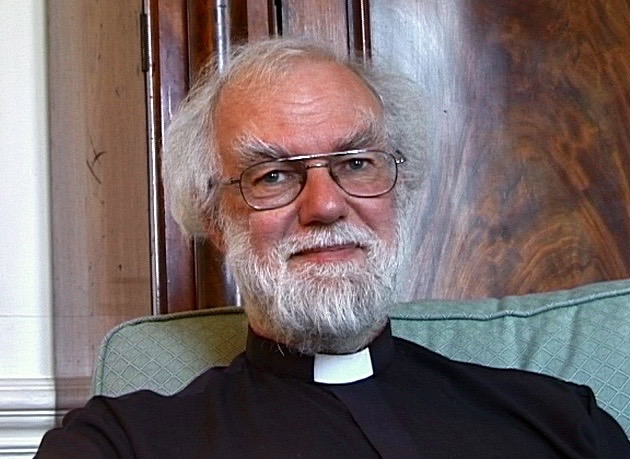

Rowan Williams

Duration: 1 hour 24 mins

Share this media item:

Embed this media item:

Embed this media item:

About this item

| Description: | An interview of Dr Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury, on 1st July 2015, filmed by Alan Macfarlane and edited by Sarah Harrison |

|---|

| Created: | 2015-08-31 09:28 |

|---|---|

| Collection: | Film Interviews with Leading Thinkers |

| Publisher: | University of Cambridge |

| Copyright: | Prof Alan Macfarlane |

| Language: | eng (English) |

Transcript

Transcript:

Rowan Williams interviewed by Alan Macfarlane 1st July 2015

0:05:07 Born in Swansea in 1950; my mother's family on her mother's side had been in the Swansea valley in the same village for about a century and a half; Ystradgynlais was the family home; before that, the family had come from over the border in Carmarthenshire, just over the other side of the Black Mountains; my mother's father was a Pembrokeshire man from somewhere round Haverfordwest; he migrated to the Swansea valley and arrived only speaking English and had to learn Welsh; my father's family were mostly from the upper Swansea valley but some from the upper Rhondda; on the whole my mother's family were farmers and farm labourers, my father's were miners so when my father married my mother the two families didn't entirely get on; there was a certain social distance between them, farming was a little more respectable as was shop-keeping, and my mother's immediate family were shop keepers; my father's eldest brother worked for my mother's uncle on a farm as a casual labourer for a while, and that hadn't been a happy experience; they were not from educated backgrounds; my mother's eldest sister had gone to college and trained as a teacher, but apart from that nobody had anything resembling higher education; the only grandparent who survived into my childhood was my mother's mother; my father lost both his parents when he was very young and was basically brought up by his eldest sister, which was not uncommon in those days; my father's three unmarried sisters and one unmarried brother lived together and I remember it as a very noisy household, with a very powerful personality, my father's oldest sister, dominating; she had had a rather bad accident and couldn't walk very well and tended to sit around with her leg up, barking orders at the family; she was very formidable; my mother's mother was very typical valley, chapel, middle class..they were all chapel but not devoutly so

4:00:13 My mother was one of five but was brought up as an only child by an aunt; I have never quite understood this, but when she was very small she went to live with her mother's sister and went to a convent school, which was extremely unusual; it may be that my grandmother felt that she was have move opportunities if she lived with Auntie Polly; it was a king of fostering, and I don't think that was uncommon; people talk about the timeless fixed patterns of families in village life; actually, my recollections were of chaotically complicated relationships sometimes; so my mother had had a bit more education than the rest of the family, apart from her eldest sister, and when she was young I think had some aspirations to be a bit more of a professional; she was a very good pianist; I can remember her when I was young as a very forceful, energetic, performer on the piano - classical; my father was probably saved from the mines by the war; he served in the RAF, trained as an engineer, and so at the end of the war he had some opportunities that others hadn't had; he was in France for a bit but he hardly ever talked about it; he eventually went into what was then the Ministry of Works and designed heating and lighting systems for public buildings; my mother was very emotional, very extrovert, and loved to be the centre of social things, and loved entertaining; my father was very subdued, quiet and private

6:33:11 I first went to school in Cardiff; we had moved away from the Swansea valley when I was about four for my father's work; because I had had a rather complicated health record as a small child I was sent to a little private school in Cardiff; I had meningitis when I was two and that took a while to clear up, and I was also very prone to bronchitis and things like that; I think they thought that my nerves wouldn't stand up to an ordinary primary school; my very first memory I think would be the National Eisteddfod in about 1954; when the National Eisteddfod comes to town its a great event, and I can just about remember that week when something was going on that was very important; there were people talking about singing competitions, and I remember a circus procession in the village street about that time also; another memory at about the same age was one Christmas when it snowed and footprints in the snow in the back garden; I think that because I was a rather sickly child I was never any use at sport and didn't try very hard, so as far as hobbies were concerned it was really just reading; I was an obsessive reader, partly because I spent quite a lot of time in bed and that was a way of passing the time; I am short-sighted, but I don't think I wore glasses before I was eleven or twelve

9:18:06 The private primary school operated out of a suburban house in Cardiff; it must have only taught a few dozen children; I remember it very much dominated by the personality of the head teacher, a very old-fashioned spinster; we were encouraged to read and learn poetry; I took the 11+ but at that time we were moving house again as my father's job had taken him back to Swansea, so I went to secondary school there [Dynevor School]; it was a bit of a rude shock because it was a very large state school in a town I didn't know with people I didn't know; it was pretty gruelling and I was bullied; it was a boys' school only so there were all the rituals of bullying and I think I must have been a very bulliable boy; that being said, but the time I left that school I was deeply in love with it and am still in touch with my school friends from those days; I think we all agree that we had an extraordinary education of the old-style Welsh grammar school variety; I think that there was quite a strong sense in most of these schools that if a child showed signs of real interest in something you encouraged them; you would lend them books, give them time, and that is a large part of my memory, of teachers taking time beyond hours, to talk, suggest and advise, with what seemed endless availability; by the time I went to secondary school I was already interested in church, the Bible, thinking that when I grew up I might be a Minister; I don't know how it happened as my parents were not particularly committed; we went to chapel and I went to Sunday school, but it wasn't pushed at me at all; I think that at some time something just caught me, probably at about eight or nine; I had found already by grammar school an interest in history, drama and literature were pretty well formed and the school looked after them very well; between nine and twelve I read fantasy, was fascinated by mythologies, but I didn't read C.S. Lewis until later; Tolkien hadn't come out then; I liked historical novels, but classic children’s fantasies, E.M. Nesbit especially; I enjoyed 'Puck of Pook's Hill' especially; I liked, and still like Kipling; I remember the 'Jungle Books' very vividly, but 'Puck of Pook's Hill', which I must have read when I was about ten, made a big impact; I didn't read a lot of poetry at that time; I enjoyed it but it was not a major interest; it became more so from twelve or thirteen onwards; 'Puck' described an integrated world in which nature and the spirit world are interconnected; I felt that that particular aspect of 'Puck' and other fantasies, suggesting something other just round the corner of the routine world, continue to be deeply formative, and I guess had something to do with my faith as well; I used to sing very regularly, drama increasingly, and the Debating Society with the first bits of political education; then in the sixth form there was a lot of encouragement to develop into a joint society with the girls' grammar school up the road, which was vastly popular; we had a very gifted, warm and imaginative drama teacher who built up extra-curricular things which developed into the inter-school society, which was unusual; so we had not only a school debating society but an inter-school debating society and a discussion group, and we produced plays and performed concerts together; looking back I think we were hugely fortunate in that background assumption that everything was capable of being talked about, that arguments didn't kill you, that the world of the imagination was to be taken as seriously as anything else; a lot of that is down to that particular teacher and one or two of his colleagues; his name is Graham Davis and he is still alive; there were other teachers who inspired; the teacher who started me off with Latin at about thirteen was one of those who was prepared to give huge amounts of time, to lend books and discuss; I think he was one of the first teachers in Wales to introduce Russian into the curriculum; I didn't study it with him because our options were a bit limited, but he knew I was interested and we would talk about it; he lived not far from me so we managed to chat on the bus sometimes; also there was a very good English teacher in the sixth form who pushed, nourished and encouraged; on writers that interested me, Shakespeare goes without saying though Milton did not capture me at that time; we had a very interesting selection of poets for 'O' levels and that is when I discovered Thomas Hardy; I have never been a great lover of him as a novelist, but as a poet I take him very seriously indeed; so did Hardy, Frost, Edward Thomas and Yeats, all of whom dug themselves into my mind; that was perhaps when poetry began to matter seriously; I do remember one particular essay that was set for us on love and death in Thomas Hardy's poetry; my first reaction was that I hadn't got a clue what it was about, then reading and re-reading four or five of the poems and a light going on in my brain, and thinking that I really understood what the question was about; I wrote a rather impassioned essay on the subject and I still have the exercise book with the teacher's comments, and he liked it

20:42:10 I was Confirmed, but the more important turning point was a year or two earlier, after we had moved back to Swansea when we stopped going to chapel and started going to church; that was partly because the local chapel was a bit dull and the local church was not; I was twelve at the and I think I started the ball rolling; I simply got up very early one Sunday morning and went on my own to the parish church, leaving a note for my parents; when I came back and told them it was really nice, they came with me the following Sunday and we all agreed it was better than chapel; we were fortunate in having a parish priest who was the most wonderfully creative and supportive person; it all sounds very positive, but I just feel I was very fortunate that the teachers and mentors I had in my teens were so encouraging; this particular parish priest spent altogether about a quarter of a century in the same parish, and never looked for higher office; he was very well-read, unexpectedly interested in politics and so on; he again gave his time very patiently and generously to us youngsters, and when many years later at his funeral I met somebody who had been in the choir with me, she said that she hoped that our children would have somebody who would be for them what Eddie was for us - an adult who wasn't your mum or dad, who was just a little bit unconventional, and who never seemed to be impatient or judgemental; I did not have any crises of faith in my late teens; 'A' level English had been a very affirming kind of study; coming up to Cambridge in 1968 with what I'd felt of as an immensely nourishing diet, the odd thing was that theology at that time seemed a little bit thin compared to what I had been doing in 'A' level English and Latin; in my first year here I did wonder if I had made a mistake in doing theology because the stimulus and inspiration had been coming to me from my literary studies, that's where the "magic casements" seemed to be; elementary Hebrew didn't quite cut it in the same way; that was in the days when we had to do Greek and Hebrew in the first year; at that time I felt, especially in studying people like Hardy, King Lear, and first encounters with poets like R.S. Thomas and David Jones, that I'd been given a great deal of the spiritual bank; I read a certain amount of Chesterton when I was in the sixth form which excited me a lot at the time, though it doesn't now; at the time Chesterton's own sense of re-enchanting the environment was a powerful thing for me

26:13:15 It was a bit unusual to go to Oxbridge from that school; we frequently had one Meyrick Scholar going to Jesus College, Oxford, but it wasn't an Oxbridge oriented school; we had had family living in Cambridge so quite regularly in my early teens we would come here on holiday and I think I developed a fondness for the place; I suppose it is that kind of rather random preference that when I was asked in the lower sixth where I was thinking of applying, I said I would have a go at Cambridge; I sat the old scholarship examination and got one to Christ's to read theology; I sat the scholarship in English but with the aim of reading theology, though with a bit of a divided mind in my first year; Alex Todd was the Master; I had applied originally to St John's and was interviewed there and they passed me on to Christ's; I was interviewed by Andrew Macintosh, then Chaplain of St John's and later Dean, somebody I still see; it was ever so slightly surreal when recently I found myself in a congregation preaching to Andrew and remembering our first conversation when I was seventeen; it was a conversation which was quite important for me because he pressed me on what I was interested in within theology; I think that was when the essay on love and death and Thomas Hardy came to my aid, and told him that I was quite interested in those philosophical things and moved from there

28:43:20 The Cambridge I found was a completely different Cambridge; my uncle had lived just off Mill Road and that is not the Cambridge that people see much of; I also remember on my second or third night in Cambridge being stopped by a homeless man on the street and spending the next hour or so just walking the streets with him, finding out about another kind of Cambridge; that never left me because all through my three years I was involved with doing bits and pieces for the homeless in Cambridge; I think I was aware as an undergraduate of several Cambridges; before I came up I thought I would love to join the Union as I had enjoyed debating at school, but realized it was an all or nothing thing; the same with the ADC; so I did a bit of acting and sang quite a lot; I belonged to a little group of volunteers who went out at weekends to help at what was then the Spastics' Society Home at Meldreth; we would take the bus out on Sunday afternoon and spend a few hours playing with the children and helping the staff; I was studying hard but remember talking a lot as well; on teachers, the biggest impact was from Donald MacKinnon, undoubtedly one of the most unusual characters of Cambridge in my time, very eccentric, very complex, a very anguished personality; he was doing a course of lectures during my first year on the problem of evil and like of lot of my generation I had read John Hick's book called 'Evil and the God of Love', and been quite impressed; if you think at all about religious matters that's the kind of thing you think about; I was really swept away by Donald who took us into territory that I recognised from my sixth form English; that was a kind of click moment, feeling that actually theology is about these things; he talked about King Lear, Antigone, Marx and Hegel, and about the Holocaust, with such intensity and imaginative and moral depth; it took years before I was able to open John Hick's book again because he saw this not as a problem to be solved but something that drives you to think; when Donald was lecturing you just knew you would not get any useful notes to pass exams with, you just had to absorb his thought processes, including the long pauses when he would gaze out of the window or grab the bars of the radiator and shake them; his lectures were never dull and I went to a lot of them over the three years, and later on became a colleague and friend; a lot of us of that generation would say that Donald was one of the formative influences, and one of the influences that allowed things to be difficult; don't gloss, don't look for easy formulae or quick solutions; there are times when I think that it can be almost self-indulgent, and times when Donald was dangerously near that edge, just revelling in the shere moral awfulness and complexity of it, yet I wouldn't have had it otherwise; he just made sure we didn't have easy answers; when I read about Wittgenstein saying to a colleague "Go the bloody hard way", I thought of Donald; also he was one of the relatively few people in Cambridge at the time who was really keeping abreast of continental philosophy, who in the sixties and seventies was telling us we needed to come to terms with Gadamer and writers like that; he would read continental philosophy far more deeply than others and just pass that on

34:39:10 I was aware of the student unrest in 1968; I think that in the last couple of years at school we were all very conscious of large global questions; in my lower sixth year I was part of a little group who spent two weeks in North Wales at a conference which the United Nations Association had organized for school students; there must have been a hundred or more of us, and we had a fortnight of lectures and seminars on development issues, global conflicts of various kinds, and it was very intensive; I met my first ever Chinese student, also somebody who had spent a year doing voluntary work in Bolivia and had sat out a revolution; we had a frank exchange of views with somebody from the South African embassy, and one of the things I remember was that rather rashly he had distributed a little pamphlet the night before; I had become friendly with a young man from another school in Carnarvonshire and we sat up late looking through the pamphlet; my friend pointed out that 25% of children apparently received free education, but that meant that 75% didn't (he is now a QC); I remember the following day after the presentation John getting up and saying that according to their own statistics 75% of African students did not receive free education, and from that I learnt something about politics and rhetoric; however the Paris événements de Mai did not impact a lot, except that a month or two before I went up to Cambridge I and a group of friends went to Taizé the religious community in the south of France for a week; Taizé then as now organized large conferences for young people all around Europe, and it was a great experience meeting European students, including some who had been in Paris in May; suddenly we were only a handshake away from these events and hearing a bit about what it had been like and what the issues were, and struggling in awful French to discuss these questions; that was in the background when I started here but probably during my time in Cambridge my politics were a bit vague; I was a bit more interested in direct social service questions because those were the issues that presented themselves; it took me a while to formulate where I was politically and it helped a lot that one of my friends gave me as a 21st birthday present a volume of George Orwell's collected works; when I read that I thought I knew where I belonged; I am a great fan of Orwell, though not uncritical

39:06:13 I was taught by John Riches who was then Chaplain of Sidney Sussex who has been a professor in Glasgow for most of his later career, and is still a friend; John must have just started as Chaplain and I must have been one of his first students; he had studied in Germany, so like Donald MacKinnon he had a bigger world to draw on; we spent our first years arguing furiously about the relative merits of Karl Barth and Thomas Aquinas; he had started reading the work of the Swiss Catholic theologian, Hans Urs von Balthasar and introduced me to his work; seven or so years later he and I were part of the first translation team putting Balthasar into English; John was a person who wanted to argue creatively and expected you to accommodate as he would, so we both felt we were moving along; I remember him very fondly and gratefully; Stephen Sykes, then Dean of St John's taught me in my third year; again a very challenging supervisor in the best possible way; undoubtedly the supervision system is one of the main strengths of Oxbridge; as much as anything it is the time taken; what you do for the supervision system is not just to write an essay and wait for comments, but ideally to argue and treat an essay as a discussion opener; I think that with most of my supervisors I found that was the case

41:13:17 After three years I wanted to do more theology and I had become very interested in Eastern Orthodox theology, having had an interest in things Russian for quite a while; in my third year as an undergraduate we had a visit from Nicolas Zernov, a great Russian émigré figure, who spoke here on the religious renaissance in early twentieth century Russian literature and philosophy; I was completely fascinated by that and read Nicholas's book on the subject and decided I'd like to explore that a bit further; nobody much here seemed to know about it but I applied to Oxford eventually and spent four years there doing a doctorate on the work of Vladimir Lossky, one of the Russian émigré thinkers of the twentieth century, putting him against the background of nineteenth century Russian thought and early Greek Christian thought, the streams that fertilized his own thinking; I knew I would have to learn Russian, but fortunately Lossky spent most of his adult life in France and published a lot in French; I learnt enough Russian to read the basic texts that he was using and to read a fair bit of some of the theologians of the generation before him, and happily discovered a real treasure trove in a whole bundle of unpublished lectures by Lossky which had been transcribed from tape recordings; I spent a good deal of my second year just working through this mound of raw material; he died quite young in his fifties so these were the last lectures that he gave and you could see how his thought was maturing; I had to refresh my Russian later when I wrote a study of Dostoevsky; because I had never learnt it as I would have liked, and never been able to speak it with any ease or confidence, I have had to refresh it from time to time; they say that languages learnt after twenty-one don't tend to go in quite as deeply unless you are using them all the time; I learnt German when I was twenty and Russian later, and I know that my German is passable, but not Russian; I have translated Rilke so my German is good enough for that and for basic conversational purposes; there was a point in my twenties when I had a German girlfriend for a while, and that helped; Donald Allchin was my supervisor; he wasn't really a specialist in things Russian but he knew a great deal about the Orthodox church; what he did for me as a supervisor was not so much academic direction but just networking, introducing me to people I should read or meet; he was terribly unsystematic and by today's standards you would say a perfectly terrible supervisor, but he did what I needed in that respect

45:13:13 In those four years in Oxford, again I was singing quite a bit, and we had a little chamber group in Wadham; again some involvement in working with the homeless and others; a little bit of drama, I played Thomas More in 'A Man for All Seasons', and also trying to keep up my interest in some other areas; in my third year my supervisor suggested I might go to the States to meet some of the Russian émigré scholars which was a very good idea indeed; but in order to pay my way he arranged that I should do some lectures at a seminary in New York on T.S. Eliot; because that was a huge and long-standing interest I was able to deliver those lecture to subsidise my trip; I sing, but am a genuinely very bad pianist; singing is one of my greatest joys; in my teens I got very interested in early music, Tudor and what little there was of Medieval; I remember in 1966 or 67 trying to adjust a very cheap transistor radio in my bedroom to get the Aldeburgh Festival for the first performance of Britten's 'Burning Fiery Furnace'; both Britten and Vaughan Williams were great inspirations; by my teens I loved the late Romantic early Modern English school; at that time I hadn't quite cracked the great central body of Bach and Mozart, but that came very quickly at Cambridge; so from Monteverdi to Mozart would be my enthusiasm in those days and probably still is; of all those, Bach without a doubt, and deeply love Mozart and know most of the 'Magic Flute' by heart; I also like the Tudor song writers, Dowland, Morley, people like that, Purcell, and as a singer you develop a particular attitude to composers; Mozart is wonderful for singers, as is Purcell, but Bach is purgatory; I did not come very often to King's Chapel, but I was singing in the choir at Christ's so that took up quite a bit of time; then there were the little groups that came and went in college, madrigal groups that I enjoyed

49:40:06 Poetry is definitely one of the numinous gateways to God; with both poetry and music you are dealing quintessentially with those bits of human operation that don't fit neatly within the preordained categories where you are not quite sure what's going on and never will be; people asked sometimes about where poetry comes from and the answer is you really cannot get at it; when you say I am now going to sit down and write a poem, you can't do it, but there are moments when you suddenly realize that you subconscious or whatever has been working on a picture, or a word or phrase or a sensation, which is beginning to nudge you; get this down, as if someone has opened a door and shouted for you to come and take dictation; I certainly find that the act of writing takes you forward; I am not one of those who can compose in my head; I do need a page, and what I need is a sense of a picture or phrase that is nudging, get that down and what comes before and after, and you gradually move out; there is a phrase in a poem by Charles Williams, C.S. Lewis's friend, where he imagines Shakespeare on the underground in London; imagines him sitting on the tube with a newspaper, hat pulled down, pencil in hand, scribbling, and he's just thought of the line of 'Merchant of Venice' "Still quiring to the young-eyed cherubims"; how on earth do you derive the rest of the play from that line, you don't know, but I thought that was a really interesting way in; there is a word, a phrase, and you think where does it belong, and you move outward and outward; I write quite a lot when I'm travelling - long train journeys, airport lounges, places that are nowhere in particular, and it does help to be quite because I want to listen; I do think poetry has to sound like something and I think it is something to be read aloud ultimately; sometimes I speak it, if I want to know where the balance lies in a line; sometimes you don't discover it, and as Auden said you don't complete it but abandon it; I find it quite difficult to edit poetry; there is a lot of correction and scribbling when you are still in the process of writing, but I find on the whole when I look at something I've done I may think it is awful but the moment for altering it has gone

54:29:14 After finishing my D.Phil. I went to Yorkshire to the College of the Resurrection, Mirfield, run by the Community of the Resurrection, a monastic community; I was still very much in two minds about my future; I had enjoyed the research and wanted to do more, I wanted to teach, I had the nagging question about what I should be doing as far as priesthood was concerned, I was also wrestling with whether I ought to be a monk; going to Mirfield, living alongside people preparing for the priesthood and doing more academic teaching and writing was quite a good holding operation for a couple of years; it was a very precious couple of years where the rootedness in the community's life did a great deal to stabilise my thinking; it left me reasonably persuaded that I offer myself for ordination in the Church of England, that it wasn't right at that juncture to try my vocation in a monastery, so when the offer came to come back to Cambridge to be ordained as Chaplain of Westcott House I said yes; because I was doing quite a lot of lecturing in those two years and not a huge amount of supervising, I had quite a lot of time to read and digest stuff and a lot of my material for my first book came from what I was working on at that time on the history of Christian spirituality; it was published in 1979 and called 'The Wound of Knowledge', a phrase from R.S. Thomas, subtitled 'Christian Spirituality from the New Testament to St John of the Cross'; essentially I boiled down a long course of lectures from Mirfield into a shorter course for Cambridge, looking at the major figures in Christian thinking about prayer and contemplation from the first to the sixteenth century; some pages of the book now make me blush because when you are in your twenties you know so much more than you do later on; some of the judgements there I wouldn't endorse now; I had read a lot but digested it very imperfectly, but it is still in print and seems to ring a bell with some people; I was three years at Westcott and then there was a lectureship in the University which I was encouraged to apply for; also at that time I wanted to ensure that I had some pastoral parochial experience so offered my services at St George's Chesterton as an unpaid curate; they happened to have a curate's house that was free so the next three years I spent living on the Arbury Estate, dividing my time doing Sunday Schools and pastoral visiting up there and teaching patristics here in the University

58:46:14 I enjoy teaching enormously; I suppose supervising one to one is very special; I think I am a reasonably good lecturer but looking back I think I probably over-stuffed my lectures in those days; I do remember a colleague tactfully saying to me once that some of his students were finding some of my stuff a bit hard-going; I remember bridling indignantly, but I realize in retrospect exactly what I was doing and I now look at my notes and wonder how they sat it out; for a couple of years I was Dean of Clare which I would very happily have stayed in for a long time; I was taken aback when I simply had a postcard one day announcing that I had been elected to the Lady Margaret Chair of Divinity at Oxford, for which I had not applied; I consulted around and went to Oxford; comparing Oxford and Cambridge, apart from the obvious things in their history and ethos - Cambridge has the more mathematical, science flavour - I have always found that Cambridge takes itself a little less seriously; there is an element of saving irony in Cambridge; that is partly because when I first went to Christ Church, Oxford, in 1971 I came to an institution that at that time took itself very seriously indeed; I developed a great affection for it when I was there as a professor later, and great affection for successive Deans, Henry Chadwick and Eric Heaton, but going there from Christ's, Cambridge, was quite a culture shock because I did feel that Christ's had a more bracing, no-nonsense, feel to it

1:02:19:08 When I moved from Oxford it was not because of a postcard, but it was still quite informal; I received a letter saying that my name was being considered as Bishop of Monmouth; I felt that if I was invited to go back to Wales I would like to, so when I was elected I said yes; I was hugely happy in Monmouth for just over ten years, three of those as Archbishop of Wales as well; then that bizarre period when everybody was gossiping about who was going to be Archbishop of Canterbury, and that my name was one but couldn't quite believe it would happen; then there was a leak in the Times; my Chaplain rang me about six one morning and suggested I took a look; apparently I had been nominated and somebody on the Crown Nominations Commission had leaked the news; it was very embarrassing as I had no notion whether it was true of not because in those days the last thing that anybody would do was to consult you about that sort of thing; however the then Archbishop of York had previously taken me aside and mentioned the Canterbury appointment and whether if I was asked I would turn it down out of hand; that was the nearest I got to consultation; it was very strange, both that period of several months when it was being discussed then a strange period of a few days when nobody could confirm or deny this story in the Times; there followed a period where a number of people actively tried to derail the appointment because I was too liberal, and as in Oxford I had been thought of as rather conservative I thought this quite odd; to be honest, it was a rather disagreeable and unpleasant time, for a whole year; it had not really registered how much venom there could be about these matters; because it was known that I had a more liberal approach to homosexuality, this for some was quite unacceptable; it had never been an issue in Wales as people knew my views, I didn't push them as I didn't think it was the Bishop's place to be a campaigner; suddenly that became an absolutely focal issue; if I were to advise a future candidate I would say that you do have to register early on that you are going to be unpopular with quite a lot of people quite a lot of the time; I don't mean that there are lots of people being consistently unpleasant, but that you become a focus for a lot of negative feeling; it is not necessarily personal but you are there to throw things at, especially in the Internet age which really got into its stride in my years as Archbishop; people don't think that there is a person at the other end and they very willingly throw a lot of mud; so be prepared for that; I say to young clergy that when you are first ordained, bear in mind that you will feature in other people's dreams and fantasies in a new way; that is even more so if you are a bishop or archbishop; then there is the fickleness of the media; you may think you have a friend or could use the media positively, it is very difficult; it is a bit like the fable of the fox carrying the scorpion across the river on its back, and the scorpion stings the fox in mid-river, apologises but says it is what he does; that is what the press does, they sting; you are never going to be in credit, stories will establish themselves quite irrespective of fact, sense, or anything else; with having to combine thought and prayer with practical administration, the only thing to do is to have a very rigorous timetable; at Lambeth Palace we had two nuns who lived on the premises and would look after the Chapel and be there first thing every morning; it helped to know that every morning the Sisters would have been there from six-thirty every morning and when I went down to say my prayers they would always be there; the day always started with that, and that was the anchor point; but balancing it out it is arguably several different jobs all at once, and you end up feeling that you are doing none of them very well; I used to get asked quite a lot to do lectures and as I wrote all my own material that was quite time-consuming; I tried to deal with as much of my correspondence personally, especially from children or young people, and that took quite a bit of time as well; then there are committees to chair, the debates in the Lords to attend, the international travel, and the rest

1:10:08:19 On the high points, there are one or two international visits which stand out; a deeply moving visit to the Solomon Islands and dedicating a memorial there to the Melanesian Brothers who had been killed in the civil war a year earlier, and that sense that I had on some of the foreign visits that that is the front line where it actually matters; later in my time there was the visit to Zimbabwe and the difficult confrontation with Robert Mugabe which was a demanding moment but quite an important one; it helped just a little bit to shift some of the pressure from the Church; in the last couple of years, not a moment, but the process of putting together an umbrella organisation for Anglican based relief and development agencies, and having the most wonderful colleagues to do that with, and a sense of pure joy in seeing that take shape and being in the right hands; that I can't describe enthusiastically enough, that was a wonderful sensation; on the bad moments, I suppose people might expect me to say the controversy over Sharia in 2008; although that was maddening, I didn't feel it personally as some other moments; I had said what I meant to say, I don't think I said it as well as I could have and there were a few days of hysteria, then it rather blew over; I didn't actually lose a great deal of sleep over it; much worse I think was the period right at the beginning when there was the controversy over the nomination of the Bishop of Reading; my friend Jeffrey John had been nominated and there was an outcry of protest right across the world because he had been in a same sex relationship, and coming to the point where I thought I would have to ask him to step down that was terrible; there were moments when I thought if it is going to be like this then I can't do it; the decisions you take that you know are damaging, know are imperfect but there doesn't seem any other place to go

1:13:18:06 On the question of evil and the role of God in suffering, I don't think there is or will be a neat answer to that; I feel my way around the edge of the problem I think by saying first of all there is a question as to whether a cost-free, risk-free universe exists; in other words, God's freedom, God's power may in some sense be constrained by what logically a world of finite events, temporal evolution, might mean; God can't do logical impossibilities; maybe if there is a world at all there has to be a world where there are risks, chance or whatever; that doesn't get you very far but it is just one small question to put in the balance; the other thing I suppose is we not only have a problem of evil but a problem of good; it is a universe in which appalling things happen, also a universe in which people are surprisingly convinced about the power and resource of grace or love or whatever, and keep going through it; if some people in the very heart of the most agonising pain and loss can sustain faith that says to me that maybe I can too without getting all the answers tied up at this stage, and I have met so many people in that position, not just as Archbishop but even before then; one of my memories from my student days is one summer doing some volunteer children's work in Bedford; I got talking with the caretaker of the school that we were spreading our sleeping bags in; he had lost a five year old child; I shall never forget listening to him talking about that, and talking with a complete lack of consolation or ease but a kind of acceptance; here was a man without any education or sophistication particularly, talking very bluntly in terms rather like Job, the Lord gives them and the Lord takes them away; I was rather in awe of that, and it is people like that, Harry Blizzard, that I think of when thinking on this problem; any account of the universe has to weigh that people like that are not being trivial or silly; so I think there is a kind of very incipient, very inchoate logical response about is there something in the very nature of finite reality, and then there is the human, emotional response, and that's about as far as it gets I think

1:18:03:14 On the fate of unbelievers, I guess that the overwhelming majority of Anglicans and probably Roman Catholics now would say that that now misconceives the problem; it is not as if God on Judgement Day looks at your form and says "Buddhist? Sorry"; my question is how does the Grace of God actually work in the lives of people outside the Christian family to produce strengths, virtues and depths that are sufficiently like what I recognise as marks of holiness for me to say that there is something there that we hold in common; for me that's to be thought through and understood as the presence of Christ, that is why I am a Christian, but that doesn't mean that I would immediately go to the Buddhist or Hindu and say that they are really Christians because they are not; whatever is working in them I can say has a family resemblance, to relate to, learn from, engage with in some way

1:19:30:10 I think that the book of mine that I am most simply satisfied with is the little study of Saint Teresa of Avila; I found it a very helpful discipline to sit, untangle and set out what I thought she was saying with the minimum of commentary and hope that it made sense and opened the door for somebody into one of the great minds of the Christian centuries; I think of all my books that it the one that I felt that I did what I set out to do; it is not a great book but is one I am pleased with; of poetry, I suppose a little group of poems I wrote which were all rather stirred by the deaths of my parents and one or two friends, a sequence called 'Graves and Gates'; it has got a poem about Rilke, others about Nietzsche, Simone Weil, Tolstoy, and then one for my mother, one for my father, and one for my dear friend Gillian Rose, the philosopher; I remember starting writing that poem on the train on the way back from her deathbed; those poems came from somewhere quite urgent; then there is a sequence in the last selection that I published which is a set of twenty-one haiku, one for each chapter of St John's Gospel; I don't know quite why that form suggested itself except that I found myself writing a haiku about one incident in St John's Gospel and then wondering whether I could do it for every chapter

1:22:11:13 I am married to a theologian; we met here in Cambridge in the late seventies and she is from a clergy family as well; we have a daughter of twenty-seven who is a school teacher in south London and a son of nineteen who is a student of English and drama in Norwich; on advising someone entering the Ministry, I should say be prepared for what it feels like to be in other peoples minds and fantasies; remember that, and then remember that ultimately you are not answerable to other people's expectations; don't ignore them but don't be a slave to them, and try to live in such a way that you prompt people to feel grateful, not only for you but what you represent, and when you preach aim at producing gratitude

0:05:07 Born in Swansea in 1950; my mother's family on her mother's side had been in the Swansea valley in the same village for about a century and a half; Ystradgynlais was the family home; before that, the family had come from over the border in Carmarthenshire, just over the other side of the Black Mountains; my mother's father was a Pembrokeshire man from somewhere round Haverfordwest; he migrated to the Swansea valley and arrived only speaking English and had to learn Welsh; my father's family were mostly from the upper Swansea valley but some from the upper Rhondda; on the whole my mother's family were farmers and farm labourers, my father's were miners so when my father married my mother the two families didn't entirely get on; there was a certain social distance between them, farming was a little more respectable as was shop-keeping, and my mother's immediate family were shop keepers; my father's eldest brother worked for my mother's uncle on a farm as a casual labourer for a while, and that hadn't been a happy experience; they were not from educated backgrounds; my mother's eldest sister had gone to college and trained as a teacher, but apart from that nobody had anything resembling higher education; the only grandparent who survived into my childhood was my mother's mother; my father lost both his parents when he was very young and was basically brought up by his eldest sister, which was not uncommon in those days; my father's three unmarried sisters and one unmarried brother lived together and I remember it as a very noisy household, with a very powerful personality, my father's oldest sister, dominating; she had had a rather bad accident and couldn't walk very well and tended to sit around with her leg up, barking orders at the family; she was very formidable; my mother's mother was very typical valley, chapel, middle class..they were all chapel but not devoutly so

4:00:13 My mother was one of five but was brought up as an only child by an aunt; I have never quite understood this, but when she was very small she went to live with her mother's sister and went to a convent school, which was extremely unusual; it may be that my grandmother felt that she was have move opportunities if she lived with Auntie Polly; it was a king of fostering, and I don't think that was uncommon; people talk about the timeless fixed patterns of families in village life; actually, my recollections were of chaotically complicated relationships sometimes; so my mother had had a bit more education than the rest of the family, apart from her eldest sister, and when she was young I think had some aspirations to be a bit more of a professional; she was a very good pianist; I can remember her when I was young as a very forceful, energetic, performer on the piano - classical; my father was probably saved from the mines by the war; he served in the RAF, trained as an engineer, and so at the end of the war he had some opportunities that others hadn't had; he was in France for a bit but he hardly ever talked about it; he eventually went into what was then the Ministry of Works and designed heating and lighting systems for public buildings; my mother was very emotional, very extrovert, and loved to be the centre of social things, and loved entertaining; my father was very subdued, quiet and private

6:33:11 I first went to school in Cardiff; we had moved away from the Swansea valley when I was about four for my father's work; because I had had a rather complicated health record as a small child I was sent to a little private school in Cardiff; I had meningitis when I was two and that took a while to clear up, and I was also very prone to bronchitis and things like that; I think they thought that my nerves wouldn't stand up to an ordinary primary school; my very first memory I think would be the National Eisteddfod in about 1954; when the National Eisteddfod comes to town its a great event, and I can just about remember that week when something was going on that was very important; there were people talking about singing competitions, and I remember a circus procession in the village street about that time also; another memory at about the same age was one Christmas when it snowed and footprints in the snow in the back garden; I think that because I was a rather sickly child I was never any use at sport and didn't try very hard, so as far as hobbies were concerned it was really just reading; I was an obsessive reader, partly because I spent quite a lot of time in bed and that was a way of passing the time; I am short-sighted, but I don't think I wore glasses before I was eleven or twelve

9:18:06 The private primary school operated out of a suburban house in Cardiff; it must have only taught a few dozen children; I remember it very much dominated by the personality of the head teacher, a very old-fashioned spinster; we were encouraged to read and learn poetry; I took the 11+ but at that time we were moving house again as my father's job had taken him back to Swansea, so I went to secondary school there [Dynevor School]; it was a bit of a rude shock because it was a very large state school in a town I didn't know with people I didn't know; it was pretty gruelling and I was bullied; it was a boys' school only so there were all the rituals of bullying and I think I must have been a very bulliable boy; that being said, but the time I left that school I was deeply in love with it and am still in touch with my school friends from those days; I think we all agree that we had an extraordinary education of the old-style Welsh grammar school variety; I think that there was quite a strong sense in most of these schools that if a child showed signs of real interest in something you encouraged them; you would lend them books, give them time, and that is a large part of my memory, of teachers taking time beyond hours, to talk, suggest and advise, with what seemed endless availability; by the time I went to secondary school I was already interested in church, the Bible, thinking that when I grew up I might be a Minister; I don't know how it happened as my parents were not particularly committed; we went to chapel and I went to Sunday school, but it wasn't pushed at me at all; I think that at some time something just caught me, probably at about eight or nine; I had found already by grammar school an interest in history, drama and literature were pretty well formed and the school looked after them very well; between nine and twelve I read fantasy, was fascinated by mythologies, but I didn't read C.S. Lewis until later; Tolkien hadn't come out then; I liked historical novels, but classic children’s fantasies, E.M. Nesbit especially; I enjoyed 'Puck of Pook's Hill' especially; I liked, and still like Kipling; I remember the 'Jungle Books' very vividly, but 'Puck of Pook's Hill', which I must have read when I was about ten, made a big impact; I didn't read a lot of poetry at that time; I enjoyed it but it was not a major interest; it became more so from twelve or thirteen onwards; 'Puck' described an integrated world in which nature and the spirit world are interconnected; I felt that that particular aspect of 'Puck' and other fantasies, suggesting something other just round the corner of the routine world, continue to be deeply formative, and I guess had something to do with my faith as well; I used to sing very regularly, drama increasingly, and the Debating Society with the first bits of political education; then in the sixth form there was a lot of encouragement to develop into a joint society with the girls' grammar school up the road, which was vastly popular; we had a very gifted, warm and imaginative drama teacher who built up extra-curricular things which developed into the inter-school society, which was unusual; so we had not only a school debating society but an inter-school debating society and a discussion group, and we produced plays and performed concerts together; looking back I think we were hugely fortunate in that background assumption that everything was capable of being talked about, that arguments didn't kill you, that the world of the imagination was to be taken as seriously as anything else; a lot of that is down to that particular teacher and one or two of his colleagues; his name is Graham Davis and he is still alive; there were other teachers who inspired; the teacher who started me off with Latin at about thirteen was one of those who was prepared to give huge amounts of time, to lend books and discuss; I think he was one of the first teachers in Wales to introduce Russian into the curriculum; I didn't study it with him because our options were a bit limited, but he knew I was interested and we would talk about it; he lived not far from me so we managed to chat on the bus sometimes; also there was a very good English teacher in the sixth form who pushed, nourished and encouraged; on writers that interested me, Shakespeare goes without saying though Milton did not capture me at that time; we had a very interesting selection of poets for 'O' levels and that is when I discovered Thomas Hardy; I have never been a great lover of him as a novelist, but as a poet I take him very seriously indeed; so did Hardy, Frost, Edward Thomas and Yeats, all of whom dug themselves into my mind; that was perhaps when poetry began to matter seriously; I do remember one particular essay that was set for us on love and death in Thomas Hardy's poetry; my first reaction was that I hadn't got a clue what it was about, then reading and re-reading four or five of the poems and a light going on in my brain, and thinking that I really understood what the question was about; I wrote a rather impassioned essay on the subject and I still have the exercise book with the teacher's comments, and he liked it

20:42:10 I was Confirmed, but the more important turning point was a year or two earlier, after we had moved back to Swansea when we stopped going to chapel and started going to church; that was partly because the local chapel was a bit dull and the local church was not; I was twelve at the and I think I started the ball rolling; I simply got up very early one Sunday morning and went on my own to the parish church, leaving a note for my parents; when I came back and told them it was really nice, they came with me the following Sunday and we all agreed it was better than chapel; we were fortunate in having a parish priest who was the most wonderfully creative and supportive person; it all sounds very positive, but I just feel I was very fortunate that the teachers and mentors I had in my teens were so encouraging; this particular parish priest spent altogether about a quarter of a century in the same parish, and never looked for higher office; he was very well-read, unexpectedly interested in politics and so on; he again gave his time very patiently and generously to us youngsters, and when many years later at his funeral I met somebody who had been in the choir with me, she said that she hoped that our children would have somebody who would be for them what Eddie was for us - an adult who wasn't your mum or dad, who was just a little bit unconventional, and who never seemed to be impatient or judgemental; I did not have any crises of faith in my late teens; 'A' level English had been a very affirming kind of study; coming up to Cambridge in 1968 with what I'd felt of as an immensely nourishing diet, the odd thing was that theology at that time seemed a little bit thin compared to what I had been doing in 'A' level English and Latin; in my first year here I did wonder if I had made a mistake in doing theology because the stimulus and inspiration had been coming to me from my literary studies, that's where the "magic casements" seemed to be; elementary Hebrew didn't quite cut it in the same way; that was in the days when we had to do Greek and Hebrew in the first year; at that time I felt, especially in studying people like Hardy, King Lear, and first encounters with poets like R.S. Thomas and David Jones, that I'd been given a great deal of the spiritual bank; I read a certain amount of Chesterton when I was in the sixth form which excited me a lot at the time, though it doesn't now; at the time Chesterton's own sense of re-enchanting the environment was a powerful thing for me

26:13:15 It was a bit unusual to go to Oxbridge from that school; we frequently had one Meyrick Scholar going to Jesus College, Oxford, but it wasn't an Oxbridge oriented school; we had had family living in Cambridge so quite regularly in my early teens we would come here on holiday and I think I developed a fondness for the place; I suppose it is that kind of rather random preference that when I was asked in the lower sixth where I was thinking of applying, I said I would have a go at Cambridge; I sat the old scholarship examination and got one to Christ's to read theology; I sat the scholarship in English but with the aim of reading theology, though with a bit of a divided mind in my first year; Alex Todd was the Master; I had applied originally to St John's and was interviewed there and they passed me on to Christ's; I was interviewed by Andrew Macintosh, then Chaplain of St John's and later Dean, somebody I still see; it was ever so slightly surreal when recently I found myself in a congregation preaching to Andrew and remembering our first conversation when I was seventeen; it was a conversation which was quite important for me because he pressed me on what I was interested in within theology; I think that was when the essay on love and death and Thomas Hardy came to my aid, and told him that I was quite interested in those philosophical things and moved from there

28:43:20 The Cambridge I found was a completely different Cambridge; my uncle had lived just off Mill Road and that is not the Cambridge that people see much of; I also remember on my second or third night in Cambridge being stopped by a homeless man on the street and spending the next hour or so just walking the streets with him, finding out about another kind of Cambridge; that never left me because all through my three years I was involved with doing bits and pieces for the homeless in Cambridge; I think I was aware as an undergraduate of several Cambridges; before I came up I thought I would love to join the Union as I had enjoyed debating at school, but realized it was an all or nothing thing; the same with the ADC; so I did a bit of acting and sang quite a lot; I belonged to a little group of volunteers who went out at weekends to help at what was then the Spastics' Society Home at Meldreth; we would take the bus out on Sunday afternoon and spend a few hours playing with the children and helping the staff; I was studying hard but remember talking a lot as well; on teachers, the biggest impact was from Donald MacKinnon, undoubtedly one of the most unusual characters of Cambridge in my time, very eccentric, very complex, a very anguished personality; he was doing a course of lectures during my first year on the problem of evil and like of lot of my generation I had read John Hick's book called 'Evil and the God of Love', and been quite impressed; if you think at all about religious matters that's the kind of thing you think about; I was really swept away by Donald who took us into territory that I recognised from my sixth form English; that was a kind of click moment, feeling that actually theology is about these things; he talked about King Lear, Antigone, Marx and Hegel, and about the Holocaust, with such intensity and imaginative and moral depth; it took years before I was able to open John Hick's book again because he saw this not as a problem to be solved but something that drives you to think; when Donald was lecturing you just knew you would not get any useful notes to pass exams with, you just had to absorb his thought processes, including the long pauses when he would gaze out of the window or grab the bars of the radiator and shake them; his lectures were never dull and I went to a lot of them over the three years, and later on became a colleague and friend; a lot of us of that generation would say that Donald was one of the formative influences, and one of the influences that allowed things to be difficult; don't gloss, don't look for easy formulae or quick solutions; there are times when I think that it can be almost self-indulgent, and times when Donald was dangerously near that edge, just revelling in the shere moral awfulness and complexity of it, yet I wouldn't have had it otherwise; he just made sure we didn't have easy answers; when I read about Wittgenstein saying to a colleague "Go the bloody hard way", I thought of Donald; also he was one of the relatively few people in Cambridge at the time who was really keeping abreast of continental philosophy, who in the sixties and seventies was telling us we needed to come to terms with Gadamer and writers like that; he would read continental philosophy far more deeply than others and just pass that on

34:39:10 I was aware of the student unrest in 1968; I think that in the last couple of years at school we were all very conscious of large global questions; in my lower sixth year I was part of a little group who spent two weeks in North Wales at a conference which the United Nations Association had organized for school students; there must have been a hundred or more of us, and we had a fortnight of lectures and seminars on development issues, global conflicts of various kinds, and it was very intensive; I met my first ever Chinese student, also somebody who had spent a year doing voluntary work in Bolivia and had sat out a revolution; we had a frank exchange of views with somebody from the South African embassy, and one of the things I remember was that rather rashly he had distributed a little pamphlet the night before; I had become friendly with a young man from another school in Carnarvonshire and we sat up late looking through the pamphlet; my friend pointed out that 25% of children apparently received free education, but that meant that 75% didn't (he is now a QC); I remember the following day after the presentation John getting up and saying that according to their own statistics 75% of African students did not receive free education, and from that I learnt something about politics and rhetoric; however the Paris événements de Mai did not impact a lot, except that a month or two before I went up to Cambridge I and a group of friends went to Taizé the religious community in the south of France for a week; Taizé then as now organized large conferences for young people all around Europe, and it was a great experience meeting European students, including some who had been in Paris in May; suddenly we were only a handshake away from these events and hearing a bit about what it had been like and what the issues were, and struggling in awful French to discuss these questions; that was in the background when I started here but probably during my time in Cambridge my politics were a bit vague; I was a bit more interested in direct social service questions because those were the issues that presented themselves; it took me a while to formulate where I was politically and it helped a lot that one of my friends gave me as a 21st birthday present a volume of George Orwell's collected works; when I read that I thought I knew where I belonged; I am a great fan of Orwell, though not uncritical

39:06:13 I was taught by John Riches who was then Chaplain of Sidney Sussex who has been a professor in Glasgow for most of his later career, and is still a friend; John must have just started as Chaplain and I must have been one of his first students; he had studied in Germany, so like Donald MacKinnon he had a bigger world to draw on; we spent our first years arguing furiously about the relative merits of Karl Barth and Thomas Aquinas; he had started reading the work of the Swiss Catholic theologian, Hans Urs von Balthasar and introduced me to his work; seven or so years later he and I were part of the first translation team putting Balthasar into English; John was a person who wanted to argue creatively and expected you to accommodate as he would, so we both felt we were moving along; I remember him very fondly and gratefully; Stephen Sykes, then Dean of St John's taught me in my third year; again a very challenging supervisor in the best possible way; undoubtedly the supervision system is one of the main strengths of Oxbridge; as much as anything it is the time taken; what you do for the supervision system is not just to write an essay and wait for comments, but ideally to argue and treat an essay as a discussion opener; I think that with most of my supervisors I found that was the case

41:13:17 After three years I wanted to do more theology and I had become very interested in Eastern Orthodox theology, having had an interest in things Russian for quite a while; in my third year as an undergraduate we had a visit from Nicolas Zernov, a great Russian émigré figure, who spoke here on the religious renaissance in early twentieth century Russian literature and philosophy; I was completely fascinated by that and read Nicholas's book on the subject and decided I'd like to explore that a bit further; nobody much here seemed to know about it but I applied to Oxford eventually and spent four years there doing a doctorate on the work of Vladimir Lossky, one of the Russian émigré thinkers of the twentieth century, putting him against the background of nineteenth century Russian thought and early Greek Christian thought, the streams that fertilized his own thinking; I knew I would have to learn Russian, but fortunately Lossky spent most of his adult life in France and published a lot in French; I learnt enough Russian to read the basic texts that he was using and to read a fair bit of some of the theologians of the generation before him, and happily discovered a real treasure trove in a whole bundle of unpublished lectures by Lossky which had been transcribed from tape recordings; I spent a good deal of my second year just working through this mound of raw material; he died quite young in his fifties so these were the last lectures that he gave and you could see how his thought was maturing; I had to refresh my Russian later when I wrote a study of Dostoevsky; because I had never learnt it as I would have liked, and never been able to speak it with any ease or confidence, I have had to refresh it from time to time; they say that languages learnt after twenty-one don't tend to go in quite as deeply unless you are using them all the time; I learnt German when I was twenty and Russian later, and I know that my German is passable, but not Russian; I have translated Rilke so my German is good enough for that and for basic conversational purposes; there was a point in my twenties when I had a German girlfriend for a while, and that helped; Donald Allchin was my supervisor; he wasn't really a specialist in things Russian but he knew a great deal about the Orthodox church; what he did for me as a supervisor was not so much academic direction but just networking, introducing me to people I should read or meet; he was terribly unsystematic and by today's standards you would say a perfectly terrible supervisor, but he did what I needed in that respect

45:13:13 In those four years in Oxford, again I was singing quite a bit, and we had a little chamber group in Wadham; again some involvement in working with the homeless and others; a little bit of drama, I played Thomas More in 'A Man for All Seasons', and also trying to keep up my interest in some other areas; in my third year my supervisor suggested I might go to the States to meet some of the Russian émigré scholars which was a very good idea indeed; but in order to pay my way he arranged that I should do some lectures at a seminary in New York on T.S. Eliot; because that was a huge and long-standing interest I was able to deliver those lecture to subsidise my trip; I sing, but am a genuinely very bad pianist; singing is one of my greatest joys; in my teens I got very interested in early music, Tudor and what little there was of Medieval; I remember in 1966 or 67 trying to adjust a very cheap transistor radio in my bedroom to get the Aldeburgh Festival for the first performance of Britten's 'Burning Fiery Furnace'; both Britten and Vaughan Williams were great inspirations; by my teens I loved the late Romantic early Modern English school; at that time I hadn't quite cracked the great central body of Bach and Mozart, but that came very quickly at Cambridge; so from Monteverdi to Mozart would be my enthusiasm in those days and probably still is; of all those, Bach without a doubt, and deeply love Mozart and know most of the 'Magic Flute' by heart; I also like the Tudor song writers, Dowland, Morley, people like that, Purcell, and as a singer you develop a particular attitude to composers; Mozart is wonderful for singers, as is Purcell, but Bach is purgatory; I did not come very often to King's Chapel, but I was singing in the choir at Christ's so that took up quite a bit of time; then there were the little groups that came and went in college, madrigal groups that I enjoyed

49:40:06 Poetry is definitely one of the numinous gateways to God; with both poetry and music you are dealing quintessentially with those bits of human operation that don't fit neatly within the preordained categories where you are not quite sure what's going on and never will be; people asked sometimes about where poetry comes from and the answer is you really cannot get at it; when you say I am now going to sit down and write a poem, you can't do it, but there are moments when you suddenly realize that you subconscious or whatever has been working on a picture, or a word or phrase or a sensation, which is beginning to nudge you; get this down, as if someone has opened a door and shouted for you to come and take dictation; I certainly find that the act of writing takes you forward; I am not one of those who can compose in my head; I do need a page, and what I need is a sense of a picture or phrase that is nudging, get that down and what comes before and after, and you gradually move out; there is a phrase in a poem by Charles Williams, C.S. Lewis's friend, where he imagines Shakespeare on the underground in London; imagines him sitting on the tube with a newspaper, hat pulled down, pencil in hand, scribbling, and he's just thought of the line of 'Merchant of Venice' "Still quiring to the young-eyed cherubims"; how on earth do you derive the rest of the play from that line, you don't know, but I thought that was a really interesting way in; there is a word, a phrase, and you think where does it belong, and you move outward and outward; I write quite a lot when I'm travelling - long train journeys, airport lounges, places that are nowhere in particular, and it does help to be quite because I want to listen; I do think poetry has to sound like something and I think it is something to be read aloud ultimately; sometimes I speak it, if I want to know where the balance lies in a line; sometimes you don't discover it, and as Auden said you don't complete it but abandon it; I find it quite difficult to edit poetry; there is a lot of correction and scribbling when you are still in the process of writing, but I find on the whole when I look at something I've done I may think it is awful but the moment for altering it has gone

54:29:14 After finishing my D.Phil. I went to Yorkshire to the College of the Resurrection, Mirfield, run by the Community of the Resurrection, a monastic community; I was still very much in two minds about my future; I had enjoyed the research and wanted to do more, I wanted to teach, I had the nagging question about what I should be doing as far as priesthood was concerned, I was also wrestling with whether I ought to be a monk; going to Mirfield, living alongside people preparing for the priesthood and doing more academic teaching and writing was quite a good holding operation for a couple of years; it was a very precious couple of years where the rootedness in the community's life did a great deal to stabilise my thinking; it left me reasonably persuaded that I offer myself for ordination in the Church of England, that it wasn't right at that juncture to try my vocation in a monastery, so when the offer came to come back to Cambridge to be ordained as Chaplain of Westcott House I said yes; because I was doing quite a lot of lecturing in those two years and not a huge amount of supervising, I had quite a lot of time to read and digest stuff and a lot of my material for my first book came from what I was working on at that time on the history of Christian spirituality; it was published in 1979 and called 'The Wound of Knowledge', a phrase from R.S. Thomas, subtitled 'Christian Spirituality from the New Testament to St John of the Cross'; essentially I boiled down a long course of lectures from Mirfield into a shorter course for Cambridge, looking at the major figures in Christian thinking about prayer and contemplation from the first to the sixteenth century; some pages of the book now make me blush because when you are in your twenties you know so much more than you do later on; some of the judgements there I wouldn't endorse now; I had read a lot but digested it very imperfectly, but it is still in print and seems to ring a bell with some people; I was three years at Westcott and then there was a lectureship in the University which I was encouraged to apply for; also at that time I wanted to ensure that I had some pastoral parochial experience so offered my services at St George's Chesterton as an unpaid curate; they happened to have a curate's house that was free so the next three years I spent living on the Arbury Estate, dividing my time doing Sunday Schools and pastoral visiting up there and teaching patristics here in the University

58:46:14 I enjoy teaching enormously; I suppose supervising one to one is very special; I think I am a reasonably good lecturer but looking back I think I probably over-stuffed my lectures in those days; I do remember a colleague tactfully saying to me once that some of his students were finding some of my stuff a bit hard-going; I remember bridling indignantly, but I realize in retrospect exactly what I was doing and I now look at my notes and wonder how they sat it out; for a couple of years I was Dean of Clare which I would very happily have stayed in for a long time; I was taken aback when I simply had a postcard one day announcing that I had been elected to the Lady Margaret Chair of Divinity at Oxford, for which I had not applied; I consulted around and went to Oxford; comparing Oxford and Cambridge, apart from the obvious things in their history and ethos - Cambridge has the more mathematical, science flavour - I have always found that Cambridge takes itself a little less seriously; there is an element of saving irony in Cambridge; that is partly because when I first went to Christ Church, Oxford, in 1971 I came to an institution that at that time took itself very seriously indeed; I developed a great affection for it when I was there as a professor later, and great affection for successive Deans, Henry Chadwick and Eric Heaton, but going there from Christ's, Cambridge, was quite a culture shock because I did feel that Christ's had a more bracing, no-nonsense, feel to it

1:02:19:08 When I moved from Oxford it was not because of a postcard, but it was still quite informal; I received a letter saying that my name was being considered as Bishop of Monmouth; I felt that if I was invited to go back to Wales I would like to, so when I was elected I said yes; I was hugely happy in Monmouth for just over ten years, three of those as Archbishop of Wales as well; then that bizarre period when everybody was gossiping about who was going to be Archbishop of Canterbury, and that my name was one but couldn't quite believe it would happen; then there was a leak in the Times; my Chaplain rang me about six one morning and suggested I took a look; apparently I had been nominated and somebody on the Crown Nominations Commission had leaked the news; it was very embarrassing as I had no notion whether it was true of not because in those days the last thing that anybody would do was to consult you about that sort of thing; however the then Archbishop of York had previously taken me aside and mentioned the Canterbury appointment and whether if I was asked I would turn it down out of hand; that was the nearest I got to consultation; it was very strange, both that period of several months when it was being discussed then a strange period of a few days when nobody could confirm or deny this story in the Times; there followed a period where a number of people actively tried to derail the appointment because I was too liberal, and as in Oxford I had been thought of as rather conservative I thought this quite odd; to be honest, it was a rather disagreeable and unpleasant time, for a whole year; it had not really registered how much venom there could be about these matters; because it was known that I had a more liberal approach to homosexuality, this for some was quite unacceptable; it had never been an issue in Wales as people knew my views, I didn't push them as I didn't think it was the Bishop's place to be a campaigner; suddenly that became an absolutely focal issue; if I were to advise a future candidate I would say that you do have to register early on that you are going to be unpopular with quite a lot of people quite a lot of the time; I don't mean that there are lots of people being consistently unpleasant, but that you become a focus for a lot of negative feeling; it is not necessarily personal but you are there to throw things at, especially in the Internet age which really got into its stride in my years as Archbishop; people don't think that there is a person at the other end and they very willingly throw a lot of mud; so be prepared for that; I say to young clergy that when you are first ordained, bear in mind that you will feature in other people's dreams and fantasies in a new way; that is even more so if you are a bishop or archbishop; then there is the fickleness of the media; you may think you have a friend or could use the media positively, it is very difficult; it is a bit like the fable of the fox carrying the scorpion across the river on its back, and the scorpion stings the fox in mid-river, apologises but says it is what he does; that is what the press does, they sting; you are never going to be in credit, stories will establish themselves quite irrespective of fact, sense, or anything else; with having to combine thought and prayer with practical administration, the only thing to do is to have a very rigorous timetable; at Lambeth Palace we had two nuns who lived on the premises and would look after the Chapel and be there first thing every morning; it helped to know that every morning the Sisters would have been there from six-thirty every morning and when I went down to say my prayers they would always be there; the day always started with that, and that was the anchor point; but balancing it out it is arguably several different jobs all at once, and you end up feeling that you are doing none of them very well; I used to get asked quite a lot to do lectures and as I wrote all my own material that was quite time-consuming; I tried to deal with as much of my correspondence personally, especially from children or young people, and that took quite a bit of time as well; then there are committees to chair, the debates in the Lords to attend, the international travel, and the rest