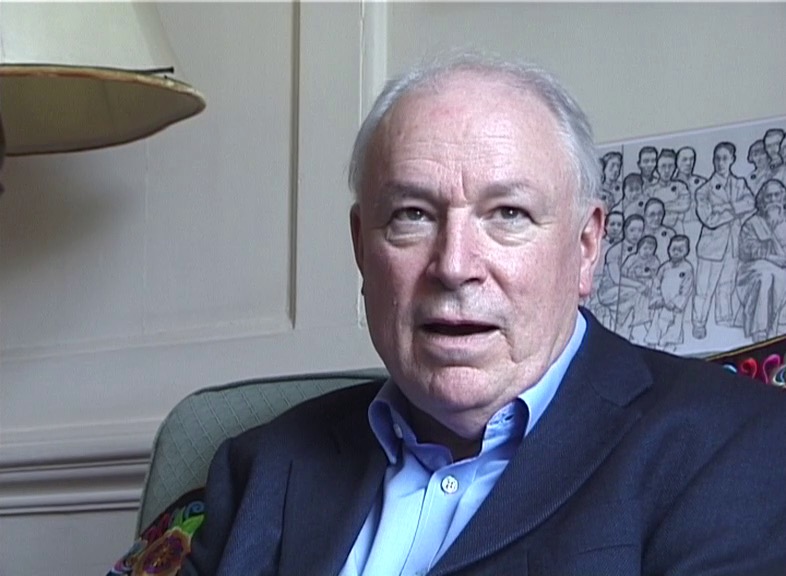

Gareth Austin - part 2

Duration: 28 mins 50 secs

Share this media item:

Embed this media item:

Embed this media item:

About this item

| Description: | An Interview of Gareth Austin on 10th May 2023 by Alan Macfarlane |

|---|

| Created: | 2023-10-23 11:01 |

|---|---|

| Collection: | Film Interviews with Leading Thinkers |

| Publisher: | University of Cambridge |

| Copyright: | Prof Alan Macfarlane |

| Language: | eng (English) |

Transcript

Transcript:

Gareth Austin 10th May 2023

[AM – Alan Macfarlane; GA – Gareth Austin]

AM: It's a very great pleasure, after many years of knowing you, Gareth, to have a chance to talk about your life and work. I'm going to start by asking when and where a person is born. GA: Thank you very much for asking me, Alan. I was born in Ibadan, Nigeria, while it was still a colony. So, in 1956, four years before Nigerian independence, and six years before my parents returned to Britain, bringing me and my sisters with them. So, my first memories are obviously of Nigeria. The things that interested me were the things that interested a little boy, such as snakes and steam engines, rather than things that have interested me most of the time since.

AM: Well, we'll come back to the snakes and steam engines. That sounds like a title for your autobiography. What about your parentage? Some people go back to the Norman Conquest, and others go back to their parents, but often people go back to their grandparents, and you get a sense of a person from their grandparents, and what they did, and their parents. So, can you tell us something about that?

GA: Looking backwards, my mother was Welsh. She would always describe herself as that, although her father was Irish by descent, though born in Manchester, so, unfortunately, not enabling me to get an Irish passport after Brexit! My grandfather's father had emigrated from County Clare in the mid-19th century. We actually were on holiday in County Clare recently, and it occurs to me I probably really ought to investigate exactly when he did leave. Was it just after the famine, for example? But his son, my grandfather, became a mining engineer. He supported Wales at rugby, which was very important to him. Retired at the age of 80. And he actually married his boss’s daughter. I think his father-in-law was also a mining engineer. But he – my great-grandfather -- was killed in a mining accident in Wales. And his son-in-law, my grandfather, as a young mining engineer, ironically made his professional reputation with an investigation of the causes of the accident, which led to an article in a professional journal. There was a breakthrough about the risks involved. My mother's mother was from a Welsh-speaking part of North Wales, but my mother was of that generation of Welsh people whose parents tended to consider that Welsh was a dying language. So she never learnt it. On my father's side, I think one side of them were actually from London, but the side I know a bit more about were from the south-west of England, I think specifically Devon. A number of them emigrated to Australia, voluntarily or otherwise. By the 1950s or 60s, the family were extremely well-established in Australia, having eventually made their money through sheep farming. They built a number of large properties in different parts of the country, I think particularly Victoria and Tasmania. In the 50s of course it was still not fashionable to have convict descent, whereas the tendency now is it's not quite the Mayflower, but if you're on the First Fleet, you're important in Australian history. So one of my distant relatives wrote a self-published book called 'Convict by Choice', which put forward the thesis that her great --probably great - grandfather, who was convicted for the classic crime of poaching rabbits on a landlord's estate. The magistrate was apparently his own uncle, and the author said nobody could be so cruel as to sentence their nephew to transportation to Australia. So her thesis was that it was a kind of early £10 POM scheme, where the uncle was simply providing assisted passage to start anew. I've always been rather sceptical of that interpretation, but it's an interesting attempt to sort of make the coercion actually consensual. But the connection with Australia has continued in that one of my sisters emigrated there a number of years ago, and my own grandfather on my father's sidetwice emigrated to Australia, but showing a certain lack of decisiveness, came back twice. So we do have quite strong links with Australia. And my parents came from various parts of,, the southern half of Britain and Ireland.

AM: What did your parents do?

GA: My father was a book publisher. He had to leave school at 18 to look after the family after his father left them. And he started in insurance and didn't like it very much, so he wrote to Mr Longman of Longman's Books and said, "I would like to move into publishing". And amazingly enough – I mean, inconceivable now -- Mr Longman gave him an interview and he got the job. So he worked for Longman's for 22 years before moving to another publisher, and that's what took him to Nigeria. He became Longman's representative in Nigeria. That was why he was there. My mother read English at Newnham and joined a graduate scheme for women set up by Unilever. However, when she got to Nigeria, she pretty rapidly concluded that it was simply glorified secretarial work. So she left and she worked in University College, now University of Ibadan, working for the VC as his secretary. And my parents met in her office when he came to the University of Ibadan to try and flog some books.

AM: I see. Right, well, that takes me back. Well, something about their character. I mean, people are strangely reluctant to talk about their parents' character often, but were they encouraging and warm and imaginative or horrid?

GA: They were extremely nice. My mother was, I think, quite a nervous person, but was an enormous emotional support. My father was a slightly more distant... is a slightly more distant person, but enormously enthusiastic about certain things. So I definitely think the reason I became interested in history is that he used to talk about history at the breakfast table or any other table. So when, for the first time, a teacher said ‘we will have a history lesson,’ my ears pricked up. It was the first time anything really exciting had happened at school. So I knew I was going to like history before I had any idea what it was. And he was and is also a great reader. So even today at the age of 100, he is at the moment halfway through a 1,000-page biography of Maria Theresa. So I certainly got the love of history from him. My mother also read a huge amount, of course, as you'd also expect. I had many more political conversations with her growing up than I did with my father. She found it much easier to talk to people she disagreed with, I think, than my father did, at least in those days.

AM: So going back to snakes and steam engines, I didn't think there were a lot of steam engines in West Africa at that time, were there?

GA: Yes, the colonial railways were fairly extensive. And possibly the single most exciting event of my early life, Alan, was when a steam engine called the River Warri crashed through the barriers and blocked a road. And so my unfortunate father was obliged to take me to see it yet again every day until they finally managed to move it. And like lots of little boys are supposed to, I really did actually want to be a steam engine driver. I quite soon grew out of that. Whereas snakes, I was... I mean, there genuinely were quite a few, if you knew where to look. As an adult in Africa, I've hardly ever seen snakes. It's not like Australia. I mean, there are actually not that many and most of them are not poisonous. But when you're very small, the Longmans book of West African snakes had an absolutely compelling, illustration of a spitting cobra. And that really was my idea of a snake.

AM: Did you meet one?

GA: My father used to take me to the zoological gardens in Ibadan, where there was some of the most dangerous snakes in pits. I saw one or two others, but they didn't long survive the experience, because, although my father drove himself most of the time, he did also have a driver from southeast Nigeria, who had a fantastic eye. And I remember us returning with the driver at the wheel, parking in front of our house. And over the entrance, there was an entanglement of green, one might say. And the driver looked up, picked up a stone, threw it, and then there was the sound of a snake falling down, dead, hit just behind the neck. And he did the same to other snakes. In i a different era, he could have been a professional sports person, I feel, instead of which my father lost contact with him after a letter saying he was going home to join the Biafran army.

AM: Right, well, moving on, your first school was in..?

GA: My first school was actually the senior staff infant school of University College of Ibadan, where I was for two years.

AM: Was it mixed colour-wise?

GA: Yes, it was, yes. And it was also...there were boys and girls and Nigerians; mostly Yoruba and expats. I enjoyed being there. I don't remember very much except for a fire in the grounds that was particularly exciting, because a whole lot of snakes were escaping from it. But it gave me, I suppose, a slightly positive view of school. I think that's the main thing I can say about it.

AM: And then, moving on, at what age did you leave ?

GA: We left when I was six and I went to a convent school in the Sussex village of Storrington, because of my parents. They did live in London briefly, though I don't remember that at all. They then moved to Sussex.

AM: So you came back to England when you were six?

GA: Yes. I had been there on leave before, but I don’t have any memories of England until the age of six. We arrived .just in time for a famously cold winter. .. I think it was, it must have been about 62,-63.

AM: That's right, it was 62-63. I was in Oxford and it was very cold.

GA: It started snowing, as far as we were concerned, on Boxing Day and it just was white for months and months after that. So I got a quite misleading idea of how cold this country is most of the time. Yes, I went to the local convent for a couple of years, as did the elder of my sisters with whom I used to walk to school.

AM: Did this instil a deep love of religion?

GA: Not really. I don't think I really enjoyed that school, though I didn't dislike it either. But, I mean, for one thing, it was Catholic and my parents were both Protestants. I remember my mother being outraged to discover that the nuns were teaching us about purgatory, which of course is not a Protestant belief. Although generally they had separate sessions, I don't think they were services, but there was a separate session for the Protestant children while the Catholics were having their service. Everybody was either Protestant or Catholic, there was nobody else. But I guess it was a reasonable school. I then went to prep school in Worthing for five years, which I didn't enjoy, though I don't think that's the fault of the school. I was just at an age when having teachers telling you what to do all the time was quite galling.

AM: You were a boarder?

GA: No, it was a day school and I came on the bus.

AM: No cruelty? No bullying?

GA: No, I do seem to remember I was involved in a lot of fights, but I don't actually think there was much damage done. And I had a very strong sense that it's very important to stand up to bullies, whether on your own account or on somebody else's account. That was a big part of how I saw the world when I was that sort of age. But I actually don't think it was a particularly violent school and there was no corporal punishment in any of the schools that I attended. I went on to secondary school: Sevenoaks School in Kent. There I was a boarder and actually it really wasn't at all like the stereotypes. I think one theory might be that it was partly because. there was quite a lot of supervision of prefects. So one scenario in which I think bullying happens is when older children have got free reign, perhaps as in the 'Lord of the Flies', which is too much of a generalisation, but in any case on the whole there was a very, we would now say supportive culture. So it was actually a place I found hugely more interesting than my previous educational experience. And I was pretty happy to be there. It was full of interest.

AM: We'll come back to it because I omitted to ask you a question. I came back when I was five from India and I often sort of date my anthropological interests from the culture shock coming from the remote part of the Raj and the Empire back to an equally cold winter in 1947. But it was the learning the customs and culture and then at boarding schools, which I think gave me a sense of relativity that this wasn't in the blood. I had to learn it and perform in the Western ways. When you came back at age six did you get any culture shock that you can think of?

GA: I think I must have done, but I must say if there was it wasn't all that severe Much later I had a girlfriend who had spent time when she was very little in I think what is now Zambia and therefore she had at that time quite a strong Southern African accent. And so she was picked on at school for that reason. Whereas I didn't have that experience. I mean partly that there was no such thing as a distinct colonial accent in West Africa. There weren't enough, which reflects the nature of the colonialism there. There weren't enough Europeans for that to be a linguistic possibility probably.

AM: Okay, well coming back to Sevenoaks, presumably you streamed towards the end. What subjects did you gravitate towards? I assume history, but I don't know.

GA: Yeah, I did think, but not for very long, about doing sciences. But in the end, for A level under the traditional English system of choosing three A level subjects, mine were definitely History, definitely English and I would have loved to do economics, but because of a timetable clash I did Business Studies instead. Which actually was quite interesting in that it did provide introductions to little bits of social psychology for example and organisation theory that I wouldn't have done in economics, and the economics I learnt later anyway. So that although I was slightly resentful at the time at having to settle for what I considered a poor fourth choice, actually it was quite empowering as we would later say.

AM: Were there any teachers who you found particularly inspiring or helpful?

GA: Absolutely, yes, I was incredibly well taught. There were English teachers who were wonderful at making one realise how exciting what one was reading was.

AM: Do you remember any of their names?

GA: One of them was Mr. Hennessey, he was one of a number of teachers who were extremely inspiring about English literature. But he actually supervised my first dissertation which arose because the English language O level syllabus had an option where you could write an extended essay and he suggested I might write a fiction. I was flattered to be asked but I thought I'll stick with what I had first thought of. So it was actually an argument for why there was the case for a united Europe. And that was one of the earliest things that interested me politically. I don't know what he personally thought, but he was an extremely good supervisor on that and sort of asking me questions to think through what I thought. The business studies and economics teacher, Casey McCann, was a very charismatic Irishman who made lots of funny jokes, but also he advised me to do politics. He was very keen that I should go to the LSE to study politics. But I learnt a huge amount from him. He was also an inspiring individual I would say. He eventually became a head teacher in Brazil. And I saw him not too many years before he died. I think he died out there. And then for History, there were a whole bunch of teachers all of whom differed from each other greatly in their style of teaching but in their different ways were all extremely good. So they were very encouraging and I really was incredibly fortunate in my secondary and particularly A-level tuition.

AM: One of the things that happens to some people anyway, to me, at about the age of 15 or 16 is that you are confirmed into the Church of England if you are C of E. Or even if you are not, quite a lot of people go through a kind of religious phase in their middle or later teenage years. Did that happen to you?

GA: Yes, I was indeed confirmed in the C of E. I was keen but without, in those days, enjoying services. I was always looking at my watch and counting how many pages of the service sheet were past. But I did regard it very much as a matter of a personal relationship with God. And there came a point in my 20s when I felt I didn't really have one. So that was a point when I didn't become an atheist but I genuinely wasn't sure what I believed. Which has pretty much continued though partly because of marrying a very committed Anglican I have continued to go to church from time to time. And I like the Church of England., I think there is a lot of intellectualism at the higher levels of it. There are lots of very thoughtful priests. So I am perfectly happy to call myself an Anglican these days, I must say. There was a phase when I would have said I was agnostic. On the whole now I would describe myself as an Anglican. But in a way the things that I most appreciate about the Church these days are not what attracted me to it as a teenager, which was very much the personal relationship which of course as we know is doctrinally central both to Christianity in general and to Protestantism in particular. But these days I love the ritual. Yes, there has actually been a kind of inversion in what I think about it.

AM: Interesting. The other two things that... Well, two of the things that are important in boarding schools. One is sport - games. Did you play and were you good at any sports?

GA: I was very enthusiastic. I was reasonably good at rugby and soccer and hockey. But while I was recovering from a broken collarbone, sustained while playing rugby, I discovered I was best at long-distance running, which the school actually regarded as one of its three major sports. So after that I switched my focus to cross-country running. I suppose I was at one time the second best runner in the school. I was never the best. But it was a team event and I much enjoyed the team aspect. But I must say for me the biggest, the most emotional sporting thing was house competitions against other houses where you played every sport. I am sure it wouldn't surprise you. There is a strong sense of solidarity with members of your house, particularly in the boarding houses, who tended to do disproportionately well in relation to their numbers because of their extra commitment.

AM: Another thing that also occurs at that time is either an interest or non-interest in music. Has music been important in your life?

GA: It's always been part of my life. Not as important as for some people. But I suppose in my teens, 20s and 30s, I did spend an awful lot of time listening to a rather small number of singers, above all Bob Dylan, who I used to listen to in Ghana, for example. I'd have a particular LP at the time, a particular album which would obsess me for a few months and then I'd move on to a different one. And I always enjoyed some elements of classical music, but my parents were huge opera fans, which actually I think did slightly deter me. That was one area in which I slightly rebelled. I wasn't as enthusiastic, though nowadays, I think opera's fantastic, but in my teens I was more interested in particular kinds of pop music. [At Cambridge] I remember Christopher Ricks, of course, giving his, I think, possibly annual lecture on Bob Dylan, which was very interesting.

AM: And the last thing, did you have any particular hobbies or passions that you really loved doing around that age?

GA: I had an unhealthy interest in war games. I spent quite a lot of time playing, not so much Risk, which I regarded as a slightly inferior game because of the strong element of chance, but more Diplomacy, which has no dice, and also Avalon Hill war games. And I only gave those up really when life became too busy, but for a long time...

AM: At what age was that? When did life become too busy?

GA: I think possibly when going to the LSE to teach.

AM: So, you were 14 to your mid-20s?

GA: Yes, although by then, instead of playing regularly and with a lot of people, it was down to just occasional weekends with a particular friend. But in fact, my first publication was in a Swiss magazine, and it was a defence, it was a Russian defence for a game called Stalingrad, which would have been better called Barbarossa because it was the German invasion. And I was supposed to be playing by post with this Swiss guy, and I think he couldn't perhaps work out how to get through the defence, so he decided to publish it instead. So he never actually played the game, but that was my first publication, I'm slightly embarrassed to say.

AM: So, moving on, you came to Clare College, Cambridge, to read history?

GA: Yes.

AM: And were there any teachers here, or lecturers, who particularly influenced you or inspired you?

GA: Charles Parkin was our Director of Studies, and he was, as he would quite often comment, a Northern Grammar School product. I think he did go to Manchester Grammar School. He was an incredibly dedicated Director of Studies who was extremely close to his students and who I respected enormously. In contrast, the best-known historian in Clare was Geoffrey Elton, who would affect not to remember who the Director of Studies was on the grounds that he hadn't published very much.

AM: Did you know Geoffrey?

GA: Not very well. I attended a few of his lectures, but I didn't go regularly to them because I felt they were... they were too much a kind of party line. Where I thought he was really good, Geoffrey Elton, was when challenged. When, for example, one of his well-known books, of course, was 'The Practice of History', and I remember him being challenged on some of the more extravagantly positivist things that he said in that book, and he absolutely seamlessly switched to a much more nuanced position. And there was a certain theatre when he was arguing with people, and he was well, well worth hearing in those contexts, but I couldn't say I was a fan of his, partly because of his attitude to Charles Parkin, who I very much liked. But I think in the university, I had the good fortune to hear the young Simon Schama. There were about 20 of us who would regularly go to his lectures in those days. Of course, lectures, as today, were optional, but in those days you'd also have, unlike today, several lecture courses that you could take on, for example, modern European history. So the result of that was that most lecturers had the experience that they might start with 50 people in the room, second week it would be down to 20, and the third it might be four. Simon Schama always held about 20, 25, and I was one of those 20 to 25. And the most striking thing was, in terms of exam fodder, they were literally useless. I didn't take any notes at all. And he did, I think, come with notes. I know that because he would start by looking at the lectern, and there was a piece of paper on the lectern, and he would look at it again, a couple of times in the first five minutes. And there was obviously a plan there, and then he would just forget that and ad lib for the rest. And it was just fantastic. It made you feel, or not feel as if you were walking along the banks of the Seine in 1793, but as close as you can do to having that experience. Now, if I hadn't already wanted to be a historian, that would have convinced me. And it also underlines the value of a kind of teaching which isn't oriented at very specific goals, but which unfortunately the system doesn't have room for these days. I mean, that was a Schama that was, in a sense, quite different from the TV Schama that we know today, where he's obviously very disciplined and focused on the script and so on. The young Schama was far more spontaneous, but very exciting. And then Jonathan Steinberg was certainly a favourite. ... He was at Trinity Hall..... He only supervised me once for revision supervision, but he was,...again, there was a certain group of about probably 15, 20 of us who would sit, would attend every Steinberg lecture. They were always at 9am, which for undergraduates in that era, as today I think, was quite a challenge. But we were always there, and in each set of lectures he would make the same jokes. He'd never repeat them within a series of lectures, but all of us, because we all went to them all, we would sort of look at each other when they came out. You know, his one to illustrate ‘historical accident’: a boxer said, when knocked out by Joe Louis, ‘I zigged when I should have zagged.’ That was a regular. But he was far more intelligible and had far more coherent arguments than Schama. But again, I would say he too was somebody who was inspiring beyond his particular subject matter. But I had many, I really had many good teachers. Actually, Geoff Eley I would particularly mention. Geoff Eley was a research fellow, was he in King's? ... I associate him with King's because he was a regular at the, what became known as the Social History Seminar that Gareth Stedman Jones hosted here in King's. But Geoff Eley, I well remember my first supervision with him, which would have been my fifth supervision in Cambridge. And the question unbeknown to me was one on which he would make his name, which was really, why did Germany manage to both industrialise and at the same time fail as a liberal democracy? It was put more eloquently than that. But this was a question of which I thought I had a good answer from A level, albeit for a slightly different question. So I wrote my essay, handed it over, sat down and waited for the applause, and he absolutely shredded it, totally took it apart. And the next week I wrote a far better essay this time on the 1917 revolution, no it was on Stalin. But he really forced me to raise my game. So I told him this when I met him years later, but he'd completely forgotten. But he did actually make a real difference to me, he did improve me as a historian.

AM: What years were you at Clare?

GA: ’75 to ’78.

AM: Why did you then decide to immediately go on to do African history at Birmingham?

GA: Well actually before going to Clare I took a year off, or rather I did the Cambridge exams in the seventh term of sixth form, which you could if you were lucky enough to go to the kind of school that could afford that. And the subsequent two terms I taught in Kenya at what in those days was called a Harambee school. I say in those days, they don't exist anymore. But they were community funded, locally community funded schools. Whereas the top 7% of primary school leavers went to government schools, the second 7% went to Harambee schools and the rest didn't go anywhere in those days. And so it was a very under-resourced school. I was actually the most qualified member of staff, if you judge it by formal qualifications. Though the deputy head had actually done a bit of teacher training, I think I'd had 48 hours or something. So I think it was one of these cases where I don't know whether the students learnt much. I was teaching maths by the way, but I learnt a huge amount. I mean it was just a fantastic experience. I travelled all over Kenya and to Tanzania. So it was in my second year here where an old friend, I mean by then not that old, I met him in Kenya, he was teaching at a different school, Paul Coby said to me, ‘We've seen rural East Africa, let's try rural West Africa.’ And we persuaded our respective colleges to give us some money and raised a bit of money from other sources. And our respective final year dissertations were both on Ghana. And the reason they were on Ghana was because both our directors of studies, in my case Charles Parkin, couldn't think of anybody in the history faculty who could supervise, although there were two excellent historians of Africa, but neither of them worked on West Africa. So we were directed to John Dunn. And John Dunn supervised my undergraduate dissertation.

AM: He'd already worked with Jack Goody, had he, on Ghana?

GA: He had.

AM: And Sandy Robertson.

GA: Exactly. He and Sandy Robertson wrote their joint book. That was in the recent past. And that meant John also, John was able to give us a very useful contact, who was a King's alumnus in Ghana, and who was managing director of the Volta Region Development Corporation, which proved a very useful contact. But if it wasn't for John, I'd probably have, I might have ended up working on somewhere else. The experience of doing research in Ghana for eight weeks during our second long vacations, was enormously influential. So after that I was definitely planning that, if I did a PhD, would be on African history, and specifically economic history.

AM: And then did you immediately go into the PhD at Birmingham?

GA: Yes, yes, immediately.

AM: And Hopkins is a famous name. What was he like, as a supervisor?

GA: Yeah, I went to Birmingham purely to work with him, because I read his first book, and I thought I want to be supervised by the author of this. I was offered a place at SOAS, but Roland Oliver, one of the founding founders of African history as a specialism, said to me, ‘you know that the only pukka economic historian of Africa in this country is Tony Hopkins’, which indeed I'd already worked out He was a wonderful supervisor, I must say. Really extraordinarily good and exciting and critical, just the right amount. He was really everything you could hope for and more as a supervisor. So there's no doubt I have modelled my own supervising to a great extent on Tony's, although there are certain differences. We're both pedants, but he is better than me at knowing how to calibrate criticism or comments on a piece of student work. I tend to give the student more than perhaps they need at that point in their career, which I think is one of the skills of teaching that I've never quite mastered. I give more than is probably really necessary, whereas I admire Tony's sort of calculated restraint.

AM: I have an oversimplified idea that basically until a certain point in the last century, people thought Africa didn't have a history, that there were no sources really and you had these tribal peoples and then the West came, so the history of Africa was the history of Western colonisation and so on. Then at a certain point it changed and people began to feel that there was much more history to be discovered in Africa. Was that a true guess and if it was, at what point did that occur?

GA: Yes, I think the idea of Africa as not having a history, I think somebody ought to research how far that view was held in 18th and early 19th century Europe. I say that because some of the early European accounts show an interest in the history of the Ashanti Kingdom or wherever it is that they're visiting. But yes, I think broadly there was a major change roughly associated with the colonisation. The first, not the first economic history, not the first book of economic history written about Africa or even about West Africa, but the first book in the continuous professional study of West African economic history and one could actually say history as a whole, was Trade and Politics in the Niger Delta by K.O. Dike, a Nigerian historian who did a PhD in London. His book was published by Oxford University Press in 1956, as it happens, the year I was born. So I think of myself as more or less coterminous so far with the study of African economic history, though of course I didn't know anything about it until I was an undergraduate at Cambridge. And the real take-off was late 50s, 60s, and that included the study of Africa's economic past, which then went into a kind of recession in the late 80s, 90s, for a couple of reasons including, I think, a general atmosphere of pessimism about the future of Africa. Because of course what you think of, what people think of contemporary history has a great influence on the questions that are asked and fewer people I think were interested in studying Africa's past, including its economic past, when its future seemed so grim. And that's one of the things that changed in the beginning of the present century, changed for the better. Also I think the cultural turn undoubtedly meant that we had more people writing on, for example, no longer on the history of African labourers, but on what European colonial officials thought about African labour, a kind of introspection in European terms.

AM: The name that keeps recurring in my mind, so I'd better get rid of it, is John Iliffe. Because he was at St John's and I dimly remember he was an African historian. He wasn't someone you thought about studying with or was it a different...?

GA: I think it was because I had not met him. I never saw him as an undergraduate. Partly because Cambridge had and still has the -- to me -- eccentric rule, which at most universities would be considered completely daft, that you if you're doing a dissertation on a subject, say, within African history, you could not take the Part II, the final-year course that corresponded to it. So I didn’t take the African history paper while I was here, though I went to one lecture by John Lonsdale, which was an extraordinarily good lecture, and that was it. That was all I saw at the time of those two illustrious pioneers of African history in Cambridge. Of course, later on I got to know both of them, particularly John Lonsdale. I don't think I even thought about the possibility of studying East Africa because of having done some research in West Africa. That really led me to think that it's West Africa I want to study.

AM: Okay, so after the PhD, you went and taught in Africa, or what was the next stage?

GA: The immediate next stage was... I had a one-year temporary lectureship at Birmingham when Tony Hopkins was on leave. The interview was a few days after I had failed in an interview at SOAS for a lectureship in African history. The successful candidate was my girlfriend at the time, who was a year behind me, but I must say I think she thoroughly deserved the appointment. And I also share with my students and mentees the thought that to describe the head of the institution at which you're being interviewed as ‘arrogant’ is not good interview tactics, but the then director of SOAS said something extraordinarily arrogant about the teaching of Ghanaian history!

AM: Who was it?

GA: I forget his first name, Cowan, Southeast Asia. I think he was the historian of Southeast Asia. We didn't have the opportunity to meet after that disastrous encounter. This also... this may not be worth including, but there's also another aspect to that story that was funny.I In those days it was commonly advised that if you're going for interview, wear what you feel comfortable in. What I felt comfortable in did not include a tie. Too many years of public school, I think, had affected that. So I went along open-necked, with jacket, but open-necked. And when I didn't get the job, I had actually a very nice letter from Roland Oliver saying I hope you don't feel insulted, but Susan Martin showed , among other things, a great sense of occasion. I wrote back saying, she's excellent, you don't need to explain or justify your decision. And that was all I said, I didn't think anything about the ‘sense of occasion’. I assumed that the reference to the sense of occasion was my unfortunate remark to the director of SOAS. But in fact, many years later, I learnt something else about that occasion:decades later, or to be precise, early 2000s. Roland Oliver, I should have said, was one of the senior historians of Africa, the founder of African history at SOAS. He and John Fage, director of the Centre for West African Studies at Birmingham, were the two founders of African history in Britain. And they were also the two founders of the Journal of African History in 1960. When I became an editor of the Journal of African History, John Fage had died by then, but Roland remained on the board, and he would always come to the annual meeting. And we, the then editors, took Roland for dinner. This was in Seattle. After dinner, we all returned to our conference hotel. And myself and one of the other editors were sharing a room, so I have a witness for this story. We emerged from the elevator on the same floor as Roland and his second wife, Susan Miers. And because Roland was of an age where he was hard of hearing, he was speaking very loudly. And as my editorial colleague and I were walking the opposite direction, we heard Roland say, ‘Such a nice fellow, Gareth, it's such a pity we couldn't hire him at SOAS, but he didn't even wear a tie!’ I don't think that was actually a reason why I didn't get the job, but I thought it was hilarious that he remembered it years later.

AM: Well, I don't usually intervene, but I have a tie-wearing story of SOAS as well. A friend of mine, Stephan Feuchtwang, who's an expert on Chinese anthropology, left SOAS because he used to go to the cafeteria without a tie on. And he was summoned by the head of department, who was my PhD supervisor, I think Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf, if I've got the story right, and he said, Stephan, would you mind? It's customary to wear a tie. And Stephan was so furious that he left and went to some other university. That was a bit earlier. We're just coming to the end of this tape, so would you mind if we did a few more minutes? GA: Yes, sure.

AM: So, your main work obviously is on African economic history. Tell me something about that and about working in Africa.

GA: After a one-year temporary lectureship at Birmingham, I went to teach at the University of Ghana for three years. We had a nearly one-year unofficial sabbatical when the campus was officially under workers' occupation, following the major conflicts in 1983, which was a pivotal year in Ghanaian history. That was an extremely valuable experience for me, teaching at the University of Ghana. It was also seeing political conflict quite close up for the first time, for the only time in my life. I learnt a lot about how things can happen from a very short period. I also took the opportunity to travel. So, rather than using the breaks from teaching to write papers, as I perhaps should have done, I took the risk and I've been lucky enough to get away with it. It's not one I'd really advise younger people to emulate in the present professional context. I did an awful lot of travelling, mainly by public transport, in other parts of West Africa and indeed in other parts of Africa. History is obviously not anthropology, but I do think that it helps to have been to the places that you write about. I've got a perhaps unjustified bit of self-confidence from the feeling that, if I am talking about Mali for example, at least I remember Mali in such and such a specific moment. Of course, it's changed. So, for me, that travelling was very important, I think not only psychologically, but also intellectually in various ways. After the University of Ghana I had a three-year ESRC postdoc at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies. I left that fellowship early in order to take a teaching job at the LSE. And yes, the majority of what I did was African economic history.

AM: I often ask this at the end, but it's perhaps good to ask you now. You're on your desert island and you're allowed one of your books or articles to read again and again for the rest of your time on the desert island. In other words, which do you think is your most important contribution?

GA: That is a very hard question.

AM: You're allowed two if you like.

GA: It probably would have to be my book, 'Labour, Land and Capital in Ghana', partly because it took so long. And it does very well reflect what I thought on many subjects up to 2004 when I finished it. But it's not the... undoubtedly, it's articles that I've written that have been much more read. Like yourself, I've reached this stage, and you've reached this I'm sure long ago, where you find yourself cited more often than you think you're actually read. And that's certainly true with the book, partly because it's too long. But I think probably I'd take that.

AM: The title suggests Karl Marx, obviously, 'Labour, Land and Capital', which prompts the subsequent question of if you had to choose one dead great theorist who has influenced your work most, who would you choose?

GA: It would have been Marx for a long time. Though. 'Labour, Land and Capital' also referred to l the classical economics idea of the factors of production as well. And I've always taken very seriously both, shall we say, the rational choice tradition and its critics of varying kinds. But it's very hard to think of anybody who would be more interesting to talk to over a long period than Karl Marx. I think that's true even though there are a lot of areas on which other people have said equally or more interesting things. But if it was Weber or Marx, I would possibly slightly choose Uncle Karl.

AM: Moving to the LSE, I was at the LSE much earlier before you and I have many friends there. This is when we met in the 90s at an Institute of Historical Research seminar on global history. Those people presented talks on Braudel and so on. I did Braudel, so I remember that. And the person who was the force behind it to a large extent was Patrick O'Brien, who I think has influenced you. Can you say something about Patrick?

GA: Patrick has greatly influenced me. I think that seminar was the beginning of what he would call the renaissance of global history in Britain, maybe even in Western Europe. That's more complicated. One of the reasons I thought that seminar was so good was the way he would begin with two things. One was a manifesto. I mean, when I organize seminars, I just announce a list, a title of the series and a series of names and titles. Patrick, as we know, believes you need to have a manifesto, a proper page or two, setting out why it's interesting and important. But even more important was the fact that, as you remember, he would always say, this is not a research seminar. It was a conversation among specialists. That was the point, among specialists on different areas. And I thought that was exactly the most creative way to approach the subject of global history. Perhaps there was no other good way of doing it, but the key thing is he did it and it led to extraordinarily interesting discussions. Another very good thing about Patrick was he also knew when to move on to something else. He did notice when the wheels perhaps started to spin a bit. After a few years, though the seminar was very popular, it had never been more popular, the papers were good, the discussion was good. But I think he, I'm guessing, but I think he thought that intellectually it was not actually as innovative as it had been in the first few years. In a way we'd done the easy stuff and instead, of course, we had his project funded by Leverhulme for bringing together four institutions in different parts of the world to study global history. And that was another, I think, very successful intellectual adventure that brought together people who in many cases wouldn't otherwise have met, let alone talked with each other. And the whole was greater than the sum of the parts. So that was tremendous and it was very fortunate that he was willing to come to the LSE on his retirement from the Institute of Historical Research to be the first Centennial Professor in economic history. So I had the pleasure of teaching with him as well at Master's level. He was an inspiration to the students and he's always been, ever since I first met him, an inspiration to me. And I also think that like Tony Hopkins, Patrick is, of course, admirable, as you are, Alan, for productivity after retirement. So I'll do my humble best to do the same.

AM: We're talking on the edge of retirement. Two of the people who were involved, I imagine, then, and who I know, one was a Japanologist, Kaoru Sugihara, and the other was a sinologist, Kent Deng, both economic historians. So they're both my friends and I respect. That takes me to, that was another feature of it, that he brought in people from entirely different parts of the world, not just the West and Africa. And I noticed in your CV you teach global history, including Asia, South America and so on, and I'm particularly interested in Asia. So I was wondering how do you manage to absorb such wide and different civilisations together for undergraduates and others to be able to comprehend them?

GA: I certainly wouldn't claim to have the same degree of knowledge of the other continents that I teach, but this actually goes back to when I first arrived at LSE. There was a master's course, the core course for the master's in economic history, option B, Economic Development of Africa, Asia and Latin America. The course itself was called Growth, Poverty and Policy in the Third World, remember that phrase? Since 1850.

AM: You know who invented it? Sorry? You know who invented the phrase? Peter Worsley. GA: Oh, that's right, Peter Worsley, yes. And so I'd had to teach Latin American, South Asian, and and also a bit of East Asian economic history then, but because of the way master's teaching goes, I didn't have to give full lectures. On the other hand, again from the day I arrived at LSE, I actually had to teach Indian. I had to give seven lectures on Indian economic history from the Mughals to the 1980s, which was a great deal of work. I mean, the answer to your question is by a great deal of reading and also learning a lot from colleagues who were genuinely expert in these fields. My approach to PhD supervision has been that I have occasionally supervised people on regions other than Africa, but I've always felt that it really needs, in that case, to be a co-supervision if at all possible. In one case, sadly, it wasn't possible, but usually there's somebody else who reads the language, certainly the language of the primary sources, and is at least a regional expert on something, even if I know more about the specific economic history issues.

AM: When you said that you did it by reading a lot of books and talking to your colleagues and so on, I noticed I think you're starting a teaching course on methods of history or methodology of history. I've always thought that the great world historians, Bill McNeill and Braudel and so on, and the great older ones, back to Montesquieu, achieved a sort of global view by having certain techniques of comparison. Weber's another example, like ideal types and so on. Do you teach that or are you interested in how a historian can approach such diverse civilizations and bring them into comparison?

GA: I think that it is interesting that by the 2000s, you were beginning to see the emergence of young scholars starting PhDs or even finishing them who defined themselves as global or world historians. That marked a change from my generation, I would even include Patrick in this, in that we thought, and I still think, that actually it's a great help to know a lot about somewhere before you try and at least write about other areas. So, I regard Ghana as my observatory on Africa and beyond, not because I can comprehend all perspectives you could have from that particular point, but you have to start somewhere. But beyond that, I think the idea of focusing on particular areas is essential. That's actually what we did in teaching at the LSE. So, for Asia, Africa and Latin America, we picked certain countries to compare, and the exam questions would never ask about the whole of Asia, the whole of Africa or whatever. It would always compare something in relation to Brazil and Nigeria or India or wherever. And I think Ken Pomerantz is right that the idea of a ‘core’ is a good idea, that it doesn't always make sense to compare England and China, as you know very well, because you are comparing across two very different scales. From some perspectives...but again it does also depend on what the question is. From some perspectives, it is legitimate and not only legitimate, but a good idea to perhaps to try and think at a continental level. And I think in the case of Africa, I don't think it makes much sense to write about the economic history of the physical continent as a whole, because much of North Africa -- above all Egypt -- is just so different in so many ways from most of sub-Sahara Africa. But if you are talking about the history of religion, both Christianity and Islam crossed the Sahara ages ago and Muslims in Africa had the same focus as Muslims everywhere else in the world. So I think it does depend on what you are looking at, but basically I think you to make this comprehensible or make it possible to talk about it seriously, you have to have some principles of selection.

AM: The other difficulty, you basically label yourself as an economic historian, but if you are doing world history, in most of the world economics is heavily embedded in politics, religion and society. How do you deal with the fact that you at the same time have to move out of economic history into all those other fields?

GA: I take it that in all countries, everywhere economic activity is embedded in culture and politics: even in a market economy, actually what is in our heads and the political decisions that shape economic activity are also very important. So I have always seen myself both as an economic historian certainly, but as an economic historian in the broadest sense. I am interested in every aspect of economic history and I find it very congenial to exchange with colleagues whose specialism is outside economic history or of course outside history. I did read quite a lot of anthropology in my youth, at the ages of 18, 19, 20, 21. I particularly read quite a lot in several disciplines at an age when it was still not part of a particular project. It is one thing later on to think I need to read this article from anthropology because it would be helpful for this particular paper I am writing, but when I was to some extent trying to educate myself, I just read more broadly to find out who this guy Claude Lévi Strauss was and that sort of stuff, not because I ever expected to apply it.

AM: Were there any questions that really, I mean you didn't anticipate it, but that you would have really liked me to have asked you? I haven't asked you about your family, which is..., you have referred to them, but your parentage and so on, but sometimes people say that, oh my daughter would kill me if she ever met you. But is there anything else you would have liked me to ask you?

GA: It is true, as with everybody, family shape what you can do, motivation, support and so on. Actually my published output went down during the years when we had young children for extremely good reasons, though I would actually say that was because in those days the LSE was not very good at managing the workload of junior colleagues, which it has become very much better at more recently. But I think, I mean I have actually learnt a lot from Pip, who herself was trained in anthropology and we met when she was at SOAS. I was not at SOAS of course, having not got the job, which was probably just as well because actually we met when she was writing a paper on cocoa farming in West Africa and wanted to consult me about it when I was at the Institute for Commonwealth Studies. But they have been enormously supportive as have all my three children, the youngest of whom did actually do history at Cambridge, finishing in 2016: her last two terms were my first term.

AM: That's nice. Well we'll end there but mentioning cocoa farming in West Africa can hardly be uttered in my presence without mentioning my dear friend Polly Hill. Did you know Polly?

GA: I did know Polly. Not all that well but when I did my undergraduate dissertation on Ghana it was to a great extent about cocoa and John Dunn could have sent it to her as the great expert to ask for comments. Because John knew Polly well, he wisely did not, whereas a future friend then at the University of Cape Town, Paul Nugent, his undergraduate dissertation was also on cocoa in Ghana and his supervisor did not know Polly personally and sent the essay to her and she responded beginning with the sentence, ‘The one thing I cannot stand is intellectual dishonesty.’ I mean (in square brackets), there are plenty of things she couldn't stand but that was no way to respond to an undergraduate. So I didn't meet her then. Then there was the problem that when I arrived at Birmingham she and Tony Hopkins were having a bit of a spat so I wrote to her first when I was in Ghana so I could put it that way/ She very kindly invited me to lunch at Clare Hall. So I had a very interesting lunch/ I thought she was slightly spiky but it was a very interesting lunch. Even then when I was just a PhD student I was struck by how insecure she felt. At that time John Eatwell had edited the New Palgrave Directory of Economics' which contained only two entries on economic historians and she was one of them. That's if you count her as an economic historian, which I would but of course she was also an economic anthropologist and so on. She was saying, nobody appreciates my work and I said look you are up there in this book, only the great Alexander Gerschenkron is there alongside you to represent economic history/She said yes but that's because John Eatwell likes me. And I thought well, I'm sure he does but that's not why he put you in the book. I don't know whether you felt this but I think she found it very hard to accept a perfectly sincerely meant compliment. The later stage was when Gervase Clarence-Smith from SOAS and I invited her to a conference we were organising on the history of cocoa farming in three continents. We had this problem. you can't have a conference on that theme without inviting the author of the most famous work in this field. But, on the other hand, if Polly comes she is likely to catch fire. So I wrote to her and she replied saying (this is from memory) ‘Seeing as, if I do not, the historic achievement of the migrant cocoa farmers of southern Ghana will go unremarked at your conference, I accept your invitation.’ I wrote back that everyone coming to the conference will be very aware of the historic achievement of the migrant cocoa farmers of southern Ghana because they will have read your book, whether their own research is on Brazil or anywhere else. I added that I was aware that it was now a long time since she herself worked on Ghanaian cocoa farming but would you consider commenting on the later work in your field, for example Sara Berry on south-west Nigeria. Sara Berry wrote this very good book on cocoa farming in south-west Nigeria which isn't actually dedicated to Polly Hill but it's as good as. It is really a tribute to her though its chapter organisation is much more logical!. And she replied ‘;I cannot abide the work of Sara Berry’ But in the end the correspondence concluded when she said, I think in a moment of definite insight. ‘I'm not very good at commenting on other people's work.’ And after that I did have one further contact with her which was when 'Migrant Cocoa Farmers of Southern Ghana', her first and best book was selected to be included in the Classics of African Anthropology series published by the International African Institute. The Institute asked me to write a new introduction and luckily I knew the secretary of the Institute who was a good friend and she would (very naughtily) send me copies of her correspondence with Polly. And so there's one saying I don't want to have anybody writing anything, Meyer Fortes already wrote a preface to the original. And so Elizabeth Dunstan wrote back and explained unfortunately the price of being included in a ‘classics’ series is to have some younger person writing an introduction. She then said ‘well I suppose Austin is as good as I'm going to get’. We then made the mistake of sending her my draft introduction which she absolutely hated because I had tried to put her work in the context of earlier work by other people such as Margaret Fields, another very interesting and slightly unusual scholar. And also later contributions including Sara Berry! She was absolutely furious and particularly because I also mentioned various econometric contributions. Of course by that stage she'd long forsaken her early interest in quantification. But I did actually hold my ground. I declined to change anything except I added one extra mention of Sara Berry which I thought was deserved. But Polly was absolutely brilliant, a fantastic scholar who I think is not read nearly enough these days. So I do actually try and mention her in many contexts and I'm very glad you mentioned her to me today.

AM: Well, I did an interview with Polly which I was not enormously looking forward to but she was actually very sweet.

[AM – Alan Macfarlane; GA – Gareth Austin]

AM: It's a very great pleasure, after many years of knowing you, Gareth, to have a chance to talk about your life and work. I'm going to start by asking when and where a person is born. GA: Thank you very much for asking me, Alan. I was born in Ibadan, Nigeria, while it was still a colony. So, in 1956, four years before Nigerian independence, and six years before my parents returned to Britain, bringing me and my sisters with them. So, my first memories are obviously of Nigeria. The things that interested me were the things that interested a little boy, such as snakes and steam engines, rather than things that have interested me most of the time since.

AM: Well, we'll come back to the snakes and steam engines. That sounds like a title for your autobiography. What about your parentage? Some people go back to the Norman Conquest, and others go back to their parents, but often people go back to their grandparents, and you get a sense of a person from their grandparents, and what they did, and their parents. So, can you tell us something about that?

GA: Looking backwards, my mother was Welsh. She would always describe herself as that, although her father was Irish by descent, though born in Manchester, so, unfortunately, not enabling me to get an Irish passport after Brexit! My grandfather's father had emigrated from County Clare in the mid-19th century. We actually were on holiday in County Clare recently, and it occurs to me I probably really ought to investigate exactly when he did leave. Was it just after the famine, for example? But his son, my grandfather, became a mining engineer. He supported Wales at rugby, which was very important to him. Retired at the age of 80. And he actually married his boss’s daughter. I think his father-in-law was also a mining engineer. But he – my great-grandfather -- was killed in a mining accident in Wales. And his son-in-law, my grandfather, as a young mining engineer, ironically made his professional reputation with an investigation of the causes of the accident, which led to an article in a professional journal. There was a breakthrough about the risks involved. My mother's mother was from a Welsh-speaking part of North Wales, but my mother was of that generation of Welsh people whose parents tended to consider that Welsh was a dying language. So she never learnt it. On my father's side, I think one side of them were actually from London, but the side I know a bit more about were from the south-west of England, I think specifically Devon. A number of them emigrated to Australia, voluntarily or otherwise. By the 1950s or 60s, the family were extremely well-established in Australia, having eventually made their money through sheep farming. They built a number of large properties in different parts of the country, I think particularly Victoria and Tasmania. In the 50s of course it was still not fashionable to have convict descent, whereas the tendency now is it's not quite the Mayflower, but if you're on the First Fleet, you're important in Australian history. So one of my distant relatives wrote a self-published book called 'Convict by Choice', which put forward the thesis that her great --probably great - grandfather, who was convicted for the classic crime of poaching rabbits on a landlord's estate. The magistrate was apparently his own uncle, and the author said nobody could be so cruel as to sentence their nephew to transportation to Australia. So her thesis was that it was a kind of early £10 POM scheme, where the uncle was simply providing assisted passage to start anew. I've always been rather sceptical of that interpretation, but it's an interesting attempt to sort of make the coercion actually consensual. But the connection with Australia has continued in that one of my sisters emigrated there a number of years ago, and my own grandfather on my father's sidetwice emigrated to Australia, but showing a certain lack of decisiveness, came back twice. So we do have quite strong links with Australia. And my parents came from various parts of,, the southern half of Britain and Ireland.

AM: What did your parents do?

GA: My father was a book publisher. He had to leave school at 18 to look after the family after his father left them. And he started in insurance and didn't like it very much, so he wrote to Mr Longman of Longman's Books and said, "I would like to move into publishing". And amazingly enough – I mean, inconceivable now -- Mr Longman gave him an interview and he got the job. So he worked for Longman's for 22 years before moving to another publisher, and that's what took him to Nigeria. He became Longman's representative in Nigeria. That was why he was there. My mother read English at Newnham and joined a graduate scheme for women set up by Unilever. However, when she got to Nigeria, she pretty rapidly concluded that it was simply glorified secretarial work. So she left and she worked in University College, now University of Ibadan, working for the VC as his secretary. And my parents met in her office when he came to the University of Ibadan to try and flog some books.

AM: I see. Right, well, that takes me back. Well, something about their character. I mean, people are strangely reluctant to talk about their parents' character often, but were they encouraging and warm and imaginative or horrid?

GA: They were extremely nice. My mother was, I think, quite a nervous person, but was an enormous emotional support. My father was a slightly more distant... is a slightly more distant person, but enormously enthusiastic about certain things. So I definitely think the reason I became interested in history is that he used to talk about history at the breakfast table or any other table. So when, for the first time, a teacher said ‘we will have a history lesson,’ my ears pricked up. It was the first time anything really exciting had happened at school. So I knew I was going to like history before I had any idea what it was. And he was and is also a great reader. So even today at the age of 100, he is at the moment halfway through a 1,000-page biography of Maria Theresa. So I certainly got the love of history from him. My mother also read a huge amount, of course, as you'd also expect. I had many more political conversations with her growing up than I did with my father. She found it much easier to talk to people she disagreed with, I think, than my father did, at least in those days.

AM: So going back to snakes and steam engines, I didn't think there were a lot of steam engines in West Africa at that time, were there?

GA: Yes, the colonial railways were fairly extensive. And possibly the single most exciting event of my early life, Alan, was when a steam engine called the River Warri crashed through the barriers and blocked a road. And so my unfortunate father was obliged to take me to see it yet again every day until they finally managed to move it. And like lots of little boys are supposed to, I really did actually want to be a steam engine driver. I quite soon grew out of that. Whereas snakes, I was... I mean, there genuinely were quite a few, if you knew where to look. As an adult in Africa, I've hardly ever seen snakes. It's not like Australia. I mean, there are actually not that many and most of them are not poisonous. But when you're very small, the Longmans book of West African snakes had an absolutely compelling, illustration of a spitting cobra. And that really was my idea of a snake.

AM: Did you meet one?

GA: My father used to take me to the zoological gardens in Ibadan, where there was some of the most dangerous snakes in pits. I saw one or two others, but they didn't long survive the experience, because, although my father drove himself most of the time, he did also have a driver from southeast Nigeria, who had a fantastic eye. And I remember us returning with the driver at the wheel, parking in front of our house. And over the entrance, there was an entanglement of green, one might say. And the driver looked up, picked up a stone, threw it, and then there was the sound of a snake falling down, dead, hit just behind the neck. And he did the same to other snakes. In i a different era, he could have been a professional sports person, I feel, instead of which my father lost contact with him after a letter saying he was going home to join the Biafran army.

AM: Right, well, moving on, your first school was in..?

GA: My first school was actually the senior staff infant school of University College of Ibadan, where I was for two years.

AM: Was it mixed colour-wise?

GA: Yes, it was, yes. And it was also...there were boys and girls and Nigerians; mostly Yoruba and expats. I enjoyed being there. I don't remember very much except for a fire in the grounds that was particularly exciting, because a whole lot of snakes were escaping from it. But it gave me, I suppose, a slightly positive view of school. I think that's the main thing I can say about it.

AM: And then, moving on, at what age did you leave ?

GA: We left when I was six and I went to a convent school in the Sussex village of Storrington, because of my parents. They did live in London briefly, though I don't remember that at all. They then moved to Sussex.

AM: So you came back to England when you were six?

GA: Yes. I had been there on leave before, but I don’t have any memories of England until the age of six. We arrived .just in time for a famously cold winter. .. I think it was, it must have been about 62,-63.

AM: That's right, it was 62-63. I was in Oxford and it was very cold.

GA: It started snowing, as far as we were concerned, on Boxing Day and it just was white for months and months after that. So I got a quite misleading idea of how cold this country is most of the time. Yes, I went to the local convent for a couple of years, as did the elder of my sisters with whom I used to walk to school.

AM: Did this instil a deep love of religion?

GA: Not really. I don't think I really enjoyed that school, though I didn't dislike it either. But, I mean, for one thing, it was Catholic and my parents were both Protestants. I remember my mother being outraged to discover that the nuns were teaching us about purgatory, which of course is not a Protestant belief. Although generally they had separate sessions, I don't think they were services, but there was a separate session for the Protestant children while the Catholics were having their service. Everybody was either Protestant or Catholic, there was nobody else. But I guess it was a reasonable school. I then went to prep school in Worthing for five years, which I didn't enjoy, though I don't think that's the fault of the school. I was just at an age when having teachers telling you what to do all the time was quite galling.

AM: You were a boarder?

GA: No, it was a day school and I came on the bus.

AM: No cruelty? No bullying?

GA: No, I do seem to remember I was involved in a lot of fights, but I don't actually think there was much damage done. And I had a very strong sense that it's very important to stand up to bullies, whether on your own account or on somebody else's account. That was a big part of how I saw the world when I was that sort of age. But I actually don't think it was a particularly violent school and there was no corporal punishment in any of the schools that I attended. I went on to secondary school: Sevenoaks School in Kent. There I was a boarder and actually it really wasn't at all like the stereotypes. I think one theory might be that it was partly because. there was quite a lot of supervision of prefects. So one scenario in which I think bullying happens is when older children have got free reign, perhaps as in the 'Lord of the Flies', which is too much of a generalisation, but in any case on the whole there was a very, we would now say supportive culture. So it was actually a place I found hugely more interesting than my previous educational experience. And I was pretty happy to be there. It was full of interest.

AM: We'll come back to it because I omitted to ask you a question. I came back when I was five from India and I often sort of date my anthropological interests from the culture shock coming from the remote part of the Raj and the Empire back to an equally cold winter in 1947. But it was the learning the customs and culture and then at boarding schools, which I think gave me a sense of relativity that this wasn't in the blood. I had to learn it and perform in the Western ways. When you came back at age six did you get any culture shock that you can think of?

GA: I think I must have done, but I must say if there was it wasn't all that severe Much later I had a girlfriend who had spent time when she was very little in I think what is now Zambia and therefore she had at that time quite a strong Southern African accent. And so she was picked on at school for that reason. Whereas I didn't have that experience. I mean partly that there was no such thing as a distinct colonial accent in West Africa. There weren't enough, which reflects the nature of the colonialism there. There weren't enough Europeans for that to be a linguistic possibility probably.

AM: Okay, well coming back to Sevenoaks, presumably you streamed towards the end. What subjects did you gravitate towards? I assume history, but I don't know.

GA: Yeah, I did think, but not for very long, about doing sciences. But in the end, for A level under the traditional English system of choosing three A level subjects, mine were definitely History, definitely English and I would have loved to do economics, but because of a timetable clash I did Business Studies instead. Which actually was quite interesting in that it did provide introductions to little bits of social psychology for example and organisation theory that I wouldn't have done in economics, and the economics I learnt later anyway. So that although I was slightly resentful at the time at having to settle for what I considered a poor fourth choice, actually it was quite empowering as we would later say.

AM: Were there any teachers who you found particularly inspiring or helpful?

GA: Absolutely, yes, I was incredibly well taught. There were English teachers who were wonderful at making one realise how exciting what one was reading was.

AM: Do you remember any of their names?

GA: One of them was Mr. Hennessey, he was one of a number of teachers who were extremely inspiring about English literature. But he actually supervised my first dissertation which arose because the English language O level syllabus had an option where you could write an extended essay and he suggested I might write a fiction. I was flattered to be asked but I thought I'll stick with what I had first thought of. So it was actually an argument for why there was the case for a united Europe. And that was one of the earliest things that interested me politically. I don't know what he personally thought, but he was an extremely good supervisor on that and sort of asking me questions to think through what I thought. The business studies and economics teacher, Casey McCann, was a very charismatic Irishman who made lots of funny jokes, but also he advised me to do politics. He was very keen that I should go to the LSE to study politics. But I learnt a huge amount from him. He was also an inspiring individual I would say. He eventually became a head teacher in Brazil. And I saw him not too many years before he died. I think he died out there. And then for History, there were a whole bunch of teachers all of whom differed from each other greatly in their style of teaching but in their different ways were all extremely good. So they were very encouraging and I really was incredibly fortunate in my secondary and particularly A-level tuition.

AM: One of the things that happens to some people anyway, to me, at about the age of 15 or 16 is that you are confirmed into the Church of England if you are C of E. Or even if you are not, quite a lot of people go through a kind of religious phase in their middle or later teenage years. Did that happen to you?

GA: Yes, I was indeed confirmed in the C of E. I was keen but without, in those days, enjoying services. I was always looking at my watch and counting how many pages of the service sheet were past. But I did regard it very much as a matter of a personal relationship with God. And there came a point in my 20s when I felt I didn't really have one. So that was a point when I didn't become an atheist but I genuinely wasn't sure what I believed. Which has pretty much continued though partly because of marrying a very committed Anglican I have continued to go to church from time to time. And I like the Church of England., I think there is a lot of intellectualism at the higher levels of it. There are lots of very thoughtful priests. So I am perfectly happy to call myself an Anglican these days, I must say. There was a phase when I would have said I was agnostic. On the whole now I would describe myself as an Anglican. But in a way the things that I most appreciate about the Church these days are not what attracted me to it as a teenager, which was very much the personal relationship which of course as we know is doctrinally central both to Christianity in general and to Protestantism in particular. But these days I love the ritual. Yes, there has actually been a kind of inversion in what I think about it.

AM: Interesting. The other two things that... Well, two of the things that are important in boarding schools. One is sport - games. Did you play and were you good at any sports?

GA: I was very enthusiastic. I was reasonably good at rugby and soccer and hockey. But while I was recovering from a broken collarbone, sustained while playing rugby, I discovered I was best at long-distance running, which the school actually regarded as one of its three major sports. So after that I switched my focus to cross-country running. I suppose I was at one time the second best runner in the school. I was never the best. But it was a team event and I much enjoyed the team aspect. But I must say for me the biggest, the most emotional sporting thing was house competitions against other houses where you played every sport. I am sure it wouldn't surprise you. There is a strong sense of solidarity with members of your house, particularly in the boarding houses, who tended to do disproportionately well in relation to their numbers because of their extra commitment.

AM: Another thing that also occurs at that time is either an interest or non-interest in music. Has music been important in your life?

GA: It's always been part of my life. Not as important as for some people. But I suppose in my teens, 20s and 30s, I did spend an awful lot of time listening to a rather small number of singers, above all Bob Dylan, who I used to listen to in Ghana, for example. I'd have a particular LP at the time, a particular album which would obsess me for a few months and then I'd move on to a different one. And I always enjoyed some elements of classical music, but my parents were huge opera fans, which actually I think did slightly deter me. That was one area in which I slightly rebelled. I wasn't as enthusiastic, though nowadays, I think opera's fantastic, but in my teens I was more interested in particular kinds of pop music. [At Cambridge] I remember Christopher Ricks, of course, giving his, I think, possibly annual lecture on Bob Dylan, which was very interesting.

AM: And the last thing, did you have any particular hobbies or passions that you really loved doing around that age?

GA: I had an unhealthy interest in war games. I spent quite a lot of time playing, not so much Risk, which I regarded as a slightly inferior game because of the strong element of chance, but more Diplomacy, which has no dice, and also Avalon Hill war games. And I only gave those up really when life became too busy, but for a long time...

AM: At what age was that? When did life become too busy?

GA: I think possibly when going to the LSE to teach.

AM: So, you were 14 to your mid-20s?

GA: Yes, although by then, instead of playing regularly and with a lot of people, it was down to just occasional weekends with a particular friend. But in fact, my first publication was in a Swiss magazine, and it was a defence, it was a Russian defence for a game called Stalingrad, which would have been better called Barbarossa because it was the German invasion. And I was supposed to be playing by post with this Swiss guy, and I think he couldn't perhaps work out how to get through the defence, so he decided to publish it instead. So he never actually played the game, but that was my first publication, I'm slightly embarrassed to say.

AM: So, moving on, you came to Clare College, Cambridge, to read history?

GA: Yes.

AM: And were there any teachers here, or lecturers, who particularly influenced you or inspired you?

GA: Charles Parkin was our Director of Studies, and he was, as he would quite often comment, a Northern Grammar School product. I think he did go to Manchester Grammar School. He was an incredibly dedicated Director of Studies who was extremely close to his students and who I respected enormously. In contrast, the best-known historian in Clare was Geoffrey Elton, who would affect not to remember who the Director of Studies was on the grounds that he hadn't published very much.

AM: Did you know Geoffrey?