoned both after about a year and went off to read George Kelly's work in psychology, construct theory. I thought how people construe the world probably influences their behaviour eventually. It's been shown by Bandura and others subsequently. And so that was a really wonderful, insightful period for me. And also...

AM

Was that part of the thesis or did you abandon the thesis?

SV

No, no. I did a PhD at Cranfield. All this reading was all around, this huge amount of reading. And then I did about 120 interviews all in India, which is where the big question was because there was a huge amount of subsidy for management education in India at that time. And I thought, well, what if the taxpayer was really very, very poor and India is subsidizing a whole bunch of middle class people to get elite education? What are they getting back for it? Not what's the MBA student getting back for it, what's society getting back for it? Anyway, so from my point of view, that gave me a sense of direction. So then I decided to work in the world of entrepreneurship, taking all these grand management concepts that I'd learned for a year, and that I'd previously experienced as well, saying how do I apply that to people who are trying to start companies? So the kind of philosophy was not about how to make the rich more rich through all the sophisticated management tools, but how to make the poor less poor by applying some of these principles.

AM

And the Grameen Bank system?

SV

Yes, that was all coming up at that time, late 80s, that's right. And they were trying to find ways of providing micro-finance and so on. My supervisor, Malcolm Harper, was very much involved in that part of the movement in the early days. But I was interested in the education learning side. So I had two main operations going at that stage. One was to work with small businesses in the UK. And the other was going to Nairobi on an annual basis and running a program there for promoting entrepreneurship to educators. So teaching teachers how to teach, if you will. So we had people from about 15, 20 different African sub-Saharan countries coming on our course, Cranfield course, and giving them the tools with which they could then go off and promote entrepreneurship to communities. In the townships, Khayelitsha, Soweto, etc.,

AM

Can you, for my wider audience, explain very simply what is an entrepreneur is and why they are of benefit in a modern society?

SV

Yes, of course. The entrepreneur is somebody, in my definition, there's so many definitions, my perspective on this, is somebody who actually takes an idea and takes it right the way through to the time that people start benefiting from whatever it is that they're offering. So if it's a social venture, it could be better farming or something. But in the case of a day-to-day product, it might be something that they're able to sell into the environment. And there are many different varieties of them. The micro-enterprise or the micro-entrepreneur might just take bulk and then break it down into smaller units and just sell small amounts of toothpaste, small amounts of soap powder, whatever it is, a really micro-enterprise trader thing. You might then get highly educated PhDs and post-docs of places like Cambridge, starting companies that then eventually turn into millions of sales for people, millions of people benefiting from them. And of course people making money from it as well.

AM

But it's all within the framework of capitalism. It's not...

SV

Okay, so that's an interesting point. Sorry to have interrupted you. So the entrepreneur, that would be the definition. But if you said what is entrepreneurial behaviour, that does not have to be within the framework of capitalism. That could just be somebody who is mimicking the behaviours typically of the entrepreneur, but is more generative in terms of what they're doing.

AM

So you have entrepreneurs in Maoist China?

SV

Indeed. I think a lot of them were there already. But in terms of the current context, I think the big challenge for people in economics especially, is to try and figure out how to mitigate for rampant capitalism. I think that has taken root to the extent that we see what's happened to climate. And that's around the... getting a bit philosophical now, but the idea of our value chain, which says we'll take these raw materials, convert them into product, sell them, and then keep doing that and keep selling product without worrying about the consequences on the system. And that has resulted in this one way value chain. And now people talk about circular value chains where there's more regeneration, repurposing, recycling, reusing, and so on. I don't think we've got our head around how that works in terms of the economic system that has to support it. So there's a lot of so-called green-washing that's taken root, and other ways of concealing the old habits.

AM

And then that is one of the major faults of capitalism, the ecological effects. The other is inequality.

SV

Oh, indeed.

AM

Growing inequality. Is there any work... well, there must be a lot of work being done on how to mitigate the effects of Peter's Law or whoever it is to those that have shall be given.

SV

Yes, I think there's still a lot of work that needs to be done because the dominance of, I would call it Friedmanite thinking, is so powerful. So even the political parties now in the UK, both the Tories and Labour, are without imagination talking about growth as a solution to all problems. That's just not enough. Where is the word sustainability? Where is regeneration? Where is equality? And this notion of levelling up, which keeps on coming up. Nobody's actually doing anything seriously about that. So the policy makers and economists in particular, and maybe the civil society agencies, need to get more engaged in trying to bring this about. We're a long way from that.

AM

One thing I didn't ask you, I usually ask people when they're in their teens, because in a Christian society that's the time you get confirmed and I and others become most religious in the Western monotheistic sense. But you're presumably a Brahmin.

SV

Yes.

AM

And does that mean a lot to you? Do you practice Brahminic rituals and so on? Births, deaths, marriages, weddings.

SV

We would practice some of that. I would say, if I had to define myself, I'm a Hindu, without question. I certainly don't wear the sacred thread that I'm supposed to be wearing as a Brahmin, other than at functions. It might be simply that it annoys me rather than anything else. I think the caste system is not one that I take too seriously.

AM

For example, the usual question, you've got a son, have you got a daughter?

SV

Yes.

AM

And if, I don't know if they're married, but if they're married, you wouldn't mind who they married?

SV

Well, my son is married to a Sikh girl, a North Indian girl. And she would be defined as a Punjabi Jat. So not a Brahmin. And that's fine. Okay, it caused a slight rumble, perhaps in the beginning to work out what was what. But they have our blessings, lovely, lovely daughter in law, gorgeous two grandchildren. They're happy. And our daughter is very much a free thinking young woman living in Bristol, working in cyber-security. And quite what she will do, we're not sure. We try to encourage her. But we're not obsessing over the Brahmin thing. No.

AM

Interesting. So at the end of the PhD, what did you do?

SV

I got a lectureship at Cranfield.

AM You'd obviously done a very good thesis and it was commended by the examiners.

SV

All of that. Yes, yes. Thank you. Yes, that's a memory. A happy memory. Yes, this was in ' 86, I think. It was when I started my career. I was at Cranfield for 10 years. And then I got itchy feet. And I, went off to Nottingham Trent University.

AM

Just tell me about the 10 years. They were productive and happy?

SV

Yes, absolutely. So I got into the entrepreneurship - the enterprise group. I was initially part of the agricultural college which Cranfield had. Then moved back to the main campus. And then became a lecturer in enterprise.

AM

Right. And then you went on to Nottingham?

SV

Nottingham. I went from being lecturer to becoming professor there. Set up a group for growing businesses, sponsored by an accounting firm called BDO, Stoy Hayward. But I think my main accomplishment there was to set up the Africa Centre for Entrepreneurship and Growth, which was due to be set up in Nairobi with Malcolm's other PhD student, his last one, Francis Neshamba. So I was Malcolm's first student, Francis was his last student. We came together and we were both very keen on trying to help African students get their PhDs so that they could have deeper entrepreneurship. So we'd been doing short courses. And I felt after a while, actually, unless you have Africans with PhDs understanding this, they can't build up departments in the universities and institutions and so on. So we needed to have a doctoral program. Malcolm kindly came on board as well as playing a second supervisor role. He was retired by then. And we had about 10 people go through the centre. And then towards the end of those five years, I love the atmosphere at Nottingham Trent. But it was a hell of a commute, 88 miles each way.

AM

From where? Where were you living?

SV

I continued to live in Cambridge. Towards the end of my stay at Cranfield, we bought our house . And so, you know, children's education, all that going on. And my wife was in London. So we were both commuting north and south from Cambridge. It's quite a time. And so at Nottingham Trent, I designed something called an MBA for entrepreneurs. And I was due to pitch that to the advisory committee. And about 10-15 minutes before I went to do my pitch to this body of other professors and so on, administrators, I got a call from a gentleman called Peter Hiscocks. He said, do you fancy coming to work with me at Cambridge? Two thoughts went through my head. I thought, is the Pope Catholic. And oh my God, now what do I do with my presentation to the academic board on the third or fourth floor or whatever it was? So I had about nine minutes to decide whether to go in full guns blazing. We need an MBA for entrepreneurs. So I was saying, well, here's an idea that I'd like you to think about. And it's the latter, which I did. And so I had a fully designed MBA for entrepreneurs in my briefcase. Met Peter Hiscocks, got the job as a deputy, as director of teaching and training in the practice of enterprise. So complete mouthful! That was in 2001. And over about two years, we did lots of experimentation. And then Herman made a donation to the university, which then caused a split in the entrepreneurship centre. The bit that he also wanted to see happen is more technology commercialization. So those funds went to what is now called Cambridge Enterprise and the Hauser Forum on the West Cambridge site. And the bit I was in, the teaching bit, remained in the Judge Business School.

So then we're kind of a bit without direction and without any particular sense of identity. So over a few weeks, I thought about this and came up with an idea, which I persuaded Professor Sandra Dawson to adopt, which is that we would establish a centre for entrepreneurial learning on the basis you can't teach stuff that people don't want to learn. And the vision statement is to spread the spirit of enterprise. Because again, I didn't think Cambridge people wanted to learn the tools and techniques, but what they want to do is to understand why. And therefore from that, they would then go off and figure things out. So 2003, that's what we set up. And I became effectively the founding director of the Centre for Entrepreneurial Learning, which is now the entrepreneurship centre of the Judge. And that MBA for entrepreneurs was still in the back of my mind. When I came to Cambridge, of course, I went to see the Dean, Sandra Dawson, talked about the possibility of this and took about two sentences, I think, to kill it dead. Because there's obviously a flagship MBA at the Judge, which is beginning to grow. Last thing they needed was a distraction to it. So a year or two later, having seen the advanced certificate and diploma in manufacturing and management, ACDMM, run by the Institute for Manufacturing, I thought, oh, this is an interesting model for entrepreneurship, very practice oriented thing. So I redesigned the original thing that I had into a modular approach, which is everything you need to know before starting, and then growing your business. And we will then pick out bits of knowledge that you need for your journey, And so we launched that as the diploma in entrepreneurship. And now that's the master's in entrepreneurship, and I believe has some participation here at King's, some of the students are members of King's. So that's a long journey from Nottingham Trent.

AM

And it's been pretty successful?

SV

It's very successful now, yes. And for the university, it's very successful, and for the business school. For me, I think we're missing something. It's no longer an inclusive product. The moment you wanted to have College affiliation, you need to ramp up the grade requirements for people entering. You need to be much more academic. And therefore, you're not dealing with people's lives and aspirations or what they want to start. And you're making it, again, elitist. So it's only the young, rich kids who can afford to come on the course.

AM

It's very expensive, isn't it?

SV

If you have a diploma at £12, 15,000, perhaps, one price point, you're up at about 30 or 40k, it's a different price point. And you're much more, yes, (you can claim) I have my master's in entrepreneurship from Cambridge, as opposed to I learned something to start a company. It's of course, there's the extra value of Cambridge affiliation. So I have mixed feelings about it. I'm glad that it's successful. It's something I started, carrying on as a legacy. I just feel it's missing the inclusiveness of people across society.

AM

And the diploma never happened?

SV

It did. It's the one that's evolved into the master's.

AM

Oh, I see. But it shifted into the master's?

SV

Yes.

AM

So the cheaper version is not available anymore.

SV

Correct.

AM

Yes. I remember you did have some criticisms of the Judge when we last talked, and you may not want to air them on this, and we can talk about them later. But going back to your early reflections on what is the point of it all, do you feel that the Judge and the other business schools are worth preserving?

SV

I think business schools have a place. They do have a place. But I think they lose it when they try to pretend to be all academic. I mean, it is actually, you know, it's like a professional medical degree or a law degree or something like that. You need to have practice there. And I think where the Judge is fighting its corner, if you like, on the international market for MBA qualifications, you're up against the Harvards, the Oxfords, and all the rest of it. I think it does a damn good job in that field.

But I'm not sure, I may be out of touch, so with that little proviso, I'm not sure how well embedded it is into the life of Cambridge. So the Centre for Entrepreneurial Learning was an outward-looking agency. That was deliberately outward facing. We ran our courses in the engineering department, in chemical engineering, in the physics department, in Cambridge, and so on. That is, we would go out there. But I think one of the differences, artistic differences, was the Dean who took over wanted the centre of gravity to be the Judge.,

It's to bring people in. And I'm afraid it doesn't happen. People don't want to come into the business school. They want the business school people to go outside and be with where they are. So I think it's missing that. And the flagship was a course that I ran called Enterprise Tuesday, which we ran in lecture theatre zero in the engineering department for the, (Cambridge alumni might remember that), had about 3 or 400 seats in it. It was packed on a regular basis. That's now shrunk down to a lecture theatre inside the Judge business school. And so it doesn't carry the same atmosphere. There are other courses which continue which are successful, Enterprise Tech and this, that, and the other. But that idea that people should go to the Judge if they want knowledge, as opposed to the Judge saying, we're coming out to see you, there's the difference.

Your wider question about business schools, yes, they're there. They will always be there. Some will be better than others, depending on who is the dean is at the time, where faculty is focused.

There is a farmer friend of mine from Kent, William Alexander, one weekend at Cranfield many, many years ago now, when I was going on about something in marketing, he turned around to me and he said, Shai, in a very great big booming voice, he said, you have departments in business schools, we have problems in business. So we had to take a much more of a holistic approach.

AM

Well, we've got about ten minutes. And I wondered if we could just widen it out to one or two reflections on where the world is now. Any reflections on one obvious thing is the tilting of the world, economically and politically, and in many ways, from the West to the East, the rise of the South and the East, and particularly China and East Asia. Do you have any thoughts about where that is going and whether it can be done peacefully and so on?

SV

I think it's happening. I think the Western commentators are not, just don't have visibility of the progress that's being made. In fact, I put a little piece in on my LinkedIn thing not so long ago, about the ‘just get on with it kind of mentality’ that I saw. So in Bangalore recently, a couple of months ago, I was looking out from the balcony and just looking every morning with my coffee, just looking at life happening, modelled around the books of a gentleman called R.K. Narayan and his Malgudi Days and things, what I observed.

And the penny dropped for me then that approximately 1.3 billion people didn't care to be compared with how well USA or Japan or anybody else was doing. They just wanted to be doing better today than they were yesterday. And so they had a very different metric. And they were innovative, they were inventing. There was a pace of life around what I saw happening. And I thought this is interesting for me to see that they were not bothered about what anybody else thought. So while the CNNs of this world, the BBCs and what have you are all commenting and comparing, and economists are doing, you know, BRICS countries and this and that, for those 1.3 billion people, they're just getting on with life. And I suspect exactly the same is true of China and other parts of the world. And because they're so enthusiastically progressing their own lives, I think they will quietly just overtake what's going on elsewhere. I don't know whether there's any merit in that. But it certainly feels like that to me. And I saw, again, the same, in the UAE, I flew through there, I went to see my son, he lives in Dubai at the moment. They have a vision for 2071 now. It's a 50 year vision. And they're moving away from tourism and retail, more towards technology and climate. That's a clear direction being provided. So I think you're right. There are other centres of gravity now coming. I have no idea about further east because I've not been to China recently or Korea, Taiwan, etc. But among the big economies, it certainly feels that there's a different type of progress being made.

AM

Well, I was going to ask about China because we've just come back from an 18th visit to China, but you're right about, they couldn't care, you know, Ukraine. Well, they do discuss Ukraine and Gaza and so on, but the economic threats and so on are far away and the mountains are high and so on. But one aspect of China which is argued over is whether it's had a good or is having a good effect in Africa.

SV

Indeed.

AM

And I wonder what your thoughts were on that.

SV

Well, I think they're certainly aggressively progressing their agenda. And I don't think that's going to be good news long term. I think there's no... Let me go back to the Tanzam Railway. It links back to my father, who lobbied the Government of India to build a railway. He had written a note to the then government of India saying, you should finance and support Zambia, Tanganyika as it was then, to build a railway because they will be forever our friends then. That was kind of the approach. And of course, the Chinese have built that railway. And that's way more aggressively done and it's causing those countries to be indebted to China. And that's a different form of colonialism. And I don't know how well that will go down in the years to come. People are doing fine now. Sri Lanka is struggling, I believe, to pay back the debts it owes to China. So it is a different form of colonial grip. That's the way it feels from where I see it.

AM

Well, we'll discuss it later. We're just coming to the end. Are there any things that you would have liked me to ask you about that I haven't covered?

SV

I think probably the two other big influences on me that need special attention are my mother and my wife, I would say. Because without them, I wouldn't have been able to do what I did. My mother's influence is, I guess, a contribution to my aesthetic sense, music, and being more tolerant, perhaps, than my father wasAnd my wife's contribution, seeing her sheer energy to get things done, and her commitment also to make things happen, her care for the family, intense care, I would say, for the family, has meant that I've been able to do things that I might not have otherwise been able to do. It's the amount of energy she's brought home.

AM

And you are now, what age, 60?

SV

No, just across 70.

AM

70. So you're retired.

SV

Yes, well, a failed retirement project. Yes, retired. Drawing a pension, I would say, but as one of my friends in Malaysia put it, put it as going into Act Two.

AM

Yes, or the Third Age.

SV

Indeed.

AM

So you're still very active.

SV

Indeed, yes.

AM

And what is your current main project?

SV

The three, the one at the University Library at Cambridge, curating an innovation section, goes under the name of Cambridge History of Innovation Project. That's one. The second one is much more of a mentor than educator. So I've got half a dozen companies I'm helping and supporting, and made one or two small investments in them. We'll see what happens with that. The third one is I've become a co-founder now of a company, and that's a very complex one, which is about using, well, in layman's terms, pressure cooking waste plastic into synthetic oil, so it can go back into the materials industry. And that is definitely a complex project, and one that I would love to see happen.

AM

So every day you wake up with excitement.

SV

Oh, always.

AM

Lovely. Well, that's a very nice moment to end. And thank you very much indeed for a lovely interview.

AM

So it's a great pleasure to have a chance to talk once again with Shai Vyakarnam. Shai, I always start by asking when and where you were born.

SV

Certainly, I was born in New Zealand, Wellington in 1952. My parents were amongst the first wave of Indian diplomats after independence. That's what had taken them there.

AM

Fine. Well, let's go back, because I remember you told me an interesting history of your family. Go back as far as you like and fill in a few of the relatives.

SV

Yes, I'll try and do that. So, if we go back about three, four hundred years, I guess, is kind of a broad timeline. It's that as my family were teachers and they were in the big temple there in the north of Bangalore And the circumstances changed as the Muslim invasions came further south. Our ancestors left for Mysore Palace, and established themselves there. And that's where they got the title of Vyakarnam, which basically means grammarian. Vyakarnam. I'm told by my family I shouldn't have the letter M on the end, but never mind. And then from that period on, they were first ministers in the palace. One of them was a civil engineer, Vishweshwaraiah, who is probably the most well-known and respected in South India, especially for having built the hydro- electric dam and various canals, road networks. And he, together with the Maharaja of the time, the early 20th century, the Maharaja is probably one of the last of the princely entrepreneurs., established some 50 businesses between them for sandalwood and leather and all sorts, creating employment for thousands. So, public sector entrepreneurship, if you will.

And then later on, another of our relatives served as the Comptroller and Auditor General of India. (My mistake he was not at the RBI And so those are probably the two most famous of our relatives. We also have had two of the first women graduates of Mysore University in our family, who became school inspectors and were sisters. They were amazing. And so we, luckily, still have photographs of them hanging around. On my mother's side, mostly again teachers and working in colleges and universities. So, there's quite an array of people involved, one way or the other, with the professions and with academia.

AM

Well, tell me about your parents, their character and their background.

SV

Sure. So, both my parents had a degree and they're in CBZ, as it was known as. That's Chemistry, Biology, Zoology. My mother said her marks were higher than my father's! They met through introductions. And then they went off to Bangkok in 1948. First wave, of Diplomats after India's independence. My father was involved in the commercial side of things, to try and find and influence exports from India, engineering exports, to bring in foreign exchange for an emerging economy. From Bangkok, they went by seaplane to Wellington, established themselves there for four years. And they had an interesting time there. I think my father got interested in what he thought were affinities between his mother tongue, Kannada, which is from South India, and Maori. So, he started investigating that and wrote a paper on that as part of his application to, I think it was Cornell. Never went off to do his PhD there, but it is a really interesting paper, which I actually discovered recently on the internet. Somebody's put that up as a library document. So, quite an interesting piece of work. My mother was obviously with him. They were together working on something called 'Made in India'. India now runs 'Make in India', so encouraging investment into India. But back then, again, it's all about exporting and foreign exchange. So, they had all of that going on. They made friends with a local Maori group, which then resulted in me getting, when I was born, getting a name, Tikani Tehua Irihia. Now, what I don't know is how much of that was made up by my dad, who was quite capable of telling stories, or how much of it is actually real, which apparently means little Indian chief of the Tehua tribe. If somebody who is a scholar in that can ever confirm that, I would be most grateful. And from New Zealand, we went back to India. I was about two or three years old at the time. We went on a ship called the S S Oronsay, which was designed to go from London to Australia and beyond on the Pacific route to America.

AM

What date was that?

SV

'54. It was basically a liner that was from across the Pacific to North America, then all the way back by Australia to Ceylon, and then back via the Suez Canal back to England. So, that was its route, and we were on that. It was a strange time, because there was still discrimination based on colour at the time. My parents were probably the only non-whites on the ship. And at every port, the captain would call my father's name out to say, you know, was he there comfortably, and could they please report to the captain's office. Dad went a couple of times and realized what was going on, and said two things to the captain. He said, I'm a diplomat, and I'm taking great offence at your calling me out. And secondly, why would I get off in Australia? It's a country made up of criminals. It has no interest to me whatsoever. And they went back to India. And then we were in Delhi for a little while.

That's 1954 to about 57, 58, around that period, during which time my dad had gone again on a trade mission, this time to China. This is during the Communist Party period, obviously, embedded. And at that time, there was something called Hindi-Chini-Bhai-Bhai, which is Hindi, India, Chini, China, Bhai-Bhai, brother-brother. So it's meant to be some kind of entente cordiale between them. And when dad went up to Beijing, he was vegetarian. So he had quite a struggle to remain vegetarian there. . But he also had lots of winter clothes. And that's where he made his biggest mistake, which is he offered his winter clothes to the translator when he left, or the day before he left. And the next day, he saw the poor man being taken away for correctional education. That was quite tough. That was late 50s.

From Delhi, we moved to Mombasa in Kenya. Again, a trade mission that was much more successful for that, I think. And Mombasa was fantastic, because that's where my own memories are starting to kick in now. I'm about seven years old at this point, seven, eight years old. And I went to the H H Aga Khan High School , a huge establishment. Lliving in Mombasa on what was then called Kilindini Road. It's probably a President somebody or other name now! And for those people who have been to Mombasa, where the big tusks are, the steel tusks that grace the road, we lived roughly around there, next to the Mombasa Times. So every morning, you could hear the presses clattering away. It's a wake-up sound. So there, the methodology was to try and persuade the local farmers and business community, who were mostly from Gujarati, to look at the Indian engineering products.

AM

Was your father a diplomat at that point?

SV

Yes, still. It's all part of the diplomatic mission at this point. He was working for something called the Engineering Export Promotion Council. And they even had a showroom there. So he hosted a number of the emerging presidents, Hastings Banda, various other people from Malawi, Tanganyika, as it was then, and so on and so forth, who would come to say, okay, how could they improve the relationship directly with India, rather than through Britain? So South-South collaborations. So a lot of the big engineering brands of India, Kirloskars, Godrej, etc., they all got a toehold into East Africa through my dad's work. And that was quite nice, water pumps for farming and all sorts of things. Engineering goods. I have a big memory around that time that connects back to Cambridge, actually, decades later.

So it's worth telling now. We went on a huge road trip from Mombasa, part of the trade show thing. So we went to Dar es Salaam from Mombasa, and then from Dar es Salaam towards another town called Arusha, which is the foothills of Kilimanjaro. And on that road is a town called Morogoro. And this was just after the rains, and we were driving in our Peugeot 403 estate. And the front tyres got caught in the lorry ruts and dragged us and hit the embankment. And the embankment was of a farm that grew sisal, which used to be grown for making rope at the time. And then the local family came and helped us out and banged the wing out so we could carry on our journey, first taking photographs of hospitality and so forth. That turned out to be the family where my wife, much later, at Hammersmith, worked next to a person called Johar Raniwala. They were both running Cobra Venom factor columns for people like the late Sir Peter Lachman and, Ian McConnell, who happens to live next door to us. And so I discovered this story with Joher when he came for Peter Lachman’s memorial. And there in the album is a picture of me with Joher's older sister from Christmas 1959. And he's now living here in UK, and his supervisor, Ian McConnell, is our next door neighbour.

AM

Small world.

SV

So really, it's ridiculously small, yes. So from Mombasa, during that time, we went to various other parts as well, including Uganda, to Murchison Falls, Lake Victoria, all of that. Incredible back then, the late 50s, hundreds of elephants everywhere, tall elephant grass, long before the destruction of our environment began. So it's a wonderful time. From Mombasa, we were then transferred to Cairo. So by the age of 10, I was born in New Zealand, lived in India, Kenya, travelled to Tanganyika, Uganda, Ethiopia, and reached via Sudan into Cairo.

And on our journey to Cairo, we went via Addis Ababa. It was a lovely, lovely experience. Khartoum, when we got off the plane, my mum decided she didn't want to stop in Khartoum. It's too hot. Those were the days when you had aerodromes. So as we came through immigration (and) customs, my mum said, no, I'm not stopping. Get the luggage back on. So the luggage came from one end to the other and then put back on the aeroplane. We went through the airport and went back on the plane. But in between times, my father had to go through immigration. The immigration officer then insisted my father's name was Lakshmi Patel, and not LakshmiPathy, because all the Patels were Indian, and therefore all Indians were Patels. And then we got to Cairo. Cairo was fantastic. From my bedroom window, I could see pyramids in the distance. That was awesome. On the top floor near Tahrir Square as it is now. So again, living in a nice area. I went to school there on the island of Zamalek. That school had been established by a mother and daughter duo from England. It's called the Manor House School. But when Nasser came into power, the two ladies left for Lebanon, and the name changed to Port Said School. So that's where I was. And in Cairo, what can you say, it was just that I caught rheumatic fever by swimming in the Suez Canal.

My father then realized that his mail was being intercepted and opened. When he quizzed it, he found out from the postman that yes, indeed, his post was first going for censorship. And then he was told that it was being intercepted. And it was being passed to the Pakistani embassy before being passed to him. So Islamic countries were ganging up against India at that time. And so we asked to go on another tour. We went to Damascus for a big trade show. Then we took a side trip from Damascus to Beirut, from where we sent a telegram to India saying, we need to move the office to Beirut, because all our correspondence is first going into Pakistan. So then that Christmas, we moved too. So we were there just under over two years in Cairo, and moved to Beirut from there. And there was much more freedom. And so I then grew up in Beirut, initially going to a Manor House school, which is still the same two ladies again.

AM

And what was your favourite subject at school?

SV

My favourite subject at school, that I probably took a shine to - geography, I think. And I was messing about a lot, because we were moving places. And I think geography and probably music and language was probably... Because my mum was a musician.

AM

And when you said messing about, what were your hobbies?

SV

We were given a lot of freedom back then to do what we wanted and go where ever. So spending time, maybe in Lebanon, swimming was a good thing for me, because there's lots of swimming pools and of course the sea. And then travelling. Travelling has always become part of me by this time. So with friends, we went off to Aleppo, without parents supervising us. I went off to Cyprus on my own for two or three days, about 13, 14.

AM

Gosh.

SV

Yes. A lot of trust from the parents. And Aleppo was fantastic to visit. Really was a remarkable city. And I think my signature in the visitor book, the guest book, was about three or four pages along from Agatha Christie. She had been there as part of her Murder on the Orient Express. She was researching the route.. So it was quite something. And there was a lot to do and see at weekends, in the evenings. We had lots of friends. It was like an expat community of Indians in Beirut, who are still very much in touch with each other to this day, actually. It's quite fantastic.

AM

One thing, just before I forget, I hope you won't mind me asking, but you mentioned your father was a vegetarian. What caste was he from?

SV

We're Brahmins.

AM

Brahmins, that's what I assumed.

SV

Yes, yes, yes. South Indian. So he's from just north of Bangalore. So he's Andhra, Telugu speaking. My mother is an Iyer, to be getting precise now, south of Bangalore, from Mysore state. And so the two had met in Bangalore.

AM

Tell me something about their characters, because you've told me their successes and doings, but how did their characters influence you?

SV

I think my mother was very calm, calm influence. She loved her music. She played an instrument called the Veena, a South Indian instrument. And she was fairly quiet. She had quite a sense of humour. So she had that calmness about her, for sure. And then she wasn't afraid for a quick retort if she was upset about something, because she would make sure. But she was always polite. Dad has a much sharper tongue, much more abrasive when he wanted to be, could be, and very much an adventurer, I would say. So not really fearing anything or anybody. Very straight. So he fell out with his employer towards the end over some deal that they wanted to do, which he didn't think had integrity to it. So this is where I draw the line.

AM

Did you have brothers or sisters?

SV

No, I'm the only one.

AM

Okay. So you're now about 15.

SV

Yes, in Lebanon.

AM

In Lebanon. This is well before all the troubles in Lebanon.

SV

That's right. We were there through 1967 when the first Arab-Israeli war broke out.

AM

Were you there during that war?

SV

Yes, yes, in Lebanon with blackouts and all sorts of things happening around us. Not quite sure what was happening to us. I shifted from Manor House to another school called Brumanna High School. And that was an odd experience, a fantastic experience, but an odd one, because I was surrounded by boys about three, four years older than me, Palestinians. And so there was much more of an Arab influence in Brumanna coming to a good school. Manor House was more the expats sending their children to that school. So I was now part of a slightly different community. And they were there, why they were there was because their mothers had told them to keep failing their exams. So they would avoid Jordanian conscription in the army. You know, it's a mother's thing, right? So there they were driving cars and all sorts of things, looking at this thing, what is going on here? So they were, I would say, the wealthier Palestinians who had left early on and had diversified assets and things. One of them, still a good friend of mine, lives in the USA now. Brother is a senior medical consultant, in Kuwait. So, both from Gaza.

AM

So, by this time you're sort of specialising in one or two subjects. Were you taking things like A-levels?

SV

So I had my GCSEs and things, or GCEs as they were at that time. And I came to UK and finished off my A-levels in London, just doing economics basically. And taking much more interest by this time.

AM

At a sort of finishing college?

SV

What is it called? London School of something. It wasn't one of these big grammar schools because I was dropped in by, in a parachute if you will, into the system here. So I went where a lot of the international students were going, I can't remember the name, somewhere in Bayswater. Did my economics, was okay. And then I don't think I had that much of a tolerance for the academic side of things. So I went off and did business studies. I did it part-time so I could work as well.

AM

And at Cranfield?

SV

No, I went to Cranfield in the end, but initially to good old Poly. Hendon to begin with, and then Middlesex as they were then. I did quite well in those places, so it was obviously that wasn't the issue for me. It was just what I wanted to do. I was always quite active, so I ended up running the motor-sports club in the college, made and sold candles, tried my hand at minicab driving for a few evenings. All these new novel things that I hadn't experienced or understood before having grown up at home in Lebanon and all that. Suddenly London was this explosion of activity that happened around me. We lived in Golders Green, so I was in and out of central London. You could park in those days on Carnaby Street, imagine that. So I was also old enough to have a driving license, so I was just absolutely everywhere finding my way around. My interest in motor-sport as well had grown because of the big boys in Beirut. So I went off to find out about all of that.

AM

This is post-Beatles, but it's still Carnaby Street.

SV

Oh my God, it was fantastic.

AM 60s, before that.

SV

We came to London in 1969. I just caught up in that anti-war sentiment. Daniel the Red in Paris and so on, and the riots in London. Grosvenor Square, was it?

AM

Yes, Grosvenor Square. I was there.

SV

You were there?

AM

Yes.

SV

So all of this was happening around me, and I could not get my head around it fully, actually. It was quite an explosion of activity. It was fantastic. So I worked at Mobil Oil for a bit, one of their marketing departments, while doing my diploma studies. Then I went off to do management studies, and I started working in the three-day week right after that, in the early 70s. I remember going to work and having a kerosene lamp on my desk, wearing coats and gloves and so on, whilst working in a small engineering company in King's Cross.

AM

That was about 1973, wasn't it?

SV

Yes, that's right, 1973.

AM

Coal miners' strikes and so on.

SV

Yes. I mean, just as an example of the kind of wilder things that happened was that my mum went on a concert tour all the way down to Italy. She and some friends that had just set off in a Land Rover with her instrument and so on. And so the house was left to me. So I decided to, aided and abetted by the skill of a friend of mine, to try and make candles and sell them. So I had three or four rounds of these, and I sold the candles in the restaurants in Hampstead. They were slightly upmarket candles and went down very well. The fourth occasion, however, I nearly set fire to the kitchen by forgetting that I had the candles on because I was busy watching something on television. So at that point, I decided that was it. So my candle-making business came to an end on that. And with motor-sport, I got involved eventually through the 80s with something called the Himalayan Rally. But in 1973-74, things were happening. In 1974, somebody I knew in Lebanon, who was also my age, came to the UK to study because our fathers knew each other. So we were young 20-year-olds by this point, and we started going out and eventually got married as well. So she's now a professor of microbial immunology at King's College in London. And her lab, Annapurna, her lab is in India, so she travels back and forth doing work on it.

AM

You're still married?

SV

Oh yes. Yes, yes, yes.

AM

That's great. Again, I hope you don't mind my asking, but you mentioned your father suffered obvious discrimination on the voyage there. And I read a number of accounts of England in the 50s and 60s when I was there. Did you face any discrimination in your early time in London?

SV

Not on the streets. There were odd things. I had a Saturday job for a time, as you do, and the manager of the shop, Sid Corb, decided that Shailendra, or Shai was too long a name, and that I should be called Charlie. And I said, but my name is Shailendra. He said, do you want the job or not? So that kind of stuff. But the hurling of abuse in my direction, only, I think it might have been once or twice, I just ignored that nonsense. Most recently it was just about lock-down time actually in Bristol, strangely enough, yes. But he was drunk and probably high and again to be ignored. I think there are other forms of discrimination which is being overlooked for promotions and jobs and things. That's way too subtle to pinpoint.

AM

Yes, yes. So at the end of the diploma, what did you decide to do?

SV

I then worked for a few years at an engineering company and then with another, two engineering companies. One was a Victorian old firm called London Shafting and Pulley, which changed the name to LSP Engineers, manufactured conveyors. They took on a Dutch conveyor belt manufacturer, became a Dutch company. So I worked with them for a bit. And then I worked for a German company which was established and based out of Essex, that made drive belts. And in fact, there's another odd connection. That company is called Optibelt. And it turns out that a member of King's, Herman Hauser's grandfather, I think, was a distributor for Optibelt in Austria. And there was I with Optibelt decades later.

AM

That's interesting. Herman's from Austria and came over from Austria. So the family had been here before, obviously.

SV

Yes.

AM

Interesting. I mean, you're trained in business. What do you do in a conveyor belt business? You can't be engineering or anything like that.

SV

So my role there was to ensure that all the supplies came into the company. And because of three-day weeks and all the oil crises and all the rest of it, trying to get all the various components in to manufacture conveyors. So that was the essence. It was a smallish firm, about 100 of us. And it was great fun. I was young and learning so much. So that was a deep dive into one firm. Because it was small enough, I got involved in a number of different things. Later on, I got involved in sales. So that was doing one thing with a lot of products. This was a lot of different things with one company. And then I went to do an MBA at Cranfield. It was '82, 82-83. Our son had just been born in '82.

AM

You've got one child?

SV

Two. And so the second one came in '91. And Cranfield, having done the MBA, it was a full time. In the 80s, Cranfield was one of the top three schools. It was good to get into that, London Business School, Manchester and Cranfield before the Judge and Said came up. But at the end of the MBA, I kind of wondered why I had done the MBA. Because all it seemed to me was about somehow increasing one's income potential.

AM

I'd like you to expand on that because I have a deep scepticism about MBAs.

SV

I think I learned a lot during that one year. It was an intense period. I learned a huge amount about both myself and about the world of business and management, more precisely. So things like operations and marketing and policy and strategy and so on and so forth. There's a huge number of things and organization development. So a lot of the frameworks that we use, I mean, they grandly call them theories in management, basically they're frameworks. And typically an MBA challenges you to reflect on your ability to think and your motivations as well. And you make some good friends from it and some good contact connections, etc. So all of that's a positive side. The other side of it is it's entirely predicated on one kind of model of economics, the free market capitalist model. And you've got no other scope for other ways of thinking about it.

AM

Rational actors promoting their self-interest and all that stuff.

SV

So 1977 was Milton Friedman's major piece of work. As that took root, everybody was into free market economics and nothing else worked. So it's really drumming that in. And being the son of an Indian diplomat slash bureaucrat, I was born into a family that grew up in the Indian way of thinking about things post-war, post-independence, which is much more of a socialist way of thinking. And certainly the legacy of our ancestors and of my parents, perhaps more strongly my father's, was about what's my purpose? Why am I here? What's the point of it all? And this is where this are so many incidents over time, people I've met, people to talk to, stories, anecdotes around me, family, friends, etc. It was commonly dominated by this notion of trying to make a difference. In that context, I couldn’t see what I had got out of this thing. So I ended up doing a PhD on the social relevance of management education.

AM

Social relevance of?

SV

Management education.

AM

Interesting.

SV

So I went down the usual route, economics, value for money and that kind of stuff.

AM

Was this at Cranfield?

SV

At Cranfield, yes. The excellent supervisor, Malcolm Harper, Oxford and Harvard and then family business, etc. He did his PhD in Nairobi on small business and entrepreneurship.

So in that case, you turn the handle to the right and you get a kind of value for money argument. You turn the handle to the left, economics, Latin American economists and so on that I read extensively at that time. I think, I don't know if I can answer anything with this. So I abandoned both after about a year and went off to read George Kelly's work in psychology, construct theory. I thought how people construe the world probably influences their behaviour eventually. It's been shown by Bandura and others subsequently. And so that was a really wonderful, insightful period for me. And also...

AM

Was that part of the thesis or did you abandon the thesis?

SV

No, no. I did a PhD at Cranfield. All this reading was all around, this huge amount of reading. And then I did about 120 interviews all in India, which is where the big question was because there was a huge amount of subsidy for management education in India at that time. And I thought, well, what if the taxpayer was really very, very poor and India is subsidizing a whole bunch of middle class people to get elite education? What are they getting back for it? Not what's the MBA student getting back for it, what's society getting back for it? Anyway, so from my point of view, that gave me a sense of direction. So then I decided to work in the world of entrepreneurship, taking all these grand management concepts that I'd learned for a year, and that I'd previously experienced as well, saying how do I apply that to people who are trying to start companies? So the kind of philosophy was not about how to make the rich more rich through all the sophisticated management tools, but how to make the poor less poor by applying some of these principles.

AM

And the Grameen Bank system?

SV