Philippe Descola Interview

Duration: 1 hour 48 mins

Share this media item:

Embed this media item:

Embed this media item:

About this item

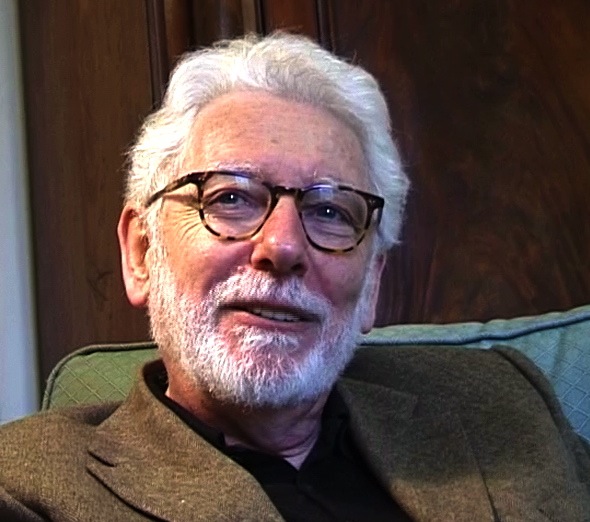

| Description: | Interview of the French anthropologist Philippe Descola on 3rd February 2015 by Alan Macfarlane, edited by Sarah Harrison |

|---|

| Created: | 2021-08-13 17:26 |

|---|---|

| Collection: | Film Interviews with Leading Thinkers |

| Publisher: | University of Cambridge |

| Copyright: | Prof Alan Macfarlane |

| Language: | eng (English) |

Transcript

Transcript:

Philippe Descola interviewed by Alan Macfarlane 3rd February 2015

0:05:07 Born in Paris in 1949; my father was a historian and my paternal family came from the Central Pyrenees; my grandfather was a medical doctor, his father was a journalist, and my great aunt was a novelist; on the maternal side, my mother was the daughter of an army officer who died young, and he came from a military family; I was brought up in a family of the classical French Catholic bourgeoisie; we lived near the Tuileries in Paris; my father saw himself as Catholic but was not really practising as such; my mother probably had a deeper faith, and I was brought up a Roman Catholic, became agnostic, and was an atheist by about ten or twelve; this was not a problem for my family who were not trying to bring me up in any particular faith; in contrast with other anthropologists who tend to belong to minority faiths, I was raised in a straight-forward way; I went to the Lycée Condorcet which was one of the elite schools in Paris

3:22:21 My father was a brilliant man, a good conversationalist and very charming; he specialized in the history of South America and Spain although he had begun by working on St John of the Cross during a time when he was attracted towards mysticism; he always left me to do what I wanted; I had a very happy childhood; I lived surrounded by books any of which I could read, and I read a large part of the family library early on; there were many pictures and my paternal grandmother was a painter and so was her father; my parents loved music so I was introduced to it very young; my mother was a social worker, a working woman, and I was mostly left to do what I wanted; I have an older sister, thirteen years older, who was in fact the person I was closest to because my parents were not at home most of the day; I still am very fond of her; so I had a very agreeable childhood in the centre of Paris which I really loved; very early on I was allowed go wherever I wanted so I explored the city; I think my earliest memory is of the Pyrenees where we would go in the summer, although the family house had been sold during the Great Depression; we would go with my grandparents, and my earliest memory was the commotion when my parents thought that I was lost at a fair in the village of Seix in Ariège; it is a beautiful place from where you can walk up the mountains and over to Spain, which I did several times later with my parents and grandparents; my grandfather was an ophthalmologist, very well educated and erudite, knew Latin and Greek, and helped me with my essays; he also knew a number of modern languages which he never spoke; he was very proud and did not want to be accused of speaking like a hotel porter; he was also a very good naturalist, so when we walked together he would tell me the names of flowers; at night he would tell me the names of the constellations and their connection to Greek mythology; thus I was immersed very early on in the written word, the classical world, and a liking for the natural world and walking, and the connections between them; I think I must have been about five when I remember my parents fear that I was lost; I think I was watching some sort of show; among hobbies, I liked making scale models but also model theatres in shoe boxes, but my main pursuit was reading, and also drawing and painting; however, from an early stage I remember feeling that I was an observer rather than being absolutely involved in what was going on; this is one of my earliest impressions of the relationship I had with the world; it was amplified by an early ethnographic experience; when I went to the Lycée Condorcet at about ten, I was not a very good pupil to begin with; I had good marks in French and Latin, but not so good for the rest; my English teacher told my parents that I wasn't doing too well so they decided to send me to an English boarding school; the end of the French term was mid-June, a month earlier than in England, so I would go from the beginning of May, by agreement with the Lycée, to the end of July, to a rather decrepit Public School in Gloucestershire called Leckhampton Court; it was a remarkable experience; the school was in an old manor house, set up by the Headmaster, and it disappeared when he retired; I went to see what had happened to it some years ago and it is now a retirement home; in this school I discovered it was the absolute opposite to the French system; the Lycée, though I was not a boarder, was very military in its organization; it was devised by Napoleon as an elite form of schooling for the French nation, based on the Jesuit system, whereby we were extremely controlled and there was no leeway for personal initiative; what I found quite extraordinary in the English system was that we were living in an area of this manor house and never saw any adults; discipline was enforced by the prefects which was extraordinary for me; it was not far from Cheltenham in very nice surroundings, so I enjoyed that; I was never bullied; I have never been keen on team sports which is another aspect of personal distance; I did some fencing, and thanks to my sister who was a fanatic horse rider, I learnt to ride early on; these I enjoyed; I played football for a while because I had to but didn't enjoy it; in France one generally had to go quite far to sports' grounds; some keen friends did, but I did not; this first experience of another system was informative, not yet to become an anthropologist, but to enjoy the diversity of the world; I began to be a better pupil later on when there was more liberty of freedom in how we learnt, and that was in the last three years at the Lycée; my parents allowed me to travel, and my first experience was to go to Canada where my father had a friend who ran a mink farm, north of Quebec; I spent several weeks there working; I must have been about seventeen at the time; I then took a boat going from Quebec to Chicago via the Great Lakes, so went to the United States for the first time; it was the time of the riots in the ghettos of Newark and Chicago, and I was struck by the violence of this society; the National Guard, patrolling with guns and letting loose the dogs, which was something I had never seen in France; of course, France had done so in Algeria but I had been too young to know that; in fact I found out what had been going on in Algeria while I was at school in England; there was a television room for the pupils and we were watching the news; I was too young to read the newspaper and these were things that were not discussed at home; we also had no television at home; the year after the Canada visit I went to Turkey, Iran, Northern Syria, all on my own; looking back it is incredible but all our generation did these things; we could travel very far with little money and we thought the world was open for us; there was probably some neo-colonial covert ideology in that in the sense that nothing could happen to us; in my family among the books was a magazine series 'Le Tour du Monde', the equivalent to 'National Geographic' at the end of the nineteenth century; there were items by geographers and proto-anthropologists of travels in different parts of the world, illustrated with etchings in black and white; I was fortunate enough to have early editions of Jules Verne illustrated by the same persons, so there was a porosity for me between novels and the accounts of travel in faraway places; when I started travelling in the Near East it was as though some of these illustrations had come alive; I remember waking in a bus in Central Anatolia and seeing the minarets in a village and a caravan of camels, and I really had the impression that I had entered into one of those etchings; so very early on I had enjoyed spectacle of the world and its diversity; intellectually at that time I loved the French language and writing, and had got good marks in that domain since I was very young; now in 1967-8 I became politically conscious; with many of my friends, we were curious of everything - of the counter-culture in the United States, of new ideas, and at the time the main place where our political conscience was forged was the 'Committees Vietnam'; it was at the level of the Lycée, where we would protest against the Vietnam war and organize demonstrations; this is where we became conscious of the iniquity of imperialism and class although I had never suffered from any oppression myself; until the mid-seventies the Lycée was the preserve of the middle-class, so a minority of people would study for the Baccalaureat and go to university; when faced with the choice of studies at university I decided with some schoolmates to prepare for an elite school the École normale supérieure; it may appear bizarre from the fact that I was drawn towards leftist politics, but at the same time we were conscious of the complexity of the social and political situation which required a keen analytical mind; that we needed to exercise our brains as criticism of the situation required intelligence and knowledge; at the time some thought we should embed ourselves with the workers in order to preach revolution; we thought that, rather that to do so, we ought to acquire the intellectual instruments of criticism required to change the system; after the Baccalaureate I entered the classe préparatoire at the Lycée to prepare for the École normale supérieure; usually you prepare over two years, it is a highly competitive system where you are accepted on the basis of your marks at the Baccalaureate; between the subsequent first and second year, only about 30% of the class remain, and at the end of the second year there is a competitive examination for the entrance to École normale supérieure; about one in forty get accepted; in the second year I specialized in philosophy because I was attracted by complex thinking; I had read Lévi-Strauss early on - 'Triste Tropiques' when I was sixteen or seventeen; I was not so much attracted by anthropology, but by the man; someone who was obviously a great intellectual but had also gone to the furthest corners of Brazil to study, and write very warmly and humanely about the people; so it was the intellectual autobiography that attracted me to Lévi-Strauss rather than to anthropology as a discipline; I decided on philosophy as it was the best intellectual training, but at the same time started reading more serious books in anthropology; most of my friends in philosophy would restrict tehmselves to reading 'The Savage Mind', which I think is one of the most important books in philosophy of the twentieth century; while I also read 'The Elementary Structures of Kinship' which is a more technical book on anthropology; there are different École normale supérieure, one École normale supérieure where Latin was part of the examination; I chose another, École normale supérieure de Saint-Cloud, which is just outside Paris; for that, instead of Latin, there was a dissertation in geography, a subject I enjoyed very much; I was fortunate to be admitted at my first attempt; there I got a very good training in philosophy from great minds such as Jean-Toussaint Desanti, a philosopher of mathematics, Martial Gueroult, a great figure in the history of philosophy, a specialist on Spinoza & Descartes, a source of inspiration for Foucault; there I really became a militant; my friends were either in the Communist Party, and Maoists, but I was much more attracted by Trotskyism, and particularly by Trotsky as a man of action and an intellectual; I decided to become a member of the French section of the 4th International, called Ligue communiste révolutionnaire; I was a militant for three years when I was at the École normale supérieure; however I didn't much enjoy the militant life; most of the time we would endlessly discuss obscure points of doctrine or strategy which I felt was a bit ridiculous; at that time there were probably 4-6,000 members of the Trotskyist movement; we discussed how best to organize ourselves for the revolution, but even with the enthusiasm of the time it was obvious that the situation was not pre-revolutionary; when you enter the École normale supérieure and pass the examination, you become a Civil Servant and are paid as a teacher in training; I became a member of the teachers' trade union and many other things of this kinds, which took up a lot of time; after three years I felt that this was not the way for me to deal with the transformation of society; there were two dimensions at the time which I thought were important; I was very much interested in nature in general, but it was the beginning of the dawn of the idea that there were grave ecological problems and that politics had to take this into account; this was not at all the case with the extreme Left at the time; the other was gender politics, which was also considered a secondary problem; so after three years I left, discretely, but have never regretted this period; this was in 1973 when at the same time I took the decision to become an anthropologist; what made me decide was that Maurice Godelier, a former pupil at the École normale supérieure de Saint-Cloud, had just published 'Rationality and Irrationality in the Economy', an analytical criticism of neo-classical economics and a reading of Marx's 'Capital', but at the end there was an interesting development on the theme of pre-capitalist economies; he came back to the École normale supérieure to give a seminar on this book and over the next months he developed further the subject of pre-capitalist economies; I became quite interested and asked him if it was feasible to become an anthropologist; he said it was; I had become intellectually interested in the subject but had no idea how to do it; he told me I would have to do fieldwork; I passed the competitive examination to become a professor of philosophy and spent a year teaching the subject; however, before that I decided to go to Mexico in the summer to see whether fieldwork was possible; I had met my wife by this time - Anne-Christine Taylor - and we went together; prior to this, as I had no training in anthropology, at the same time that I was studying philosophy I went to the University of Nanterre and took a B.A. in ethnology; the year after that I went to the École pratique des hautes études (VIe section) where Lévi-Strauss was teaching as well as Godelier, in the Sixth Section which later became the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, for a year's training programme in anthropology; this had been created by Lévi-Strauss and we were very fortunate in our teachers - Godelier, Dumont was teaching kinship, Clastres was doing political anthropology; this was where I met Anne-Christine Taylor; she had been in Oxford for a while and was interested in doing anthropology in Central Asia; however, at that time it was not an area where one could freely do anthropology; we fell in love, and I tried to convince her to go with me to Latin America; I wanted to go there for various reasons; I spoke good Spanish through my father and grandfather; Africa appeared to me complex but without any real mystery, as for Asia in general there seemed such a complexity that I thought I would need infinite knowledge in order to grasp simple facts; in the first instance I chose Mexico; we went together to Southern Chiapas, where there were many anthropologists working at the time particularly in the Harvard Chiapas project; what I was interested in was a combination of political and ecological anthropology; I was interested in the way that the people of highland Chiapas, specifically the Tzeltal who were speaking a Mayan language, who had migrated down to the forest were adapting to a new environment; this was a tropical forest and the only Mayan speaking people living there were Lacandons who were quite different from the highland Maya and had complex relationships with the Tzeltal; I was interested in seeing how these people adapted to a new environment, both technically and ideologically; we spent a few months in a village in the midst of the Lacandon forest called Taniperla where I discovered the basic trade of being an ethnographer; it was not very satisfying because the Tzeltal had been pushed by the big landowners in the highlands so there was less and less land for them, and had been forced to migrate to the lowland as settlers; they were not really happy in this environment which was so different from the highlands, and they were trying to adapt precisely their institutions, the way they saw and organized space into social segments in the midst of this jungle chaos; they could not transpose this system so were very unhappy; their unhappiness affected me too and after a few months I decided it wasn't where I wanted to be; I had always been attracted by Amazonia but thought it was too petit bourgeois to go there because of the romantic image it had of naked Amazonians talking philosophy in hammocks wearing splendid feather adornments; but I had always been fascinated by that part of the world and my nickname at École normale supérieure was "les plumes" - feathers; despite my scruples I had discovered the tropical forest in Lacandonia and found it a wonderful place so decided to go to Amazonia; we came back to France at the start of the academic year of teaching philosophy; I went to see Lévi-Strauss as the authority on Amazonian Indians and asked him whether he would supervise my doctoral thesis; there were very few people qualified to supervise on that domain at the the time but it was for me like going to see Kant in Konigsberg; he was a major figure and one of the great heroes of our time; he received me in a large office and offered me a seat in a dilapidated leather armchair which I sank into; he sat on a wooden chair looking down at me while I spent the most difficult half-hour in my whole life trying to explain what I wanted to do; to my great surprise after hearing me he agreed to supervise my thesis and I was so elated; there were not many books on the subject of Amazonia at that time but both Stephen and Christine Hugh-Jones had written wonderful monographs on Colombia - 'The Palm and the Pleiades' and 'Under the Milk River' - which were very new in the panorama of anthropology of the Amazon; of books, they were almost the only ones as the others were just matter of fact reports lacking in insight; what fascinated me in Amazonia was that from the first narratives of the 16th century observers would insist on two things, one that these people had no institutions to speak of, and they were very close to nature, either in a positive or negative sense; in the positive sense, they were children of nature, naked philosophers, or they were prey to their instincts, therefore brutish, cannibals etc., not properly human; I had the impression there was a connection between the apparent lack of institution and the idea of nature folk, and that maybe their lack of apparent social institution was due to social life expanded much beyond the perimeter of humanity, and included most plants and animals; so I had this very general idea which attracted me to Amazonia; another aspect was of course what Clastres had insisted on, that these people were anarchists, rebels to authority, there was no fixed destiny for people, no hierarchy, so they were free to achieve what they wanted; their lives were not predicted by the place or social position of their birth; these were interesting things; we decided on the Achuar, a sub-group of the Jivaro; we had a friend who had come back from Ecuador doing fieldwork in the highlands, and talking with her she said the Jivaro where not as well-known as they appeared, which was bizarre because it was an ethnic group that everybody had heard of because of the shrunken heads; in fact we discovered when reading the literature on them that although there was a great monograph from the thirties by Rafael Karsten, the great Finnish anthropologist, in fact the most recent stuff was not very illuminating; there was still a sub-group of the tribe which spoke a dialect of the Jivaro that hadn't been studied, and they were the Achuar so we decided to go there to see what could be done; we went for an exploratory fieldwork and made sure that they existed as there were only scarce mentions of them in the literature; we got married first because we thought that with the missionaries it might be easier, and we went to Ecuador in 1976 as a sort of honeymoon which was to last three years

Second part

0:05:07 We decided to go to South America in a cargo boat which took three passengers; we started to learn the Jivaro language on the boat; only the main South American languages – quichua, aymara and guarani – were taught in France, but we had a friend, an Italian linguist, Maurizio Gnerre, who was the only professional linguist until now to have worked on Jivaro; it is an isolated language, spoken by approximately 100,000 people in the foothills of the Andes in the rain forest, and they occupy territory which is about the size of Portugal; so it is a very large ethnic group and probably the largest population in Amazonia speaking a single language; he gave us a small devise to teach yourself Jivaro with cassettes and a book by a missionary, and also help with pronunciation; we arrived in Ecuador, landing in Guayaquil, and went to the forest across the Andes to a small town called Puyo which was the end of the road; no one there knew how to get to the Achuar though some said they knew such people were living about 200km away; finally we got a lift from the Ecuadorian Army; they took us to a small army base in the forest by plane and there we were introduced to Quichua speaking people who were maintaining the base and being used as scouts and porters by the army; they were the neighbours to the north of the Achuar and used to trade with them; two of them said they would take us to the Achuar; we walked there with them and it took us about two days of our first real hard trek in the forest; in the evening we arrived at a group of houses where people seemed to be speaking a language similar to that we were learning; they had painted faces and long hair and the two guides left us saying they would never sleep in an Achuar village; there was a young man who knew some Spanish as he had worked for oil prospectors; he was our first contact as the little of the language we had learnt on the boat was not enough to communicate; that was the beginning of a long stay of almost two years continuously; after that we each got positions at the University of Quito where there was a department of anthropology which had been very recently created; no one at the time had any idea what Amazonian people were and had very little notion of kinship studies or things like that; we spent a further year in Ecuador alternating giving classes in Quito and going back to the field for shorter periods; it was a remarkable experience; I have written two books about it, one was my doctoral thesis on the relationship between the Achuar and their environment and the other is a more personal account of what it is to try to make some sense of a very foreign culture - 'The Spears of Twilight' - where I tried to recount precisely the progress that we made in getting to know these people

7:03:19 On the subject of boredom in fieldwork we did not have even the relief of the large rituals that Stephen Hugh-Jones described in his book; in fact, the only rituals they had were linked to warfare; the experience of fieldwork is long periods of boredom, much like village life; except for the few houses which were gathered round an airstrip which had been built for the Protestant missionaries, most of the houses were scattered as in the traditional habitat; you have to imagine arriving in a house with a polygynous family of maybe 30 people, and then you are completely isolated from any other house which may be one or two days walk or canoe away; it is a world where the humans are scarce; this is where I understood precisely one of the many reasons why there was such a close connection with non-humans; as soon as you go out of the house you won't see humans but are immersed in a sea of non-humans - plants and animals etc.; the boredom was precisely these long periods where nothing happened, where people would get excited in ritual discourse during visits when a minimum of information was exchanged; the boredom was also shattered by periods of feuding and warfare, when gossiping could lead to accusations of shamanic attack and escalate into small-scale war; at times I wondered whether warfare was not just a way to interrupt this boredom because there was sudden excitement and everybody woke up in a way; in contrast with an anthropologist working in a city or a large village, there were very few people for us to interact with; women go to the garden for the whole day where men are not welcome, neither are foreigners or even husbands; Anne Christine would go with the women; I had a shotgun and I was supposed to behave like a man but I was a terrible hunter; I would go out and one of the men would take me hunting with him, but I was very clumsy and most of the time I would scare off the animals; they would have much preferred that I hunted on my own; however, the knack of hunting is not shooting animals but finding them; that requires an expertise in ethology and a vast knowledge to connect clues as to where animals are which I could not have acquired; even among the Achuar, the best hunters were over 30-35 years old; a boy of 10 would be able to name about 300 birds, recognise them and imitate their sound, understand their behaviour and know what they feed on, but this incredible naturalist knowledge is not enough; it requires 20 more years experience, walking in the forest and being attentive to clues to become a good hunter, so I had no chance; that was a problem as there were no informants as everyone had gone off; we found the most productive period was early in the morning before dawn; the Achuar wake up around 4am, then gather round fires in the hut and discuss their dreams; they also talk about anything that is important at the time; this is the real moment for that sort of discussion and where important information can be acquired; at 6am everybody goes off and the long day begins

14:36:03 When I went to the Achuar it was with the idea of trying to understand how the society coped with its environment; at the time there were two main theories to deal with this; one was American materialism, cultural ecology, which was extremely deterministic and which held that in fact most institutions in small-scale societies of this type were the product of adapting to limiting factors in the environment; the main figure was Marvin Harris; some of his students had worked in Amazonia and a good deal of the literature in cultural ecology was either on New Guinea or Amazonia; I had my doubts about this for epistemological reasons because I felt it was a form of vulgar materialism and much too simple, but I wanted to do the same kind of analysis that the cultural materialists had done to see if it worked or not; the other was broadly speaking the symbolic or Lévi-Straussian paradigm, that nature was not something you adapted to in the sense of the cultural materialist, but it was a vast lexicon from which you extracted meaning in order to construct these meanings into symbolic constructs - classifications, myths etc.; I thought that what was left between the two was the interaction between humans and non-humans in this process, and this is what I went to study; however, when I began to understand the language, especially in the morning sessions when people would recount their dreams, they would say that they had been visited in the dream by a human-like entity, a howler monkey or manioc plant, and this entity would deliver a message complain; I remember vividly a case where a manioc plant appearing as a young woman was complaining that the mistress of the garden was trying to poison "her" as she had planted a species of plant used for poisoning fish too close; so non humans when we are not there lead the life of humans; we discovered also that the Achuar were constantly singing in their heads, either to plants and animals, spirits, or to humans who were not present; these songs were addressed from the heart to the heart of the addressee; the idea was to influence the behaviour of the entity addressed by these songs; every person had tens even hundreds of these songs which were adapted to all circumstances; in fact when they were doing their chores in the garden or hunting, they were constantly establishing a direct link through these songs to the non-humans with whom they were interacting; this is when I really became aware that the premises that I had gone with in my mental tool-box when I went to the field were unadapted; I was interested in studying precisely the adaptation of a culture to a natural environment and in fact nature and culture were not separate; they were meaningless concepts; there was a constant interaction between humans and non-humans, and non-humans were not perceived as nature but part of a wider network of social interactions; also as I did the vestigial but necessary analysis of the soils, plants, the density of planting, productivity of the soils, analysis of the plants in the forest and the gardens etc. which is the basis of my dissertation, 'In The Society of Nature'; however, I became aware also of the degree of manipulation of the plants out of the garden was enormous; each garden not only had a number of cultivated plants but also of plants that were transplanted from the forest; this manipulation of plants meant that the forest was in fact due to the cyclical nature of the swidden agriculture, regularly transformed by this and became progressively something like a macro garden; so there was not a raw nature which a raw society would adapt to, but a very complicated process of co-evolution between humans and non-humans in the very long term; when I came back to France and started writing my dissertation it became obvious that I could not frame that in the language either of materialism or of symbolism or Lévi-Straussian analysis; it was not the relationship of a culture to a specific nature; this is when I tried to figure out how best to rework the concepts I was using to describe this situation; to cut a long story short, when I got back - (I spent some time here in King's College) - I embarked on a monstrous project for my dissertation which I never completed as such because it would have taken me twenty years; I finally restricted it to what it is now; I decided not to teach philosophy in the lycée because I knew it would take too much of my time, and so we were living meagrely with a little teaching in anthropology; one day I went to the Maison des Sciences de l'Homme in Paris, an institution created by Fernand Braudel; at the time the head of the institution was a remarkable man called Clemens Heller, an Austrian historian, and he knew everyone; I would go and see him regularly to see if he had some subsidy for me; one of these days I arrived in his office and he told me Bernard Williams was here and that I should go and have lunch with him; we had a nice conversation and at the end he invited me to come to King's for a few months and Clemens Heller gave me the money for that so that in 1981 I finished writing my doctoral dissertation here, living in a small flat in King's Parade; that is when I discovered Cambridge; after that I was fortunate enough to get a teaching position at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and elected maître de conférences and I started a research seminar; this is where I really entered into a comparative framework trying to make sense of what I had observed in Amazonia and see how I could account for that with concepts that were not available on the intellectual market; research seminars are fabulous because when you finish your research dissertation you may be knowledgeable about the kinds of people you stayed with but you know nothing about anthropology; I really started learning my trade by teaching things I didn't know to people who knew less; this is when I embarked on reading systematically the ethnography of Amazonia and also on the ethnography of North America and the circumpolar regions including Siberia; this was because I saw that some of the features that I observed among the Achuar are present elsewhere in Amazonia and other parts of the world; so I came to call animism, this thing which I'd observed among the Achuar, the idea that most entities in the world have what I call an interiority, a subjectivity, a disposition to communicate, to lead internally the life of a human, but were differentiated by their bodies in the sense that their bodies give them access to specific parts of the world, disconnected parts, because the world of the fish is not the world of the bird, nor insect, nor human, because each of these classes of species have special bodily dispositions that open up for them something which is an expansion of this bodily disposition but which is restricted; this was the reverse of the way we see things usually and it is why it was initially so difficult to grasp it; we in Europe in the past centuries have seen humans having a distinctive interiority in contrast to any other beings in the world because we have a symbolic capacity, we have a language that expresses it, we have the cogito etc., but on the other hand we are a substance like any other which submits to the same laws of chemistry, physics etc. as the rest of the organic and non-organic beings in the world; so that was the reverse; I started toying with this idea that in fact all humans were able to see continuities and discontinuities between themselves and their environment and non-human environment, but did not necessarily see the continuities and discontinuities in the same place; we in the West would see them in the way that we have ended by calling them nature and society, or nature and culture, which is mainly predicated on this idea of the distinctivity of the interiority of humans, while among animist people the discontinuity was rather between physical worlds and the kind of perspective you could have on the physical world; since is was obviously not the case everywhere and I could not restrict myself with the idea of us and the rest, there were other formulas which were obviously very different from the animists, and especially Australia; when I began reading systematically on Australia I was struck by the fact that these people were also hunters, had a close relationship with the environment, but were completely different from the animist hunters in the countries that I had studied first and read about elsewhere, in the sense that there was no real interaction as from person to person between Australian aboriginals and the animals for instance; discoveries happen by chance; I remember reading a book by the linguist Carl Georg von Brandenstein; in a footnote, Brandenstein says a very important thing of which probably he was not even aware himself; it is a book on the name of totems in a number of aboriginal languages; he says that in some cases these names of totems are not names of species but name of qualities; so its not a 'kangaroo' but a 'bright one' which is used as an epithet to denote an animal; this was extremely interesting in the sense that it allowed me to sidestep the old idea of descent from an animal; you either have the Lévi-Straussian analysis of totemism as a universal classificatory device which uses discontinuities between natural species to conceptualize discontinuities between social species, but that is a universal device; or you have the Frazerian idea of descent from an animal ancestor, but in that case it was obvious that it was not an animal ancestor; it was a prototype which was defined by a quality and which subsumed a number of qualities that humans and non-humans of the totemic class would be sharing; so by contrast with the previous opposition what we had here was groups of humans and non-humans who shared qualities, physical and moral, subsumed under a name and issued from the same prototype; so by contrast with the other two ontological formulae, there was a coagulation of internal and bodily qualities; I called that totemism, obviously; I took Australia as the model of course, but it is present elsewhere, in particular in some places in North America but not from the place that the word ‘totem’ originates from which is the Ojibwe, but rather in the Southeast with people like the Creek and the Chickasaw; there was a missing piece where all that belongs or pertains to interiority or bodily functions or physicality is disconnected; this I thought I recognised because at that time I was reading Marcel Granet's book on Chinese thought, and re-reading a chapter of Michel Foucault 'The Order of Things - The Prose of the World' in which he analyses the devices used in Renaissance thought for connecting things; it was obvious that they were very close to the devices that Chinese thought was using to connect things; so I started in this direction and the fourth ontological formula (besides animism, naturalism and totemism) is one where everything in the world at the infraindividual level is made of fragments that are disconnected and in order for such a world to become liveable, interpretable, cognizable, these disparate elements need to be connected; they are connected by correspondences; correspondences are systematically organised by analogical reasoning; such reasoning is universal but is very much pre-eminent in these ways of detecting continuities and discontinuities between things in the world; this is why I call that analogism; it is something that was present in ancient Greece and up to the Renaissance in Europe, but also in the Far East; I particularly analysed it in the case of cultures I have a stronger purchase which are central Mexico and the Andes where it is very obvious that we have analogous systems; so this is four ways of detecting precisely continuities and discontinuities between elements of the world which are models; I do not pretend that they describe specifically a situation, but they are models in the sense that they provide a general understanding of the connections between different elements which we tend to dissociate - societies, religion, the relationship to the spirits, forms of subjectivity etc. - in a rather integrated manner; all this started precisely from my discontent with the intellectual tools I had brought with me to the field and which led me to try to reconfigure these tools in order to be more faithful to the kind of situations which anthropologists find when they do fieldwork

39:28:21 Coming back from the field was extremely difficult; it was almost an ordeal; when you come back you find that many dimensions of the world you come back to are pointless; what I found most difficult was the mediation of goods, when I was struck by the accuracy of Marx' analysis of petty commodity fetishism, the fact that social relations are mediated by objects; I became detached from objects at the time and I very rarely buy things when I travel now as I am oppressed by objects; this became obsessive when I came back; I had the constant impression of objects mediating between me and other people; this comes out of the fact that we had lived for two years with the Achuar with very few things, and had lived very happily; of course there were things that I missed and it is when you are in the field that you really appreciate and know what you look for in your own culture and what is important to you; some pieces of music, and landscapes that I was used to from my youth in Southern France, these I missed; but not the objects; this meant there was a widening of distance and that we lead a double life in a way; we live a social life because I am, what is called in France, a Mandarin; I am at the top of the pecking order in the French university system, but at the same time I always have the impression that I have a dissociative personality and I observe myself as an actor in the theatre of life; this was the case before but it was considerably augmented as a feeling after I came back

43:21:12 Going with a wife or partner to the field will either make or break a relationship; in my case it worked wonderfully because we were both partners and lovers; it worked well also because of the division of labour in fieldwork; it is paradoxical that the Achuar live in large long-houses with no internal separation so men and women appear to be mixed but they are not at all mixed; so there is a strong invisible barrier between men and women and I was confined to the male part of social life and Anne Christine was at ease with the women; so we really led two different lives during most of the day; we have never in fact collaborated; I think we have written one article together because from the beginning we wanted to be independent as producers of science from one another; we were never in the same institutions in France though we both worked in Paris; we constantly discussed, both in the field and afterwards, our hypotheses but never working as a couple producing things together; I think it is a good balance in that sense; in the field I would sometimes be alone as there were some places where my best Achuar friends would tell me that it would not have been appropriate for Anne Christine to go, places in the territory where there was a war going on so I would go alone, but most of the time we were together; it was an ideal situation as if you are a man alone it is very difficult; the world of women is absolutely off limits, and the Achuar are quite jealous so there may be suspicion that you are trying to seduce women; if you are a woman alone it is not good either because you are treated as a quasi man by the women and not really as a man by the men; so working as a couple, both for personal reasons and scientific reasons was the best choice

47:13:17 Finally after all these years I think I can make a comeback in politics in a way, not as the kind of militant that I was initially, but trying to reconcile the deep concern that I have for nature, for the fate of ecology, the problem of global warming and species extinction; I think my experience of fieldwork and seeing people deal politically in fact with non-humans in a very specific way has helped me to understand and perhaps foster a new way to deal with what is called both political anthropology, the study of social organization, and more generally speaking the political programme, than if I had not had this experience; this is what I would like to devote my thoughts to once I have finished the book I am writing on the anthropology of images

0:05:07 Born in Paris in 1949; my father was a historian and my paternal family came from the Central Pyrenees; my grandfather was a medical doctor, his father was a journalist, and my great aunt was a novelist; on the maternal side, my mother was the daughter of an army officer who died young, and he came from a military family; I was brought up in a family of the classical French Catholic bourgeoisie; we lived near the Tuileries in Paris; my father saw himself as Catholic but was not really practising as such; my mother probably had a deeper faith, and I was brought up a Roman Catholic, became agnostic, and was an atheist by about ten or twelve; this was not a problem for my family who were not trying to bring me up in any particular faith; in contrast with other anthropologists who tend to belong to minority faiths, I was raised in a straight-forward way; I went to the Lycée Condorcet which was one of the elite schools in Paris

3:22:21 My father was a brilliant man, a good conversationalist and very charming; he specialized in the history of South America and Spain although he had begun by working on St John of the Cross during a time when he was attracted towards mysticism; he always left me to do what I wanted; I had a very happy childhood; I lived surrounded by books any of which I could read, and I read a large part of the family library early on; there were many pictures and my paternal grandmother was a painter and so was her father; my parents loved music so I was introduced to it very young; my mother was a social worker, a working woman, and I was mostly left to do what I wanted; I have an older sister, thirteen years older, who was in fact the person I was closest to because my parents were not at home most of the day; I still am very fond of her; so I had a very agreeable childhood in the centre of Paris which I really loved; very early on I was allowed go wherever I wanted so I explored the city; I think my earliest memory is of the Pyrenees where we would go in the summer, although the family house had been sold during the Great Depression; we would go with my grandparents, and my earliest memory was the commotion when my parents thought that I was lost at a fair in the village of Seix in Ariège; it is a beautiful place from where you can walk up the mountains and over to Spain, which I did several times later with my parents and grandparents; my grandfather was an ophthalmologist, very well educated and erudite, knew Latin and Greek, and helped me with my essays; he also knew a number of modern languages which he never spoke; he was very proud and did not want to be accused of speaking like a hotel porter; he was also a very good naturalist, so when we walked together he would tell me the names of flowers; at night he would tell me the names of the constellations and their connection to Greek mythology; thus I was immersed very early on in the written word, the classical world, and a liking for the natural world and walking, and the connections between them; I think I must have been about five when I remember my parents fear that I was lost; I think I was watching some sort of show; among hobbies, I liked making scale models but also model theatres in shoe boxes, but my main pursuit was reading, and also drawing and painting; however, from an early stage I remember feeling that I was an observer rather than being absolutely involved in what was going on; this is one of my earliest impressions of the relationship I had with the world; it was amplified by an early ethnographic experience; when I went to the Lycée Condorcet at about ten, I was not a very good pupil to begin with; I had good marks in French and Latin, but not so good for the rest; my English teacher told my parents that I wasn't doing too well so they decided to send me to an English boarding school; the end of the French term was mid-June, a month earlier than in England, so I would go from the beginning of May, by agreement with the Lycée, to the end of July, to a rather decrepit Public School in Gloucestershire called Leckhampton Court; it was a remarkable experience; the school was in an old manor house, set up by the Headmaster, and it disappeared when he retired; I went to see what had happened to it some years ago and it is now a retirement home; in this school I discovered it was the absolute opposite to the French system; the Lycée, though I was not a boarder, was very military in its organization; it was devised by Napoleon as an elite form of schooling for the French nation, based on the Jesuit system, whereby we were extremely controlled and there was no leeway for personal initiative; what I found quite extraordinary in the English system was that we were living in an area of this manor house and never saw any adults; discipline was enforced by the prefects which was extraordinary for me; it was not far from Cheltenham in very nice surroundings, so I enjoyed that; I was never bullied; I have never been keen on team sports which is another aspect of personal distance; I did some fencing, and thanks to my sister who was a fanatic horse rider, I learnt to ride early on; these I enjoyed; I played football for a while because I had to but didn't enjoy it; in France one generally had to go quite far to sports' grounds; some keen friends did, but I did not; this first experience of another system was informative, not yet to become an anthropologist, but to enjoy the diversity of the world; I began to be a better pupil later on when there was more liberty of freedom in how we learnt, and that was in the last three years at the Lycée; my parents allowed me to travel, and my first experience was to go to Canada where my father had a friend who ran a mink farm, north of Quebec; I spent several weeks there working; I must have been about seventeen at the time; I then took a boat going from Quebec to Chicago via the Great Lakes, so went to the United States for the first time; it was the time of the riots in the ghettos of Newark and Chicago, and I was struck by the violence of this society; the National Guard, patrolling with guns and letting loose the dogs, which was something I had never seen in France; of course, France had done so in Algeria but I had been too young to know that; in fact I found out what had been going on in Algeria while I was at school in England; there was a television room for the pupils and we were watching the news; I was too young to read the newspaper and these were things that were not discussed at home; we also had no television at home; the year after the Canada visit I went to Turkey, Iran, Northern Syria, all on my own; looking back it is incredible but all our generation did these things; we could travel very far with little money and we thought the world was open for us; there was probably some neo-colonial covert ideology in that in the sense that nothing could happen to us; in my family among the books was a magazine series 'Le Tour du Monde', the equivalent to 'National Geographic' at the end of the nineteenth century; there were items by geographers and proto-anthropologists of travels in different parts of the world, illustrated with etchings in black and white; I was fortunate enough to have early editions of Jules Verne illustrated by the same persons, so there was a porosity for me between novels and the accounts of travel in faraway places; when I started travelling in the Near East it was as though some of these illustrations had come alive; I remember waking in a bus in Central Anatolia and seeing the minarets in a village and a caravan of camels, and I really had the impression that I had entered into one of those etchings; so very early on I had enjoyed spectacle of the world and its diversity; intellectually at that time I loved the French language and writing, and had got good marks in that domain since I was very young; now in 1967-8 I became politically conscious; with many of my friends, we were curious of everything - of the counter-culture in the United States, of new ideas, and at the time the main place where our political conscience was forged was the 'Committees Vietnam'; it was at the level of the Lycée, where we would protest against the Vietnam war and organize demonstrations; this is where we became conscious of the iniquity of imperialism and class although I had never suffered from any oppression myself; until the mid-seventies the Lycée was the preserve of the middle-class, so a minority of people would study for the Baccalaureat and go to university; when faced with the choice of studies at university I decided with some schoolmates to prepare for an elite school the École normale supérieure; it may appear bizarre from the fact that I was drawn towards leftist politics, but at the same time we were conscious of the complexity of the social and political situation which required a keen analytical mind; that we needed to exercise our brains as criticism of the situation required intelligence and knowledge; at the time some thought we should embed ourselves with the workers in order to preach revolution; we thought that, rather that to do so, we ought to acquire the intellectual instruments of criticism required to change the system; after the Baccalaureate I entered the classe préparatoire at the Lycée to prepare for the École normale supérieure; usually you prepare over two years, it is a highly competitive system where you are accepted on the basis of your marks at the Baccalaureate; between the subsequent first and second year, only about 30% of the class remain, and at the end of the second year there is a competitive examination for the entrance to École normale supérieure; about one in forty get accepted; in the second year I specialized in philosophy because I was attracted by complex thinking; I had read Lévi-Strauss early on - 'Triste Tropiques' when I was sixteen or seventeen; I was not so much attracted by anthropology, but by the man; someone who was obviously a great intellectual but had also gone to the furthest corners of Brazil to study, and write very warmly and humanely about the people; so it was the intellectual autobiography that attracted me to Lévi-Strauss rather than to anthropology as a discipline; I decided on philosophy as it was the best intellectual training, but at the same time started reading more serious books in anthropology; most of my friends in philosophy would restrict tehmselves to reading 'The Savage Mind', which I think is one of the most important books in philosophy of the twentieth century; while I also read 'The Elementary Structures of Kinship' which is a more technical book on anthropology; there are different École normale supérieure, one École normale supérieure where Latin was part of the examination; I chose another, École normale supérieure de Saint-Cloud, which is just outside Paris; for that, instead of Latin, there was a dissertation in geography, a subject I enjoyed very much; I was fortunate to be admitted at my first attempt; there I got a very good training in philosophy from great minds such as Jean-Toussaint Desanti, a philosopher of mathematics, Martial Gueroult, a great figure in the history of philosophy, a specialist on Spinoza & Descartes, a source of inspiration for Foucault; there I really became a militant; my friends were either in the Communist Party, and Maoists, but I was much more attracted by Trotskyism, and particularly by Trotsky as a man of action and an intellectual; I decided to become a member of the French section of the 4th International, called Ligue communiste révolutionnaire; I was a militant for three years when I was at the École normale supérieure; however I didn't much enjoy the militant life; most of the time we would endlessly discuss obscure points of doctrine or strategy which I felt was a bit ridiculous; at that time there were probably 4-6,000 members of the Trotskyist movement; we discussed how best to organize ourselves for the revolution, but even with the enthusiasm of the time it was obvious that the situation was not pre-revolutionary; when you enter the École normale supérieure and pass the examination, you become a Civil Servant and are paid as a teacher in training; I became a member of the teachers' trade union and many other things of this kinds, which took up a lot of time; after three years I felt that this was not the way for me to deal with the transformation of society; there were two dimensions at the time which I thought were important; I was very much interested in nature in general, but it was the beginning of the dawn of the idea that there were grave ecological problems and that politics had to take this into account; this was not at all the case with the extreme Left at the time; the other was gender politics, which was also considered a secondary problem; so after three years I left, discretely, but have never regretted this period; this was in 1973 when at the same time I took the decision to become an anthropologist; what made me decide was that Maurice Godelier, a former pupil at the École normale supérieure de Saint-Cloud, had just published 'Rationality and Irrationality in the Economy', an analytical criticism of neo-classical economics and a reading of Marx's 'Capital', but at the end there was an interesting development on the theme of pre-capitalist economies; he came back to the École normale supérieure to give a seminar on this book and over the next months he developed further the subject of pre-capitalist economies; I became quite interested and asked him if it was feasible to become an anthropologist; he said it was; I had become intellectually interested in the subject but had no idea how to do it; he told me I would have to do fieldwork; I passed the competitive examination to become a professor of philosophy and spent a year teaching the subject; however, before that I decided to go to Mexico in the summer to see whether fieldwork was possible; I had met my wife by this time - Anne-Christine Taylor - and we went together; prior to this, as I had no training in anthropology, at the same time that I was studying philosophy I went to the University of Nanterre and took a B.A. in ethnology; the year after that I went to the École pratique des hautes études (VIe section) where Lévi-Strauss was teaching as well as Godelier, in the Sixth Section which later became the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, for a year's training programme in anthropology; this had been created by Lévi-Strauss and we were very fortunate in our teachers - Godelier, Dumont was teaching kinship, Clastres was doing political anthropology; this was where I met Anne-Christine Taylor; she had been in Oxford for a while and was interested in doing anthropology in Central Asia; however, at that time it was not an area where one could freely do anthropology; we fell in love, and I tried to convince her to go with me to Latin America; I wanted to go there for various reasons; I spoke good Spanish through my father and grandfather; Africa appeared to me complex but without any real mystery, as for Asia in general there seemed such a complexity that I thought I would need infinite knowledge in order to grasp simple facts; in the first instance I chose Mexico; we went together to Southern Chiapas, where there were many anthropologists working at the time particularly in the Harvard Chiapas project; what I was interested in was a combination of political and ecological anthropology; I was interested in the way that the people of highland Chiapas, specifically the Tzeltal who were speaking a Mayan language, who had migrated down to the forest were adapting to a new environment; this was a tropical forest and the only Mayan speaking people living there were Lacandons who were quite different from the highland Maya and had complex relationships with the Tzeltal; I was interested in seeing how these people adapted to a new environment, both technically and ideologically; we spent a few months in a village in the midst of the Lacandon forest called Taniperla where I discovered the basic trade of being an ethnographer; it was not very satisfying because the Tzeltal had been pushed by the big landowners in the highlands so there was less and less land for them, and had been forced to migrate to the lowland as settlers; they were not really happy in this environment which was so different from the highlands, and they were trying to adapt precisely their institutions, the way they saw and organized space into social segments in the midst of this jungle chaos; they could not transpose this system so were very unhappy; their unhappiness affected me too and after a few months I decided it wasn't where I wanted to be; I had always been attracted by Amazonia but thought it was too petit bourgeois to go there because of the romantic image it had of naked Amazonians talking philosophy in hammocks wearing splendid feather adornments; but I had always been fascinated by that part of the world and my nickname at École normale supérieure was "les plumes" - feathers; despite my scruples I had discovered the tropical forest in Lacandonia and found it a wonderful place so decided to go to Amazonia; we came back to France at the start of the academic year of teaching philosophy; I went to see Lévi-Strauss as the authority on Amazonian Indians and asked him whether he would supervise my doctoral thesis; there were very few people qualified to supervise on that domain at the the time but it was for me like going to see Kant in Konigsberg; he was a major figure and one of the great heroes of our time; he received me in a large office and offered me a seat in a dilapidated leather armchair which I sank into; he sat on a wooden chair looking down at me while I spent the most difficult half-hour in my whole life trying to explain what I wanted to do; to my great surprise after hearing me he agreed to supervise my thesis and I was so elated; there were not many books on the subject of Amazonia at that time but both Stephen and Christine Hugh-Jones had written wonderful monographs on Colombia - 'The Palm and the Pleiades' and 'Under the Milk River' - which were very new in the panorama of anthropology of the Amazon; of books, they were almost the only ones as the others were just matter of fact reports lacking in insight; what fascinated me in Amazonia was that from the first narratives of the 16th century observers would insist on two things, one that these people had no institutions to speak of, and they were very close to nature, either in a positive or negative sense; in the positive sense, they were children of nature, naked philosophers, or they were prey to their instincts, therefore brutish, cannibals etc., not properly human; I had the impression there was a connection between the apparent lack of institution and the idea of nature folk, and that maybe their lack of apparent social institution was due to social life expanded much beyond the perimeter of humanity, and included most plants and animals; so I had this very general idea which attracted me to Amazonia; another aspect was of course what Clastres had insisted on, that these people were anarchists, rebels to authority, there was no fixed destiny for people, no hierarchy, so they were free to achieve what they wanted; their lives were not predicted by the place or social position of their birth; these were interesting things; we decided on the Achuar, a sub-group of the Jivaro; we had a friend who had come back from Ecuador doing fieldwork in the highlands, and talking with her she said the Jivaro where not as well-known as they appeared, which was bizarre because it was an ethnic group that everybody had heard of because of the shrunken heads; in fact we discovered when reading the literature on them that although there was a great monograph from the thirties by Rafael Karsten, the great Finnish anthropologist, in fact the most recent stuff was not very illuminating; there was still a sub-group of the tribe which spoke a dialect of the Jivaro that hadn't been studied, and they were the Achuar so we decided to go there to see what could be done; we went for an exploratory fieldwork and made sure that they existed as there were only scarce mentions of them in the literature; we got married first because we thought that with the missionaries it might be easier, and we went to Ecuador in 1976 as a sort of honeymoon which was to last three years

Second part

0:05:07 We decided to go to South America in a cargo boat which took three passengers; we started to learn the Jivaro language on the boat; only the main South American languages – quichua, aymara and guarani – were taught in France, but we had a friend, an Italian linguist, Maurizio Gnerre, who was the only professional linguist until now to have worked on Jivaro; it is an isolated language, spoken by approximately 100,000 people in the foothills of the Andes in the rain forest, and they occupy territory which is about the size of Portugal; so it is a very large ethnic group and probably the largest population in Amazonia speaking a single language; he gave us a small devise to teach yourself Jivaro with cassettes and a book by a missionary, and also help with pronunciation; we arrived in Ecuador, landing in Guayaquil, and went to the forest across the Andes to a small town called Puyo which was the end of the road; no one there knew how to get to the Achuar though some said they knew such people were living about 200km away; finally we got a lift from the Ecuadorian Army; they took us to a small army base in the forest by plane and there we were introduced to Quichua speaking people who were maintaining the base and being used as scouts and porters by the army; they were the neighbours to the north of the Achuar and used to trade with them; two of them said they would take us to the Achuar; we walked there with them and it took us about two days of our first real hard trek in the forest; in the evening we arrived at a group of houses where people seemed to be speaking a language similar to that we were learning; they had painted faces and long hair and the two guides left us saying they would never sleep in an Achuar village; there was a young man who knew some Spanish as he had worked for oil prospectors; he was our first contact as the little of the language we had learnt on the boat was not enough to communicate; that was the beginning of a long stay of almost two years continuously; after that we each got positions at the University of Quito where there was a department of anthropology which had been very recently created; no one at the time had any idea what Amazonian people were and had very little notion of kinship studies or things like that; we spent a further year in Ecuador alternating giving classes in Quito and going back to the field for shorter periods; it was a remarkable experience; I have written two books about it, one was my doctoral thesis on the relationship between the Achuar and their environment and the other is a more personal account of what it is to try to make some sense of a very foreign culture - 'The Spears of Twilight' - where I tried to recount precisely the progress that we made in getting to know these people

7:03:19 On the subject of boredom in fieldwork we did not have even the relief of the large rituals that Stephen Hugh-Jones described in his book; in fact, the only rituals they had were linked to warfare; the experience of fieldwork is long periods of boredom, much like village life; except for the few houses which were gathered round an airstrip which had been built for the Protestant missionaries, most of the houses were scattered as in the traditional habitat; you have to imagine arriving in a house with a polygynous family of maybe 30 people, and then you are completely isolated from any other house which may be one or two days walk or canoe away; it is a world where the humans are scarce; this is where I understood precisely one of the many reasons why there was such a close connection with non-humans; as soon as you go out of the house you won't see humans but are immersed in a sea of non-humans - plants and animals etc.; the boredom was precisely these long periods where nothing happened, where people would get excited in ritual discourse during visits when a minimum of information was exchanged; the boredom was also shattered by periods of feuding and warfare, when gossiping could lead to accusations of shamanic attack and escalate into small-scale war; at times I wondered whether warfare was not just a way to interrupt this boredom because there was sudden excitement and everybody woke up in a way; in contrast with an anthropologist working in a city or a large village, there were very few people for us to interact with; women go to the garden for the whole day where men are not welcome, neither are foreigners or even husbands; Anne Christine would go with the women; I had a shotgun and I was supposed to behave like a man but I was a terrible hunter; I would go out and one of the men would take me hunting with him, but I was very clumsy and most of the time I would scare off the animals; they would have much preferred that I hunted on my own; however, the knack of hunting is not shooting animals but finding them; that requires an expertise in ethology and a vast knowledge to connect clues as to where animals are which I could not have acquired; even among the Achuar, the best hunters were over 30-35 years old; a boy of 10 would be able to name about 300 birds, recognise them and imitate their sound, understand their behaviour and know what they feed on, but this incredible naturalist knowledge is not enough; it requires 20 more years experience, walking in the forest and being attentive to clues to become a good hunter, so I had no chance; that was a problem as there were no informants as everyone had gone off; we found the most productive period was early in the morning before dawn; the Achuar wake up around 4am, then gather round fires in the hut and discuss their dreams; they also talk about anything that is important at the time; this is the real moment for that sort of discussion and where important information can be acquired; at 6am everybody goes off and the long day begins