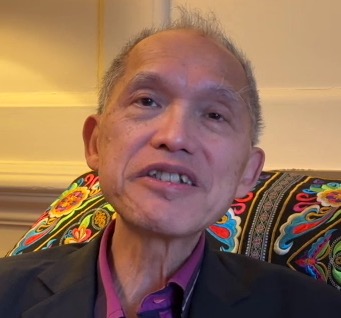

Stanley Wong

Duration: 1 hour 58 mins

Share this media item:

Embed this media item:

Embed this media item:

About this item

| Description: | Interviewed by Alan Macfarlane on 5th December 2023 and edited by Sarah Harrison |

|---|

| Created: | 2023-12-19 10:50 |

|---|---|

| Collection: | Film Interviews with Leading Thinkers |

| Publisher: | University of Cambridge |

| Copyright: | Prof Alan Macfarlane |

| Language: | eng (English) |

Transcript

Transcript:

Interview of Stanley Wong by Alan Macfarlane, 5th December 2023

AM

So it's a great pleasure and privilege to have a chance to talk to Stanley Wong. Stanley, I always start by asking when and where were you born?

SW

I was born in 1956 in Hong Kong to Chinese parents. My parents came from Guangzhou in China to Hong Kong in 1951. I remember a single thing, I mean my father, so I'm very proud of that fact. He told us he came on the day in 1951 with only the day's papers in his hands. And then he started, he used to be a shoemaker in Guangzhou, so he started a factory. Very typical in those days, a home factory making shoes. He had several, I've forgotten exactly how many, sorts of disciples, people learning the trade under him.

AM

Apprentices.

SW

Yes. And then he had also his siblings, my uncles and aunties, working together.

AM

Why did they leave China?

SW

It's mainly because of economic reasons, because it's very poor in those days in Guangzhou. And then I think by the time he left, the economy was so bad that he couldn't survive. So he was told that there's more opportunity in Hong Kong, so he came.

AM

Do you know anything about your relatives before that? Do you know about his parents?

SW

Yes, my grandparents, my grandfather, how do I describe it? In Chinese it's called the rich second generation, but it's kind of very ironic. I was told that my grandfather's father was the gang leader of the beggars in Guangzhou. So, in fact, beggars in a gang became quite well-to-do, not actually rich. So my grandfather didn't have to do anything, so he just sat there and enjoyed life.

AM

And so he was quite rich, but his son was not so rich, he was second generation.

SW

Yes, it's the effects of the wars and of the general turmoil of the time, I suppose.

AM

So your father lived through the Japanese invasion and so on?

SW

Yes, in Guangzhou.

AM

Did he ever talk about that?

SW

No, perhaps it's so bitter.

AM

Interesting. And what about your mother?

SW

My mother, again, very typical. She worked in a garden. Her father was a sort of florist, growing marketable flowers, so he worked in the fields. I think she married my father when she was hardly 18, quite common in those days.

AM

So they married in China?

SW

Yes, in Guangzhou. And then they both came to Hong Kong. So my mother worked in the kitchen in the home factory, feeding a lot of mouths, including ourselves. So what I remember, very early days, the very poor situation, there was hardly enough to eat every day.

AM

In Hong Kong?

SW

Yes, in the early 50s. We had five, I think. I have four other siblings, my elder brother, my elder sister, myself and two younger brothers. Different, born different times, of course, but we all lived together in a very typical old building on Shanghai Street. Three storeys, we lived on the top floor. Ten families, more or less.

AM

So you all lived in one or two rooms?

SW

We were lucky because we had a balcony, sort of all windows, fronting Shanghai Street. So we had a lot of natural light, but not the other families, they sort of lived inside of the apartment. And we had just one kitchen, which doubled up as the toilet. And no flushing toilet in those days.

AM

And this was for your family or for all the families?

SW

For all of them. So we got to share the kitchen and gave rise to some quarrels. So different, I mean, everybody's got to share everything else, including water supply.

AM

You said that people were very hungry. Do you remember being hungry?

SW

Yes. Yes. Because we had, I mean, my mother had to feed about 10 people in a meal. So what she got from the market, that's it. Rice in those days was plentiful, but not the other foodstuff. Vegetable and fish also good, but not meat. Chicken, strangely, in those days, considered to be a very valuable thing. So we seldom had, perhaps not even once a month, we had chicken or let alone beef. Very seldom, sometimes pork, but mostly vegetable and fish.

AM

How big was Hong Kong then? I mean, the population of Hong Kong.

SW

In the 60s, we started with, I mean, the early 60s, we started with about 3 million people.

AM

That big?

SW

Apparently boosted by the emigration from China, the very poor days of the Great Leap Forward and famine and so on.

AM

What is your first memory of your childhood?

SW

Looking out of the window from my apartment, so to speak, across the street, Shanghai Street, to the other apartments across the street. That was, I think, one of the very early memories. Not a very sunny day.

AM

So when did you first go to school and where?

SW

We call it kindergarten. Well, strangely enough, it's an Anglican church called All Saints. They operated a secondary and primary school as well as a kindergarten. So I think I went there at the age of three, about 10 minutes walk from where we lived.

AM

And was it an English medium school?

SW

No, not the kindergarten. But I think they started teaching English from primary school.

AM

So it's Cantonese?

SWS

Yes, Cantonese mainly. I remember I started off learning the alphabet. And with this typical textbook, I think widely used in Southeast Asia, in the British colonies, Malaysia, for example, Singapore. I think later on I found that out. I mean, we all had the same textbook, learning English as a second language.

AM

Did you enjoy that first kindergarten?

SW

Very vague memories. I sort of... I've lost it now. I used to have one photograph of the class with the teacher. Apparently, I mean, still very hard days. All Saints Church, I think in those days, again, very common. They dish out, what do you call it? I think I later on I found out it's sort of milk powder diluted with water. So they gave that alongside with crackers. So I remember after kindergarten, in fact, I was sort of six years old. Well, in those days, they didn't have any sort of discipline about children not wandering in the streets. We wandered about with the neighbouring children and then learnt that they have these goodies. So we went there. I remember that very vividly.

AM

Was it safe?

SW

Yes.

AM

So moving on to your next school, was it again the church school?

SW

The same All Saints Primary School from primary one to five. We had at the end of primary six, some sort of exam, a public exam, and had to take three subjects, English, Chinese and mathematics. By year five, I failed in all of them. So my teacher, in fact, well, not me, I think they told my parents that, to put it very bluntly, your son is no longer wanted. So kicked me out. So apparently my parents must have spent a lot of guanxi and time and effort to find me another school. It was across the railway line because All Saints is on the southern side, and across the street is another sort of Taiwan background, less known school. So they accepted me. So I repeated primary five.

AM

And passed?

SW

And that school, interestingly, had two very good teachers, one English, one Chinese. I mean, teaching English and teaching Chinese. So perhaps I failed very miserably and then was scolded, and made up my mind. I mean, you've got to do good this time, second time around, you won't have a third chance. So I then took the exam after primary six. Got not top grades. I think the top mark was grade one. I have two sort of very good friends, still friends today, in the same class. One made all three ones. He's now a very famous, well perhaps, a retired entrepreneur in the United States, in the Silicon Valley. He got all three ones. The other classmate, still in Hong Kong, one, one, two. I got all threes. Sorry, all twos in three of the subjects. So I was assigned to a secondary school. Another sort of, not Anglican, but sort of local Hong Kong, what do you call it? Adaptation of the Anglican church in Hong Kong called Church of Christ in China. A school called Ying Wa College, Ying meaning English, Hua meaning Chinese. So the Reverend Morrison started that in 1818 in Malacca and then moved the college to Hong Kong, 1843, I think a year after the British came to Hong Kong. And then I went to that school in 1969, started secondary one, and then went all the way to secondary seven.

AM

Were things beginning to improve economically by then in Hong Kong?

SW

In the early 70s, still quite bad. Up to about '73, the oil crisis was still quite bad. But then began to pick up afterwards, and getting better and better towards the end of the 70s. I think the Hong Kong's economy started to take off in the 80s.

AM

One of the little tigers or dragons. Were there any hobbies or interests you had in those early days?

SW

That is a decisive deciding factor. Converting to Christianity. In 1971, I was baptized.

AM

Your baptism certificate. You can hold it up. There, a little higher.

SW

Right. I forgot to show some of these documents. This is my vaccination certificate. I was barely two weeks old. And then this is one of my earliest pictures with my grandma, coming or going back to Guangzhou from Hong Kong. They had to issue a re-entry permit. I was two years old.

AM

So you were 15 or something when you converted?

SW

I met through my elder sister, an American missionary called William Reid from Michigan. He came to Hong Kong to teach English and then started making contact with his students that way, and on the streets, trying to give them the gospel. I happened to know him through my sister, and then went to church in his home, in fact. And then started learning the Bible and English. Because he only spoke English.

AM

So has that been important since then?

SW

Yes. It made, as the Bible says, a new man. It's a different perspective altogether. To everything. To family, to life.

AM

Tell me what the different perspective was.

SW

We used to be very ignorant about how life came about. What family is for and so on. Naturally, the thinking was trying to make the most money, as much as possible, as quickly as possible. That is still true today. I mean, the ethos in Hong Kong. But then the teachings of the Bible changed all that. So you don't live by bread alone. And then there is a spiritual side to life. And of course, the afterlife and eternal life. I mean, it's a total reverse of my own thinking at the time. So it's quite life-changing.

AM

And it's still very important for you?

SW

Yes.

AM

So at school, in your secondary school, were there any subjects you particularly liked or were good at?

SW

In the first three years, they call Form 1, Form 2, Form 3, we got to do quite a lot of subjects. I was quite attracted to the literal side. English, Chinese, history. Some of these more attractive subjects to me. Reading books. But not the same for science subjects. I remember the first lesson, chemistry. So the teacher was writing all of these, what do you call it, periodic table symbols on the blackboard. I simply lost interest and couldn't figure out, in the physics lesson, for example, what the teacher was talking about, there's simply no clue. So I lost interest very quickly. And at the end of Form 3, I failed almost all of these science subjects except biology. So at the end of Form 3... again, this is another turn, an important life deciding factor came along in the form of a Mr. Rex King. King's College, King. He came to be the new headmaster. The old one retired. And he came from New Zealand, perhaps from a new world. I'm not sure. He had a new way of doing things. He allowed all the students at the end of Form 3 to choose their majors for Form 4 and 5, leading to GCSEs, called school certificate exam in Hong Kong. I did quite well at the end of Form 3. We had about 160 students in four classes. I came seventh, mainly because of my English and Chinese grades, not the science. So in those days, I think still true today, students doing well, especially boys, would be expected to choose the science stream in Hong Kong. But I gave everybody a surprise. So Mr. King called us one by one by our ranking, so I was the seventh to stand up. All the six before me, of course they chose to do the science stream. I said arts. And more than that, there are two classes in Form 4 arts. Arts 1 would be doing the English literature selective. So I chose that, and that gave quite a surprise to the rest of my classmates. And then there was a great round of applause. No doubt, I thought, perhaps they think that they now have one more place in the science stream for them, because it cuts off at about 80. So if you came from the 80th place onwards, you won't be able to go into the science stream. So that was quite decisive. And then I carried on to do very well in GCSEs or the equivalent at A levels. I got a total of eight grade A's, five, yes, five in GCSEs. We did a total of eight subjects. I got five A's, one B and two E's, sorry, two D's. And then all straight A's in the A levels. I did English literature, history and economic and public affairs A levels.

AM

So you did very well. And so that took you on to university?

SW

Yes. Well, before that, I'd like to mention another very special, unique experience. Now, school certificate exam results, the announcement date. As expected, I got very good grades. So perhaps Mr. King also expected this, that I would go on to do A level English literature. I was the only one who got an A in the class. There were about a dozen or so classmates doing the same subject A levels with me. So I went into his office and, well, he knew, of course, the results. And I told him, not to his surprise, I'd like to carry on A levels English literature and other subjects. And then he just picked up the phone, called the next school, the school not next door, across the street, called Maryknoll Convent School, a Catholic school. And the principal there, called Sister Agnes McKeirnan, picked up the phone. I was there in the room. And to my surprise, I don't think they sort of rehearsed that before, Sister Agnes agreed without a second thought. OK. So Mr. King put down the phone and told me that. And then I was so thrilled. Now, about 25 years later, I wrote a poem about this incident. I can show you, or in fact, I can give you a copy of my little poem. The great memory of that day. And that, again, is another sort of deciding factor, because I went on to University of Hong Kong to do English literature.

AM

This is the English University of Hong Kong?

SW

Yes. So I picked on an Oxford poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins, a Catholic. In fact, at A-levels, I started learning about him. The teacher at Maryknoll, Sister Jeanne, was in her 70s, I think, in those days. She lived to be 104, by the way. She retired and went back to America. I didn't have time to visit her before she left. But then my wife and I went to visit Sister Jeanne about 10 years ago at Maryknoll in New York.

AM

So you went on to read English at Hong Kong University. And this is in the...

SW

1976.

AM

Did you enjoy university?

SW

Now, two things come to mind. One is the very big events in China. We were very open. I mean, Hong Kong, we had access to international news. And 1976 was a momentous year in China. I think in July of that year, there was this earthquake in China, Tangshan. And that, of course, in the tradition, Feng Shui, that would...

AM

Tell you something is going to happen.

SW

Yes, something great is going to happen, no doubt. And then I think in April or in February [January], Zhou Enlai died.

AM

Zhou Enlai or Chairman Mao?

SW

I think Chairman Mao died in September.

AM

All right.

SW

Yeah, I think Zhou in February or April. And then in April, of course, this famous... I think April 21st, [4-5th] some sort of signs were displayed in Tiananmen Square by certain people who tried to ask the people to remember how good Zhou was in the Cultural Revolution and so on and so on. And then that, well, of course, after the event, we learned that even in those days, the Gang of Four were beginning to operate after Zhou died. And then, of course, it's all history now, leading to the Chairman's death in September, and then the arrest of the Gang [Oct 1976] and so on. We all watched on TV in Hong Kong...the trial of the Gang of Four [Nov 1980], Jiang Qing particularly.

AM

What was the attitude of your fellow students towards mainland China at that point?

SW

We had... No, I forgot to mention the other point. I said two. The other is the student movement, so to speak. I think our perspective is more international because we were influenced quite a bit by the Western idea of democracy and equality and so on and so forth. So we looked at the Communist Party in China under Chairman Mao with some dismay. And then after the arrest of the Gang of Four, we thought that that would be the beginning of a change. And of course, later on, we found out when Deng Xiaoping returned to power, and that was it. A change in the whole outlook. I don't think I was alone. I mean, we were the like-minded students. We began to read a lot about the history of the Communist Party, for example, Chairman Mao's thoughts. And Deng Xiaoping's writings, particularly the clash between the philosophy of making sure that the economy works. That is the first priority. The famous saying, a cat is a good cat, irrespective of its colour, whether they can catch the mouse. So that went very deep into our heads because that was what Hong Kong was doing. I mean, we never mind the philosophy or the whatever, the teachings and so on. I mean, we've got to make ends meet and feed. In the 70s, I think we were coming up close to 4 million people, to give them housing, to feed people and so on. We were, I still remember, I mean, there was quite a lot of poverty still. Squatter huts on rooftops, on the hillsides, and a lot of fires. Although by the early 70s, the Governor, [Murray] MacLehose started in 1972, I think, a huge 10-year development program. New towns, public housing, were beginning to show the impact by the end of the 70s. The housing improvement, more variety in the market of the foodstuffs, particularly fresh fruits, international. I remember in those days, it's very rare, but a very good treat. We can get ‘Sunkist Oranges’ from California. It was very, well, we didn't have... I mean, the oranges in China, for example, are a different type, but not as good as the California ones. So then we were beginning to taste some of the fruits of the 70s. Alongside with my family, my father started moving away from the factory production into retail, setting up two retail shops, selling shoes. So our family sort of gradually improved their standard of living.

AM

Did you feel, and your friends, feel Chinese? Or did you feel somehow that you were separate by then?

SW

The identity is very interesting. We've been told that we are Chinese, and there's no difficulty acknowledging that, because we are Chinese. But every day we come across a lot of different people. I mean, there's still quite a number of British people, for example, at school. We still had a large number of English teachers at Ying Wa, and of course, Maryknoll, and in society.. the Police force, for example, still a lot of police officers, English or British. There's lawyers, courts, and even sometimes at immigration, and border checks. I mean, you see, we call them “gweilo”. The outlook is very mixed. So we were asking ourselves, I mean, Chinese, not Chinese, still undefined. Perhaps we're still too young to give very meaningful definitions to such a big question.

AM

You said, when we were talking, that it was still quite a corrupt place, police force and so on. Can you elaborate on that a little?

SW

The 60s and the early 70s were very bad. Because it's, well, even wide-ranging, I mean, at street level, not just the police officers, but anybody in uniform. They just...okay, they walk past you, and then if you are selling newspapers, you're selling whatever, then it's expected that they can pick up anything and go without paying. And that's the norm. And if you have to do anything with any government department, then you have to have some sort of “laisee”, we call that lucky money, ready. And then that would open the door or give you the position in the queue, perhaps a little better. That sort of thing. So it's very wide-ranging corruption. Well, we were sort of street level still, so we didn't know what was happening above.

AM

But do you think higher up also, there was a lot of corruption?

SW

Yes, no doubt. Because later on, I think it's shortly before 1974, when the ICC, Independent Commission Against Corruption was established, that some high-ranking police officers were arrested, and some absconded before their arrest. And we learned that... it's not just the low level. So, well, we were kind of helpless. I mean, we accepted that that was perhaps how things were done. But then the ICC started to do a lot of public education, that it is not what you should accept. And life should not be this way. And government should respect the law as well. And the law is that everybody is equal before the law. So when you're in a queue, then you're in a queue. So nobody jumps the queue. So we started to learn about these things. And no doubt, I think many of the government departments started to practice that as well.

AM

So now it's fairly uncorrupt, is it, in that way?

SW

Yes, because I worked in... perhaps we'll have time to talk about that later on. I worked in the police force for a while. I worked in the prison department for a while. A lot of other government departments.

AM

We'll have to talk about that. Yes.

SW

It's basically non-existent now. Because it's... I think two things have worked from the late 70s till now. It's the procedures, the transparencies. So when the members of the public, for example, getting a driving license, you know how it operates. It's very transparent. So you go there, you can post in an application, and it says that you will get your license back in 10 days' time or whatever it is. Or you go and line up in the transport department licensing office, and you see 20 people ahead of you, that's too bad, as they close at five. Then you're too late, so you come the next day. You can't just give a “laisee” and get in the queue any more.

AM

I think you mentioned that also at that time, and possibly still, there was organized crime. There were triads. Can you tell me something about that?

SW

That's very similar. It's kind of like cat and mouse. So they think they have to rely one on the other. So it's still there. The cat's still there, the mouse's still there.

AM

The cat is the police?

SW

Yeah, or the ICC or the law enforcement or the prison officer. Even in the prisons, we know who is the “big brother”. We check all of their history before or on reception. When the court sentences somebody to prison, then on the first day we had all of their dossier. So we know exactly who it is. So we have our own way of dealing with these people. Basically, it's separation. So we separate him from the rest of his gang in the same prison, or put them in different prisons. We separate him from the other bosses of the different gangs. You can't put them together in the same workshop. So still, they're very much alive.

AM

Interesting. So how did you do at university?

SW

Not too bad. I was aiming at a first, to be very frank. Failed. Got a two first.

AM

Two one?

SW

Yes, I did. Well, we had to do eight papers. So I did four English literature and four comparative literature, which means doing English translated works of European and some Japanese or Asian texts. And one paper on the sort of latest thinking at the time, structuralism. It was quite big in the 70s.

AM

I remember.

SW

So we did again English translation of the reader, the Ferdinand [de Saussure] social linguistics based, and so on. I think that was very fascinating and added another dimension to the traditional analysis of Shakespeare, for example. And then Gerard Manley Hopkins, I mentioned, the very wide, well, eyes wide, the very technical bit... sprung rhythm. Yes with the insight. So, perhaps more about that some later occasion. Because of that, I think I won two prizes. One Shakespeare prize and one Bank of America English literature research prize, doing Gerard Manley Hopkins. Those two are my favourite poets.

AM

In some ways to me it's strange that someone sitting in Hong Kong should find an Irish Catholic poet so much to their heart. But he obviously did affect you.

SW

Yes. Well, is this, what do you call it, inscape?

AM

Yes, inscape. [concepts about individuality & uniqueness]

SW

Yes, so it's so new. It's so fresh. The first big work we did with Sister Agnes Todd was The Wreck of the Deutschland. It's so hard, what do you call it, strong, “wrung”?

AM

Yes, I knew it very well. I did A level Gerard Manley Hopkins too. I love his poetry. So, you didn't do as well as you hoped, but it was good enough to do what when you finished?

SW

Well, it's again later on, I started looking back. And the thing is, my friends told me, I wasn't aware at the time. By the third year, we stayed in a hall of residence called Ricci Hall, the the Jesuits' hall of residence called Ricci, after Matteo Ricci, the Jesuit. And they were very famous for their activity, sports, particularly. So in the first two years, perhaps I didn't spend enough time on the whole life. So they encouraged me. I mean, you're here, you're part of our family, why not? You're sort of not being sort of in the group enough. So perhaps I was spending too much time on Shakespeare and the other things. So I decided to change a bit. Picking up, well, in fact, I'd been doing a lot of sports in earlier days. Distance, long distance running, for example, stopped that. And I started doing hockey and the rest in my final year. So you can imagine the result of spending more time in the fields. So perhaps that affected a bit the exams. I didn't realize that at the time. I thought that I could manage both. But apparently not. I didn't regret it, though.

AM

So what kind of jobs were open to you once you'd finished your degree?

SW

That again, perhaps is related to this final year change. The first one was my preference, doing a master's in the United States, because I got a Bank of America scholarship for Gerard Manley Hopkins. So I'd like to continue in America. So I wrote the applications and so on. But in those days, we weren't sort of... My family couldn't support me to that extent because it's quite expensive. So in the end, it didn't work out. At the same time, I'd applied to do the job called an administrative officer in the civil service.

AM

Governing Hong Kong [shown booklet title]

SW

That is a sort of definitive work by somebody from Oxford. I don't know him.

****AM

I know him. He's always on television. He's being very anti-Chinese. CUT OUT ALL YOUR REFS TO PATTEN

SW

So that was his work on how the administrative officer was involved in governing Hong Kong until 1997. Anyway, I read, not at the time, but I read the advertisement, that if you are bright and so on and so you have a heart for Hong Kong, then go for it. So I did. And then the third thing that is a kind of a safety valve. I applied to be an executive trainee in Cathay Pacific. I remember now my first aim, America didn't work out. The second one, administrative officer, didn't work out first time. I tried in 1979, the year of graduation, and it didn't work out. The Cathay Pacific, I also remember very vividly, it didn't work out. So I didn't work in of these. Why? Well, perhaps again, lack of experience and perhaps too honest. Was there such a thing as being too honest? I don't know. Later on, I found out that if you are interviewing for a job and if you are asked for a third interview, that means they'd like to hire you. I didn't realize that. At the end of the third interview for Cathay Pacific, I still remember somebody called Linus Cheung, who later on went on to be the CEO of Cathay. He asked me, if we offer you the job today, would you take it? So I honestly replied, no, because my first preference was still America. My second choice is doing this job. This is more or less a sort of backup. So he said, thank you. And then that's it. So I didn't have any job. Come September, a week passed. I think it was the Sunday or the first or the second Monday in September, 1979, I'm not sure. I got a call because I was sort of doing nothing at home. No job, although with a degree. In those days, a degree was quite meaningful in getting a job. Somebody from the Appointment Service, University of Hong Kong called. There was a teaching post in Tai Po in the New Territories. In those days, about 45 minutes train ride, quite far away, 25 miles from town. He said, would you like to take it? So again, without hesitation, I said yes, because I've got nothing to do. So I went there to teach English for a year. And then, of course, I believe in Providence. He made it. I met my wife there. During that year.

AM

Was she teaching there?

SW

Music. And so marriages are made in heaven.

AM

So you married there?

SW

Married 1983.

AM

And did the year go well?

SW

Not too bad, but I had no experience teaching. And then I was teaching mainly.. They had two streams, one Chinese stream of sort of English standard poorer kids. The other English stream, I was teaching Form One Chinese stream, or called middle one. You can imagine, some of them couldn't actually do the alphabet. So very hard times trying to teach them English. You're not allowed to use Cantonese. Also, I don't know how to teach English in Cantonese. So quite bad. I mean, not too easy.

AM

And then what happened?

SW

I attempted the government administrative officer. I had learnt the trick now, or perhaps that's not the word to use, to do the interviews and the exams again. And then I was asked this question again, I mean, if we offer you the job, would you take it? Of course I said yes this time. So I got it. This was in 1980. I stepped into the government secretariat and then started my 37 years in the civil service.

AM

You've been there 37... Was it the police and the prisons, that was part of the civil service?

SW

Yes.

AM

I see. How different do you think the civil service in Hong Kong, when you joined it, was from the civil service, as far as you knew or know now, of England and the homeland?

SW

Several major points. I think one is the composition. The word is localization. When I joined in 1980, as I said earlier, a lot of the more senior positions were occupied by British or English civil service people. And of course, the top ranks, the Governor, the secretaries of the policy bureaus and so on, so British. Towards the mid 80s, when the British started to negotiate the future with China, then the localization began to pick up. So we started to see a lot more local, Chinese senior people in the ranks. So that's the first one. The other is the rule base, I mentioned. In the early days, I mean, there were rule books but they were not very user-friendly. So you don't actually see them in practice. And what was in practice is the sort of guanxi and a lot of little sweeteners...

AM

Even when you joined, it was like that?

SW

No, no, I mean in the early days. In the early 70s, mid 70s, before the ICC. When I joined in 1980, the ICC has been in existence for some time. And the rules were beginning to be translated or being made user friendly. So the frontline government civil servants, they knew, they were taught how to put them in practice. For example, a lot of use of the local language, and the forms were in Chinese as well, not just in English. So the public were able to understand better how to fill in a form, how to make an application and what to expect after making the application. What to do if you are rejected, then what sort of channel of appeal there is. And if you suspect that there is some fishy business going on, you can call up the ICC and they can investigate, and so on. So even in the early 80s, it was beginning to come in. But then history is a very interesting thing. 1983, I think, started the negotiations. So that began to feature in the news a lot and began to fill up the heads of everybody in Hong Kong quite a lot. So people's attention focused on the future. What is 1997 going to bring in 15, 17 years time? And then people started talking about emigration. In fact, my parents, my family, for example, my elder brother went to Canada in 1969, not because of this, but because of the education opportunity. He couldn't get into university in Hong Kong, not doing well enough. So he started, and many family doing a similar thing, not for emigration purposes at the beginning, but then they sort of made an opening. So similarly, my family. I think my parents went with my two younger brothers in the year 1987, a few years after the negotiations started.

AM

Where did they go?

SW

Toronto in Canada. I think a lot of Hong Kong people did as well. Vancouver and Toronto. And then the economy, was sort of quite bumpy. 1987 was also the year of the first Stock Market crash following New York. So it dipped quite a bit. Well, by that time I had the opportunity of working in what we call OMELCO, quite an interesting name. It's called the Office of the Members of the Executive and Legislative Council. In those days, they called it a very strange name, “unofficial members”. I won't spend time on explaining the constitutional set-up in Hong Kong in those days, but they were the lawmakers, and the Executive Council was the Governor's cabinet, as it were. So they were not elected initially. They were the representatives of the people advising the Governor on how to govern Hong Kong. And they had meetings. And the legislative side, of course, they made laws, but they had their own in-house meeting once a week. And we were staffers. So we had the opportunity of having a meeting together. We'd take notes and follow up. So come 1987, a few days after the crash, the Hong Kong market closed for four days. It was about to reopen the next day. I remember we were at this meeting and the members were told by the senior member called Sir S.Y. Chung, a senior member of the Executive Council, like the chief advisor to the Governor. He came from the cabinet meeting, returning from Government House, and broke the news that the market was going to reopen tomorrow. And that was about three o'clock in the afternoon, the day before. And then he also said the second point was that the Government would use public money to set up a fund to back up the market, because he expected that the market after four days closure would make a big dip. So it did, and then that tied us over. This Government had forgotten exactly the amount of the government funding put into this fund to expect the crash. So those days were not too good, but I got my first promotion in 1987 from the basic rank of administrative officer to senior administrative officer.

AM

Within a year?

SW

No, I mean in seven years time, which was the norm, I think, in those days. And then I got my first sort of acting appointment to the next higher rank the following year, 1988, in the Education and Manpower Branch of the Secretariat, as it was called, mainly dealing with labour legislation. Very hard work. My first taste of lawmaking. We started with the drafting instructions to give to the lawyers, stating the policy intentions. And in fact, found out that that was very, very crucial to the process of lawmaking. So you've got to make absolutely clear what your intention is for the lawyers to translate that intention into the legal language. And then the next stage, of course, is to deal with the lawmakers. In those days, it was a lot easier, I think, because they were more reasonable and they didn't have party politics, which meant that some were better than others in understanding what the purpose was. Some might have their own agenda, but they never brought sort of party politics into it in those early days. The first set of elections to the legislature were held in the year 1985, a few years back. So bringing in the sort of people's representative, like some of the famous names before 1997, Martin Lee, for example, and others would appear more frequently legislative side

later on. They were sort of passing on the voice of the people in the legislature. So in lawmaking, I think this is a very important element. For labour legislation, it's even more important because it's all the common people working in the factories, in the construction sites. The worst situation I had to deal with was accidents, industrial accidents. Say falling from height, usually resulting in deaths, very poor, usually it's insufficient equipment and education. And then of course, in those early days, is the inadequacies of the laws. So we tried to make amends, introducing, say, a series of very intricate systems of insurance, making sure that every layer of the process in the construction industry was well insured. So in case of any accidents, at least you have some compensation. We even thought of those sort of cowboy contractors, fly-by-night, not doing any insurance. And we even thought of levying a fund from each insurance policy to set up a compensation fund for those poor workers whose employers don't buy them any insurance. So those were very, very fruitful days. I mean, I felt having done something good for Hong Kong, bringing in a very comprehensive set of labour legislation. And that brought me to, in fact, very soon afterwards, my second promotion in 1990, more or less entering into my sort of mid-career. It was a very interesting time, very, very, what's the other word? Interesting is too common. Shall I use the word unique because I was very fortunate. Well, everybody knows what happened in 1989 in June in Beijing. Soon following that, repercussions in Russia, bringing down..., I'm not sure whether there is any causal relations, leading to the breakup of the Soviet Union. And the news was broken on the wire. We used telegrams from the FCO, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, to all of the posts, including Hong Kong. And that telegram was at the time very fortunate. I was deputy to the Press Officer to the Chief Secretary, the number two in the government. The Press Secretary went on leave so I was asked to occupy his room for the time being. The room was next door to the Chief Secretary, and there was this telegram machine outside of my office. My secretary came in one evening with this blue, printed on blue paper, this telegram from the FCO saying that the Soviet Union, the USSR as we know it now, was no longer. And following that, soon following that, I'm not sure whether there is any relation, another telegram saying that we will replace the Governor. In those days, I think it was somebody called David Wilson. His successor was not named in that telegram. But we learned, and then we had to do some preparation for the PR work to sort of soften the ground for the reception of the news when the announcement was formally made soon afterwards. By 1992, we knew who was going to come, of course, when Christopher Patten came. And that started five years of very exciting times in Hong Kong. I think Patten chose the title of his first address to the legislature in Hong Kong 'Our Last Five Years'. It's called the policy address. I think it's sort of like the Queen's address to Parliament every year at the start of the legislative year. And then he laid out very ambitious plans to bring democracy and elections to Hong Kong. And then I had the fortune, or misfortune, to be the only person in his sort of inner PR group dealing with the propaganda warfare with China. You might have read about that in the news a lot in those days. Beijing would fire a salvo of all sorts in the morning in their newspapers. Well, not much television in those days, or newspapers. And then all the local newspapers would follow. And then I was amongst three, I think, of the more junior in the team, who knew both Chinese and English. So Patten would not wait until several hours later for the Chinese press to be translated into English for him to read. We were asked to do a very quick translation every day of the gist of what Beijing was sort of telling him to do, what to do, what not to do. So then he would think of the appropriate response when he stepped out of the office and being interviewed by the press. Very exciting. So all of these were very new.

AM

Do you think his policy, which was to be really confrontational with China, to show that he didn't have much regard for it, that he wasn't interested in going there, learning anything about China, do you think that was a good policy?

SW

I think to be fair to him, and of course I, like so many other people, with the benefit of hindsight, perhaps it's not exactly fair to him to comment on what I'm going to say now. I think he did what he had to do at the time. I'm not sure whether he knew at the time what reaction that would bring from Beijing. Of course, he quickly knew that that was no go. And that was to the eyes of the powers that be in Beijing, that that was a breach in trust, a breach in some of the tacit agreements made. In fact, there was part of this very intense propaganda war, there was, well not a leak, I mean intentional leak, of seven letters or seven exchanges of diplomatic exchanges to the media and it's all published in detail, detailing mainly how the new legislature, the first legislature, post-97, was going to be made, how the membership and so on and so forth in great detail, and how Patten's new blueprint announced in the policy address I mentioned, was entirely different, for example. So we can understand the frustration, as it were, on the Chinese side at the time.

AM

Do you think there was a breach of trust?

SW

It's difficult to put a gloss on. If you read those seven letters, then of course you would draw the same conclusion as everybody else who read those letters, that the trust and the agreement was breached. But then there might be more evidence that was not revealed. I'm not sure whether we could now have access to some of these papers, I'm not sure whether they are still subject to the 30 year rule

Yes. But what I was trying to say is that the impression I got, a sort of a small potato from the inside, as it were, of him, and the reaction that in Hong Kong we got from his first policy address. And then following on from that, this propaganda warfare resulted in the sort of to-ing and flowing of relationships, I mean, ups and downs, until the end of the British rule in 1997. So quite a few years of ups and downs, not just the political side, but also the social side, because a lot of the policies, perhaps he was... one worth mentioning, is the so-called retirement protection that he had a mind of introducing. It's called Mandatory Providence Fund. It's still in use today. Although it's, well some sort of academics would call it cosmetic. In truth, I think in substance, it is true. I mean it's cosmetic. But it started as the first such formal scheme of trying to protect people's retirement income in such a way. So I think to be fair, you have to have to give at least some credit to him for that as well. In truth, as I said, it doesn't make too much of a payment for somebody's retirement. But something's better than nothing.

AM

Many people in the West predicted that Hong Kong would crash. At the moment it was separate, the stock exchange would crash, that everyone would leave and there would be disaster. What difference did you notice the day after?

SW

Oh, it's typical Hong Kong. We laughed. I mean, we've seen so many of these in the past 50 , 60 years. I mean, the Cultural Revolution, even the Second World War, and so on. You know, almost every 10 years or so, we had something big. I mean, well, again, 87 seems to be a very interesting year. The same year, I think, if I remember correctly, we had something called a nuclear plant being built in Daya Bay, 50 miles or kilometers from Hong Kong. So that sort of meant the end of the world for Hong Kong for a while. Then 97 itself, of course, 10 years from 87. And then the 2008-9, you have Lehman Brothers. ...

AM

So you didn't notice much difference in 97?

SW

No, no, no, no, don't get me wrong. The change is big. So it's not as simple as what Deng said, just a change in the flag. No, it's not as simple as that. Of course, the police changed their insignia at midnight from the British coat of arms sort of emblem to the Chinese. And then of course, the flag was lowered. It's not a sudden, it's not a sort of overnight change. But I mentioned localization. I mentioned the use of Chinese. I mentioned the more widespread involvement of the public in of public affairs. People are more involved. They make a lot of complaints for someone. That in fact is a good thing. From a bureaucrat's point of view, you've got to deal with a lot of complaints every day, spending a lot of time on the files is not a good thing. But it's a good sign that people care about the place. So they don't like something happening, then they take the trouble to call or to write, and then begin to use email. So people are beginning to get involved. A lot of these were quite different before 97. I also will start on something new. When I was posted in 1999 to do financial services. That was the start of another big step of the role of Hong Kong changing after 97. In those days, the top secret, the financial secretary and myself and others on the top financial services officials started many trips to Beijing to talk with our counterparts in the Ministry of Finance, the People's Bank, and so on. Mainly trying to pave the way for monetary instruments, renminbi denominated instruments, to be introduced into Hong Kong. And then gradually, after several years, it came to fruition that new financial instruments were introduced into the market in Hong Kong, into the banking system. Gradually, then nowadays, of course, it's everybody's knowledge. You can actually trade stocks and shares in Hong Kong. And then there is some connection between the stock exchanges, Hong Kong, Shenzhen and Shanghai.

AM

What currency does Hong Kong use?

SW

Now, of course, the Hong Kong dollar has been guaranteed in the joint declaration and in the basic law. So we don't have to have other currencies. And legal tender is still the Hong Kong dollar. But for a long, long time, I think since 1994, if I'm not mistaken, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority started a very far sighted infrastructure of what they call the settlement system. You can actually... the bank system in Hong Kong can settle in three currencies, in addition to the Hong Kong dollar, the US dollar and euro for a long time now. So the way I think is now paved for one day to come when the RMB can be freely traded in Hong Kong. But I'm not sure how long.

AM

It hasn't, it isn't yet.

SW

No, no.

AM

Interesting. So you were in the finance, financial department. What was the next stage?

SW

And then the prisons. Another very interesting job. I was posted to deal with something called the Mega Prison Project. Somebody had the brilliant idea, land being so scarce in Hong Kong. We had more than 30 prisons in Hong Kong, the most famous of which is called the Stanley Prison, my namesake, in a place called Stanley at the tip of Southern Hong Kong Island, occupying a big chunk of land. And then some 30 other prisons scattered around, some on the island, some on the mainland, some elsewhere. So somebody had to brilliant idea. Why not just get rid of all of these prisons and build somewhere, one prison, good enough for all the prisoners. And then release all of this precious and valuable land for development, for other more useful purposes. So I had to deal with that. And then the public had a huge cry against the idea, because nobody likes to have a prison, let alone a mega prison near their backyard. So I had to deal with that. So I told the Commissioner of Correctional Services, (it's not called the prisons, it's called Correctional Services). Okay, why not forget about this, because you'll never get it through the Legislature. You'll never get the funding because a huge prison means huge sums of money, and then a long time to build. So it's not going to work. Why not forget about that and use it as a kind of bargaining chip with the government for a series of what I call “in situ redevelopment”. You build some. Find a good piece of land, sort of no man's land, and start a new prison. And then you can move one of the existing prisons to that, releasing that piece of land. And then you can return that to the government, and so on and so on. So you do that. And that would be, I think, piece by piece, you have a much better chance of getting through the Legislature, getting the public's approval, because it's small. You don't have upwards of 10,000 prisoners in the same place. So, in fact, that is still the policy today.

AM

That was your idea.

SW

Yes. I was there quite a few years. That was one of my ideas. The other one is improving the rations. So, I mean, rations and meals is a big thing in the prison. So we had a very good tendering system. But again, somebody sometimes said, okay, it's always this tender. Perhaps there's something fishy. I mean, upwards of, I don't know, several decades. Why is it still the same guy, the same company, gets the contract? Why not change it? That's before my time. So they changed it, but it only lasted for one day. Doesn't work because he never got the logistics. Because, I mean, 30 odd prisons scattered on all sorts of places in Hong Kong. The logistics is not easy. And to be there on time and to have the correct amount, it's not an easy job. And there is a very small margin of profit. So I had to sort of recall as an emergency measure, the old supplier. And then to buy time to do a new tender. So I restructured the way to sort of modernize the diet and modernize the specifications, and to improve the tendering procedure to make sure that it's transparent, it's fair. From time to time, there are newcomers. Some are better than the old ones. For example, rice. Rice is a very important element in the diet. A newcomer, no doubt wanting to get into it for the longer term. He pays a very good price in one of the tenders. And of course, he was awarded it because a very good price, very good quality. And then it proved to be good grain. So in those days, it's a great improvement for the rice diet. That was quite satisfying as well.

AM

You've done something useful. So what was the next?

SW

The next is my retirement posting. Again, a very unique.

AM

When was that?

SW

2009. For seven years, eight years, the Central Policy Unit, the government's think tank. We do three things, I think. One is to do the Governor's (or the Chief Executive now) policy address every year. I was the sort of editor. The other is policy research. Looking ahead of time, not duplicating what the policy bureaus were doing. The third is to administer a public policy research fund, helping the academics to do policy research. We just administer the funding. They have total freedom to choose how and what they do. So a very interesting seven years, eight years. I had the opportunity to work with three, I think three chief executives in that posting. One is Donald Tsang in 2009. From 2002, his end of office, 2012. And then CY Leung from 2012 to 2017, I think. And then only for a month, the last one, Carrie Lam, the month of July. I think she took office first of July and then I retired the end of July.

AM

So you knew her. I mean, she's the one who is best known in the West now. And there are very mixed assessments of how good or bad she was. She earned a lot of vitriolic attacks from various people. But what was your impression of how well she managed?

SW

What I'm going to say my personal, personal in both senses, from my own view, and then as a friend. I think we reported for duty as administrative officers on the same day, 1980. And then a year later, she came here, I think, to Cambridge for training. And then I went to the other place. And we were more friends than colleagues. So we seldom talked about office. But I know her husband, I know her children. And then in the last 15 years or so of our careers, we seldom had the opportunity to meet because I tayed at a certain rank in the civil service where she, of course, rose further and further. So our paths seldom met. So what I'm going to say is that my personal view of her is very, what do you call it, dedicated. She knows her stuff much, much better than all around her. Those above, those below, those in parallel. Knows in great detail about everything. So she doesn't have to look at the notes. At meetings, she's very sharp. So you pretend that you know something that she doesn't, because she always knows everything better than yourself. But as a friend, she has a very good distribution of time. She had in the early days, in the family to bring up two sons. I think, at least the first one went to college here. I think even the second son went to college here as well. So with younger children, she's got to be a mother. At work, she insisted on getting off work at a certain time, not too late, in order to go to the market, and then to go home and do what mothers do, feed the family and so on. Not very often, but sometimes our friends are of very similar vintage. We have gatherings and we had the social events. And so we're just like any of our colleagues. Those are my impressions. But of late, of course, I read the news as well. Particularly in the more difficult days about 2019 and thereafter. Very, very dark times, not just for her. I mean, for us as retired, ordinary citizens, very difficult times in Hong Kong. I had the misfortune of actually running into some of these troublemakers in black. I was attending a wedding. I lived in Hong Kong after retirement, near the railway station. I had to go to the Cross-Harbour tunnel to take the bus to the Hong Kong side to attend the wedding. At the same time, to my misfortune, two columns of black troublemakers, I call them.

AM

These are the protesters?

SW

I don't call them protesters. I call them troublemakers. Walk out of the Hong Kong railway station at the same time as me. And then they file in two columns, different directions. I didn't know at the time, but three minutes later, I knew why. One went across the footbridge to the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and went down to the other side of the Cross-Harbour tunnel. This column went to the same side as I was trying to catch the 104 bus to Hong Kong. And we met again right at the same time I was joining the queue at the bus stop. They were streaming down the stairs. Immediately, they pushed the barrier and the litter bins onto the road, stopping the buses. At the same time, the other side were doing the same thing. In fact, later on, of course, I read the news and knew that they were trying to blockade the Cross-Harbour tunnel. And they did, and then stopped the main artery of traffic in Hong Kong, at least for a few hours. I can't remember for how long. And then I had to walk. I immediately walked the other way. I had to catch the... went to the other station called Tsim Sha Tsui East to catch the MTR to go across the harbour. And that was my sort of close personal encounter with these troublemakers.

AM

What was behind... you say they're not protesters, they're troublemakers?

SW

I detected that on the surface, like the so-called Occupy Central, whatever it was, 2014. I detected that on the surface, they were saying something very beautiful. Like, I'm not sure, what were the slogans.... This is Hong Kong or this is Our Hong Kong, something like that. As if there were two or more Hong Kongs. But I think their true intentions, my own point of view at the time, because I've been with the police force. They were trained to invite or to excite the frontline police officers to use force, in particular to open fire, in order to create even more trouble. That was what I understood much later on, not at the time, because later on I didn't have the fortune, misfortune of meeting them on the street. I looked at the news on television. Some of the tactics I could recognize. I think somebody taught them, I don't know who, perhaps former police officers, because they knew under what circumstances a police officer would be allowed to draw their weapon and even open fire. So you can tell. One incident I remember watching on television news, that they surrounded one police officer and using, I don't know what, a rubbish bin or whatever to make him fall onto the ground. And then used bricks, trying to hit him on the head. I mean, these are very clear to me that these are sure tactics to the colleagues, perhaps 20 yards, 50 yards away. I think indeed, if I'm not mistaken, you can check the news, on that same incident. One police officer drew a revolver and fired one shot at the sky, not at the protesters or wherever they were. And then they scattered and helped save the colleague.

AM

If that was their tactic to try and get the police to be violent towards them, what was the longer term aim or goal of these people?

SW

I can only conjecture. I mentioned the 2014 incident and that was quite a good comparison. No such tactics were used in that. I think they blockaded Central Admiralty, Tsim Sha Tsui, and Mong Kok for two months, three months, and on the whole, rather peacefully. And then they more or less had one objective, trying to make a better Hong Kong and so on. But they were quite different tactics in 2019 and those years. So perhaps the times have changed, or some call for different tactics, or they try this one and it didn't work, so they've got to try something else.

AM

There's been speculation that there was external encouragement or training or financing, maybe from the CIA or elsewhere. Is there any evidence for that?

SW

I don't know. But it's no secret. CY Leung was the former chief executive, and at least in the 2014 incident or series of incidents, he did use external forces. He did use that term. So I don't know whether he had evidence or not. I don't.

AM

When I talked to a very senior British diplomat about this, who was in Hong Kong previously, and I put it to her that the kind of behaviour that these people were doing, shutting the metro station and the airport and going into the parliament and so on, wouldn't have been allowed for one hour in England. If this had happened in London, the police and then the army if necessary would have gone in and arrested them all. And in America. And this person said, well, that's what they should have done. It was useless policing by the Hong Kong police. What is your answer to that?

SW

I disagree. I think it's due to the very, very perceptive insight of those in control at the time. Seeing through that violence, force is not the solution. Patience, peaceful, you call it negotiation or you call it discussion, whatever it is. You take time, you ride it out. And then of course you have to have to deal with specifics. On some occasions, as I mentioned one, you had to use some warning shots, perhaps. But certainly, the police were very, very professional. I had the fortune of working with them for a short while and I know their training is second to none. And their discipline, again, is I think perhaps one of the best police forces, not only in Asia.

AM

Does that mean that now that, as it were, absorbing and then coming back approach means that Hong Kong is at peace with itself now? Has it had a long term good effect?

SW

I think there is a price to pay. Well, I've been relocated to this country for about five, six years now, so I might have lost touch. Although I return to Hong Kong from time to time, once a year. The mood is certainly different. So people on the whole can go about their business without having to allow much more time for travelling or for emergency alternatives to be made, and so on. On the other hand, of course, there are people who don't like the sort of atmosphere that you are kind of somebody who might use some of these emergency laws or whatever it is, national security laws, in the wrong way. But if you talk to people individually, as I do, I mean, I have, of course, still a lot of friends and relatives, that, to the ordinary people, is, I think, a price worth paying. That you have the, how do you call it, the peace of mind to go about your business on a day to day basis. For example, to be sure that the MTR works, that the tunnel is free, and the buses come on time, to give up, if I can use that term. That you don't make certain remarks, and you think a lot more before you post certain news or hearsay without proof on the social media. I read some of the prosecuted cases in the courts. These people perhaps are not as careful, or do due diligence to check beforehand. They perhaps made rash decisions without seriously thinking them through, and fell prey to the instant gratification, now prevalent in the social media.

AM

What is your feelings about the future of Hong Kong?

SW

I always say, since the early days of my career, Hong Kong is, how do you call it? In Cantonese is, fuk de, in Mandarin is fu xin fu. I will translate that, there is not a very satisfying translation in English. It's not fortunate. It's not fortune. It's some sort of rich endowment, perhaps. It's the meeting of people, time, and place in Hong Kong. Sort of richly endowed in all three ways. I think it's still true today.

AM

In what way is it different from Shanghai, which also is richly endowed as a meeting place of the East and the West?

SW

Let me quote you one incident, my personal experience. 2009, I went to Shanghai on an official visit. I was just posted to the correctional services, but I still remember my financial services days. In 2009, Beijing gave Shanghai a critical directive to become a financial centre for the mainland in 10 years' time. The officials that met us, the municipal officials that met us, knowing that I'd been with the financial services in Hong Kong before, told me very politely that they had a lot to learn from Hong Kong and how to accomplish what Beijing has given them, this task of becoming a financial centre in 10 years. I think they did a very good job, although of course Hong Kong, not me, but a lot of my colleagues still in the financial services, worked together and gave them some advice. Of course, they are also staffed by very brilliant people in Shanghai. I think even better people, I dare say, because they are much larger. They in fact had a much longer history of being international than Hong Kong.. If you go to Shanghai today, you will still find the architecture, for example, which is absent in Hong Kong. Even in Hong Kong's days, still very much just British. There are some Portuguese, some French as well, but not as cosmopolitan as Shanghai. So I think if you look into the future of Beijing's directive, I've lost touch, I'm not sure what the current policy is from Beijing to Shanghai.

AM

It's been reinforced because Xi Jinping has just been in Shanghai encouraging them in this direction further.

SW

In 2009, the idea was for Hong Kong to go international and for Shanghai to sort of be domestic. So I'm not sure whether that's changed.

AM

No it's changing just now. What effect did the rise of Shenzhen have on Hong Kong?

SW

Sorry?

AM

The rise of Shenzhen.

SW

Ah, that's very interesting. I was in Hong Kong two months ago. I particularly made a point of visiting Shenzhen. I have two friends living there actually, Hong Kong people, retired, who chose to live in Shenzhen. So I visited them and they showed us around. I think they leap-frogged, I think I ought to use that word. They leap-frogged a lot of the difficulties or valuable experience or mistakes that Hong Kong made, or other places made in the process of modernization. For example, the electronic payment is widely used, even more so than in Hong Kong. I mentioned over lunch, in Hong Kong, a lot of the taxi drivers, I think less than 1% would accept electronic payment. They still accept cash or they prefer to have cash. So Hong Kong still, I mean, we've got a lot to do to catch up. So Shenzhen, I think they don't have to. I think they won't look back.

AM

So you feel Hong Kong is rather old-fashioned and British?

SW

No, perhaps I ought to balance that impression a bit. I think we, from the artistic, let's go into some detail. As you know, my wife is a musician. My daughter is a sort of movement artist. She lives here. In the arts, particularly the performing arts, I think we are still very much innovative. We encourage innovation. We sort of have the opportunity for collaboration, for the mix of different art forms. Still very much alive. And I think that that's one point that going forward, Hong Kong can see.

AM

And film-making?

SW

Yes. Financial services, of course, because we think most of the big banks around the world are represented in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong dollar is still backed against the US and guaranteed in the basic law. And the renminbi is going international, although of course there's no sort of prediction as to how soon. So a lot to do for Hong Kong in this area still. And then how we try to encourage the cooperation with our neighbours, not just mainland China, what do you call it, the big bay area. There's great potential. But also our international connections. Now, Southeast Asia, for example, Japan, further afield because of our British connections with Europe and even America. Those are still very strong points going forward for Hong Kong. So I think with Shenzhen, we will find our respective niche in the big bay area. Apart from Shenzhen and Hong Kong, on the west of the Pearl River estuary, Macau is an interesting neighbour. It' has a much longer history than Hong Kong. They have found their niche. They have a very unique Portuguese culture and they have very good infrastructure for tourists and so on. A small place. But still, well, we also made a point to go there for a day trip two months ago. Still very vibrant Macau. We didn't have time to go to Zhuhai. I heard that because of the bridge, it's also developing very well. I also ought to mention the bridge. In 1995, I didn't have time to mention that I again had the good fortune of being the secretary to the Sino-British Infrastructure Coordinating Group, which started planning for the bridge, as well as other air traffic control centres in the Pearl River Delta and another sea channel from Hong Kong into Shenzhen. So it's very satisfying repeating that work. When I landed in Hong Kong five years ago when the bridge was commissioned, by then it was by the new airport, and I actually saw the bridge in which I participated in part of the planning back in 1995.

AM

Very satisfying. So you've had a very satisfying life.

SW

Yes. Excellent.

AM

Well, I'd like to thank you very much indeed for a very satisfying interview. Thank you.

SW Thank you, Alan.

AM

So it's a great pleasure and privilege to have a chance to talk to Stanley Wong. Stanley, I always start by asking when and where were you born?

SW

I was born in 1956 in Hong Kong to Chinese parents. My parents came from Guangzhou in China to Hong Kong in 1951. I remember a single thing, I mean my father, so I'm very proud of that fact. He told us he came on the day in 1951 with only the day's papers in his hands. And then he started, he used to be a shoemaker in Guangzhou, so he started a factory. Very typical in those days, a home factory making shoes. He had several, I've forgotten exactly how many, sorts of disciples, people learning the trade under him.

AM

Apprentices.

SW

Yes. And then he had also his siblings, my uncles and aunties, working together.

AM

Why did they leave China?

SW

It's mainly because of economic reasons, because it's very poor in those days in Guangzhou. And then I think by the time he left, the economy was so bad that he couldn't survive. So he was told that there's more opportunity in Hong Kong, so he came.

AM

Do you know anything about your relatives before that? Do you know about his parents?

SW

Yes, my grandparents, my grandfather, how do I describe it? In Chinese it's called the rich second generation, but it's kind of very ironic. I was told that my grandfather's father was the gang leader of the beggars in Guangzhou. So, in fact, beggars in a gang became quite well-to-do, not actually rich. So my grandfather didn't have to do anything, so he just sat there and enjoyed life.

AM

And so he was quite rich, but his son was not so rich, he was second generation.

SW

Yes, it's the effects of the wars and of the general turmoil of the time, I suppose.

AM

So your father lived through the Japanese invasion and so on?

SW

Yes, in Guangzhou.

AM

Did he ever talk about that?

SW

No, perhaps it's so bitter.

AM

Interesting. And what about your mother?

SW

My mother, again, very typical. She worked in a garden. Her father was a sort of florist, growing marketable flowers, so he worked in the fields. I think she married my father when she was hardly 18, quite common in those days.

AM

So they married in China?

SW

Yes, in Guangzhou. And then they both came to Hong Kong. So my mother worked in the kitchen in the home factory, feeding a lot of mouths, including ourselves. So what I remember, very early days, the very poor situation, there was hardly enough to eat every day.

AM

In Hong Kong?

SW

Yes, in the early 50s. We had five, I think. I have four other siblings, my elder brother, my elder sister, myself and two younger brothers. Different, born different times, of course, but we all lived together in a very typical old building on Shanghai Street. Three storeys, we lived on the top floor. Ten families, more or less.

AM

So you all lived in one or two rooms?

SW

We were lucky because we had a balcony, sort of all windows, fronting Shanghai Street. So we had a lot of natural light, but not the other families, they sort of lived inside of the apartment. And we had just one kitchen, which doubled up as the toilet. And no flushing toilet in those days.

AM

And this was for your family or for all the families?

SW

For all of them. So we got to share the kitchen and gave rise to some quarrels. So different, I mean, everybody's got to share everything else, including water supply.

AM

You said that people were very hungry. Do you remember being hungry?

SW

Yes. Yes. Because we had, I mean, my mother had to feed about 10 people in a meal. So what she got from the market, that's it. Rice in those days was plentiful, but not the other foodstuff. Vegetable and fish also good, but not meat. Chicken, strangely, in those days, considered to be a very valuable thing. So we seldom had, perhaps not even once a month, we had chicken or let alone beef. Very seldom, sometimes pork, but mostly vegetable and fish.

AM

How big was Hong Kong then? I mean, the population of Hong Kong.

SW

In the 60s, we started with, I mean, the early 60s, we started with about 3 million people.

AM

That big?

SW

Apparently boosted by the emigration from China, the very poor days of the Great Leap Forward and famine and so on.

AM

What is your first memory of your childhood?

SW

Looking out of the window from my apartment, so to speak, across the street, Shanghai Street, to the other apartments across the street. That was, I think, one of the very early memories. Not a very sunny day.

AM

So when did you first go to school and where?

SW

We call it kindergarten. Well, strangely enough, it's an Anglican church called All Saints. They operated a secondary and primary school as well as a kindergarten. So I think I went there at the age of three, about 10 minutes walk from where we lived.

AM

And was it an English medium school?

SW

No, not the kindergarten. But I think they started teaching English from primary school.

AM

So it's Cantonese?

SWS

Yes, Cantonese mainly. I remember I started off learning the alphabet. And with this typical textbook, I think widely used in Southeast Asia, in the British colonies, Malaysia, for example, Singapore. I think later on I found that out. I mean, we all had the same textbook, learning English as a second language.

AM

Did you enjoy that first kindergarten?

SW

Very vague memories. I sort of... I've lost it now. I used to have one photograph of the class with the teacher. Apparently, I mean, still very hard days. All Saints Church, I think in those days, again, very common. They dish out, what do you call it? I think I later on I found out it's sort of milk powder diluted with water. So they gave that alongside with crackers. So I remember after kindergarten, in fact, I was sort of six years old. Well, in those days, they didn't have any sort of discipline about children not wandering in the streets. We wandered about with the neighbouring children and then learnt that they have these goodies. So we went there. I remember that very vividly.

AM

Was it safe?

SW

Yes.

AM

So moving on to your next school, was it again the church school?

SW

The same All Saints Primary School from primary one to five. We had at the end of primary six, some sort of exam, a public exam, and had to take three subjects, English, Chinese and mathematics. By year five, I failed in all of them. So my teacher, in fact, well, not me, I think they told my parents that, to put it very bluntly, your son is no longer wanted. So kicked me out. So apparently my parents must have spent a lot of guanxi and time and effort to find me another school. It was across the railway line because All Saints is on the southern side, and across the street is another sort of Taiwan background, less known school. So they accepted me. So I repeated primary five.

AM

And passed?

SW

And that school, interestingly, had two very good teachers, one English, one Chinese. I mean, teaching English and teaching Chinese. So perhaps I failed very miserably and then was scolded, and made up my mind. I mean, you've got to do good this time, second time around, you won't have a third chance. So I then took the exam after primary six. Got not top grades. I think the top mark was grade one. I have two sort of very good friends, still friends today, in the same class. One made all three ones. He's now a very famous, well perhaps, a retired entrepreneur in the United States, in the Silicon Valley. He got all three ones. The other classmate, still in Hong Kong, one, one, two. I got all threes. Sorry, all twos in three of the subjects. So I was assigned to a secondary school. Another sort of, not Anglican, but sort of local Hong Kong, what do you call it? Adaptation of the Anglican church in Hong Kong called Church of Christ in China. A school called Ying Wa College, Ying meaning English, Hua meaning Chinese. So the Reverend Morrison started that in 1818 in Malacca and then moved the college to Hong Kong, 1843, I think a year after the British came to Hong Kong. And then I went to that school in 1969, started secondary one, and then went all the way to secondary seven.

AM

Were things beginning to improve economically by then in Hong Kong?

SW

In the early 70s, still quite bad. Up to about '73, the oil crisis was still quite bad. But then began to pick up afterwards, and getting better and better towards the end of the 70s. I think the Hong Kong's economy started to take off in the 80s.

AM

One of the little tigers or dragons. Were there any hobbies or interests you had in those early days?

SW

That is a decisive deciding factor. Converting to Christianity. In 1971, I was baptized.

AM

Your baptism certificate. You can hold it up. There, a little higher.

SW

Right. I forgot to show some of these documents. This is my vaccination certificate. I was barely two weeks old. And then this is one of my earliest pictures with my grandma, coming or going back to Guangzhou from Hong Kong. They had to issue a re-entry permit. I was two years old.

AM

So you were 15 or something when you converted?

SW

I met through my elder sister, an American missionary called William Reid from Michigan. He came to Hong Kong to teach English and then started making contact with his students that way, and on the streets, trying to give them the gospel. I happened to know him through my sister, and then went to church in his home, in fact. And then started learning the Bible and English. Because he only spoke English.

AM

So has that been important since then?

SW

Yes. It made, as the Bible says, a new man. It's a different perspective altogether. To everything. To family, to life.

AM

Tell me what the different perspective was.

SW