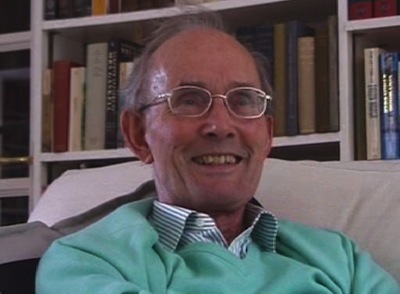

Brian Harrison

Duration: 2 hours 57 mins

Share this media item:

Embed this media item:

Embed this media item:

About this item

| Description: | An interview of the historian, Sir Brian Harrison, made by Alan Macfarlane on 22nd June 2012 and edited by Sarah Harrison. |

|---|

| Created: | 2013-02-05 13:12 |

|---|---|

| Collection: | Film Interviews with Leading Thinkers |

| Publisher: | University of Cambridge |

| Copyright: | Prof Alan Macfarlane |

| Language: | eng (English) |

| Keywords: | history; Oxford University; temperance; National Biography; Brian Harrison; |

Transcript

Transcript:

Brian Harrison interviewed by Alan Macfarlane 22nd June 2012

0:05:07 Born in 1937 in Belsize Park, London; my father was a buyer in the toy department in Peter Robinson, which was then an important London store; my mother had been a junior in the hat department before going to McCracken & Bowen, hat makers in Marylebone; when she left Peter Robinson they organized a whip-round for a leaving present, and my father contributed; they bought her a silver visiting card container, which I still have; she went round to all those who had subscribed and thanked them; I am here now because this was how she met my father; my father still worked at Peter Robinson after they married but my mother was a housewife, as was normal at that time; she had a terrible time with me because I cried all the time; at one point she just ran away; my father found her going down in the lift at Belsize Park; I was one or two at the time and my father was appalled; her mother had died in the 'flu epidemic at the end of the First World War and her father had died, allegedly of a broken heart, three years after when she was four or five; she never really had a mother and always felt the need for one; a mother would have advised her how to deal with a crying child; very fortunately there was a charming woman called Mrs Blackstock who lived in a nearby flat in Glenloch Court and took my mother in hand and told her how to cope; my father was a very interesting man in many ways; he had all sorts of theories, and one of them was that you don't do any washing-up at the weekend; my mother found herself on Monday mornings with a huge pile, and Mrs Blackstock helped her, giving advice on how to deal with her husband; not surprisingly, my father didn't like Mrs Blackstock's influence; this may have had an important effect on me as my mother told me that Mrs Blackstock's son, Ewart, had dropped me on my head when I was a baby; my father was furious and never let Ewart hold me again; the very first school report that I had said I positively revelled in work, and that has been so since; I enjoy working and am a workaholic; I have been very fortunate in being in a profession where work cumulates in some sense, and means that my life has a harmony about it which most people don't have; there is no distinction between weekends and week days, holidays or work days; it had already begun when I went to prep school, as my school reports testify.

5:55:22 I went to a good school because my mother was socially ambitious; she viewed education as a way of moving up, or at least not moving down; my father was very much in favour of a good education, but for the right reasons and felt that people should realize their full potential; between them they reached the same conclusion that I should be sent to Alcuin House School which was a little prep school with probably not more than a hundred pupils; I got a very good education there; Miss Dalgleish was very encouraging; I was a nervous child and had a term when I was completely off school altogether; I was then about six or seven; for some reason I was frightened of going, though I don't remember being bullied; they kept me at home and Miss Dalgleish wrote a letter saying they were looking forward to seeing me next term; I did go back and it was all right after that; my parents were very good in trying to understand what the problems were, but I got very good school reports; the school had a really outrageous system by present standards; when you came top of the class you were given what was called a ‘list’ which was a list of all the pupils in rank order of performance; I kept on getting all the lists; at the end of term you would walk up to receive your list from the headmaster - T. D’Arcy Yeo was his name - and I walked off with all the lists; my parents therefore knew I was bright and did everything they could to encourage it; that school got me to Merchant Taylors' School in Northwood; my performance in Latin peaked at Alcuin House at thirteen; I was never taught it as well at Merchant Taylors’; we were all being prepared for Common Entrance which was the way you got into a public school; you didn't do 11+, you took it at thirteen and you either got in or not; I got an Exhibition, not a Scholarship, to Merchant Taylors’, which was something like £40 a year; my mother had a brother who was quite affluent and he helped out a bit

9:13:12 Going back to my mother's history - the Savill family were the Shaw Savill shipping line, quite a big operation in the Edwardian period; they were also brewers in North-East London and Savills, the land agents; my grandfather, Martin Savill, was regarded as the "poor" branch of the family; when my grandfather died soon after my grandmother, possibly through drink rather than a broken heart, the wealthier sections of the family took an interest and really wanted to help; there were seven siblings, two had already gone to Australia and Canada, and both founded quite big clans there; the other five stayed in England; Meredith was seriously crippled and became the centre of the family; he was a charming person, very much loved by everybody; Margot and my mother couldn't earn very much, neither could Tom who was too young to work, and there was Geoffrey who was apprenticed to CAV, an engineering firm in Acton; he was head of the family, and despite pressure from the rich members of the family to take over, they wanted to remain independent and were terrified of being separated from one another; my mother always said that she had a very happy childhood, brought up by her siblings, but never had a mother to guide her through the business of being a woman; I am always astonished that I ever appeared on the scene; as a young woman she did not know anything about sex, like a lot of women at that time; somehow I was conceived, but she remained very innocent in all sorts of ways; I think she was sort of in love with my father, but I don't really know; but throughout her life she gave misleading signals to men so they thought she was fond of them when really she was just trying to be nice; it lead to all sorts of misunderstanding, particularly when she separated from my father; she always said that the difference in their ages didn't matter, my father was about twenty years older, but that the cause of the dispute was that he was unreliable about money; when I was a teenager people used to knock at the door asking for their bills to be paid; my mother was quite terrified by that because her brothers had always paid their bills; they separated when I came back from the army after National Service so it did not have any traumatic effect on me, but I remember lying in bed upstairs and hearing them arguing when I was a teenager; my mother used to burst into tears, my father would get rather loud, and my mother would tell him not to shout; it's curious how children react; people would now say that it was lethal, but it wasn't at all; it was like a thunderstorm and I rather liked them, it didn't worry me but was just something that happened

14:51:17 When my mother was turning against my father she took me into consultation; it was a fatal thing to do, but I was rather flattered, and she talked to me about all sorts of confidential things; she told me that she was thinking of taking over the front bedroom, hitherto shared; I usually agreed with her but I did think it wrong to push my father into the back room; these consultations had the effect of putting me against my father which was a pity; I can't say much about him; he was a clever man, an accountant by training, and self-made; I don't really know anything about his parents; my mother used to, under duress, entertain her mother-in-law at home at Christmas, but didn't like her at all; I never went up to Yorkshire where they lived; my father came from Hull, but his father allegedly ran off to Canada; I don't go any further back on that side but can go much further on my mother's side; my father was a clever man, and he thought for himself; in the Second World War he resigned or was sacked from Peter Robinson and started up on his own as a toy manufacturer in Percy Street, just off Tottenham Court Road; I used to go there sometimes; they made a great fuss of me because his employees were refugees; Miss Rosenzweig was the woman who ran the workshop; she was a Jewish refugee from Czechoslovakia; very paradoxically as my father was anti-Jewish, even though he was making money out of them; he used to refer to Jews as "shonks" which is an insulting word; the frightful things that happened in the war didn't seem to affect that at all; this attitude carried over into my mother; by the 1950s it was not acceptable to say such things and I had to advise my mother not to; my father was a curious mixture; he tended to vote Liberal, but out of perverseness because nobody else did; he was disorganized; his study was a terrible mess; my mother used to tidy him up but without any success; behind all my card indexes lies a mother who said I must not be like my father; I used to love going to my Aunt Bim who lived in Chelsfield, Kent; I used to go with my Aunt Margot and she made gooseberry pie, which I loved and still do; after the pie I would clear out one of her cupboards which I loved, and that is what historians do, they tidy up things, make sense of chaos, they find buried treasure, and all that goes right the way back for me; the War also had a profound effect because when I was three we moved to Stanmore, to a half-finished suburban estate where building had stopped because of the War; there were lots of spaces between houses and they were full of rusting railway trucks left over from the builders; we had the most wonderful time on the building plots, there were trees and fields round about, and Bentley Priory where Bomber Command was, was nearby; it was a lovely place to spend one's childhood; it was highly suburban, and I've been suburban all my life, which is an ideal combination of privacy and companionship; it's an ideal mixture and I've never had any of this snobbish objection to being suburban; my mother used occasionally to use the word pejoratively but I never have; I had a gang of friends there and we roamed around on our own unsupervised, as was common among children then, and in those days you could play in the street, with cars rarely seen.

21:50:00 I had lots of hobbies - cigarette packet covers which we would pick up out of the gutter; I was a great collector then and still am; I had a stamp collection; I had a room of my own and never wanted for anything, and if you haven't seen a banana you are not worried about not having one; I remember my father drawing a banana in about 1947, and eating one about a year or so after that and wishing it would never end; I remember where I was sitting when I ate it; the War had the effect of maximizing the companionship side of neighbourhood because the men were mostly away and the women got together; my mother and I had jaundice when I was nine and the neighbours weighed in and brought food; there was a great deal of fellow feeling, but that nourished the anti-Jewish feeling because the thing that really terrified everybody on the estate was whether the place would be taken over by Jews as they were moving out across North-West London towards us; they were doing well, had come out of the East End and got as far as Golders Green and Hendon, and were likely to move further out; that was thought to be appalling as it would drag the estate down; I remember my parents complaining about somebody shouting to her husband in the garden from an upstairs window; you just didn't do that sort of thing; it was a class thing partly, they were frightened of the estate going downhill and losing its cachet and its house-value; it's not so much social aspiration that drives them but the fear of social decline; my mother's family were at risk of going down, and her class-consciousness and desire for my education, aimed to stop that happening; they all clutched on to the one brother (Geoffrey) who had money and bailed them out; he never married, and to put it crudely, he allowed himself to be plundered; he was a very good-hearted man; my father was dragging my mother down; he was made aware that she had married beneath her; she used to refer to people as being ‘provincial’ which meant that they came from north of Watford, and my father was decidedly provincial coming from Hull; he used to get awfully cross when she used that expression; my father was a very kind man and he subsidized his brother Eddie in getting through university; my uncle eventually became a university registrar and did quite well; but it is typical of my father that when I went to Malta on National Service he used to send parcels of chocolate, which I was extremely fond of, but they had gone white; he hadn't noticed that in the shop that he kept by that time, they had passed their prime and were largely uneatable, even by me; he had an accountancy business and both it and the toy business drained down to nothing, so he was sinking and that is why the bills were not paid; my mother was determined he should not sink any further so she went out to work in a part-time job which was something middle-class women didn't do in those days; it was brave of her, and was in fact the making of her because she discovered that she was a very good manager; in the early 1950s her brother Geoffrey set them both up in a shop in North Kensington, a working-class area with black immigrants beginning to come in; they ran this sub-post office, corner shop, very well - so much so, that they got a second shop in the Harrow Road; the way things were going, my mother continued to run the old shop and my father ran the Harrow Road shop; when I came back from the army at twenty-one, I found that the marriage was breaking up, so it was not a happy home-coming; I volunteered to open the Harrow Road shop on Sundays to test the market, as my father had ceased opening it then; I had worked behind the counter as a teenager for them in the other shop, and rather enjoyed doing so, and I am a natural entrepreneur probably as a result of that; I only did one Sunday and thought my father really ought to know what his stock was like and why people were not buying it; his response was that there was nothing wrong with the stock; you couldn't tell my father anything really, he was never wrong, but I did my best. At that time I needed to get some money together as I was coming up to Oxford; I went by bicycle to Kilburn because my mother insisted that I should get a job, to an employment agency; I filled in a form and was rather shocked to see how little I could offer because the only thing I could do was to type; that was one of the reasons why I made myself a proficient touch-typist thereafter, because I thought that at the very least I would be able to do that; in fact, no job was offered me, and my father knew one of the buyers in Selfridges with whom he spoke, and I got a job in the gramophone department through no merit of my own but just through my father putting in a word for me; I was extremely good at it; we were paid on commission so it was financially rather important to do it well; I had two techniques; one was to fix customers through eye contact as they were approaching the counter, and the other assistants couldn't understand why they all came to me and not to them; secondly, I had a little notebook in which I put useful record numbers so that when asked, I could find it quickly, and sold quickly; I suspect I earned more commission than anybody else there; I was asked to see the personnel manager before I left for Oxford, and he invited me to come back afterwards; I enjoyed selling records as I'm very fond of music; that is one thing I owed to my mother; she played Debussy a lot and she was trained during the Second World War at the Wigmore Hall; I still think of her when I hear certain Chopin nocturnes as she used to play them and Schubert intermezzos

33:55:14 I have a vague memory of sitting with my back against a pillar in an upstairs classroom in Alcuin House School, aged about seven, singing; I had a very good voice and a good sense of tune; both my parents used to sing to me as a very small child, and I can remember what they sang; I was not taught the piano, I wish I had been, but my parents were very sensible and didn't force it on me; when I was about fourteen I expressed an interest in learning, and my Uncle Geoffrey paid for me to have a year's lessons at Merchant Taylors’; I didn't make much progress, not because I didn't enjoy it but I was very busy with 'O' levels and didn't have the time to practice; I did develop a love of music at the time when long-playing records were coming out; I initially started off buying 78s and used to run between bus stops to save enough money to buy a record at the end of the week, as I was allowed to keep any travel money that I saved; I liked obvious things like 'Greensleeves'; we had neighbours called Frank and Nellie Robinson who were extremely good to me; my mother used to go and chat with them in the evening and eventually I was allowed to go with her; they had a long-playing gramophone where I first heard Grieg's Piano Concerto, and I fell in love with that; we had concerts at Merchant Taylors’ which were held at Watford Town Hall for which we could get free tickets; I picked up most of what I know then; later I went to the Proms and I am going to six of them this year

37:10:10 I never work to music as I find it too much of a distraction; I am very interested in the history of music but it's not well written about; neither it nor the history of painting is set into context; the Robinsons were very influential; he was a self-made man which was a term of abuse for my mother, but he did very well; he worked in Kodak which had a huge factory in Wealdstone at that time, and made a lot of money; he epitomised prudence and success in my mother's eyes even though he was a self-made man; he was financially secure, and that is what she admired; I think he was in love with her - in fact he made one or two propositions to her which she rejected; she was giving the wrong signals as usual; I think that Mrs Robinson, a very nice woman, once caught her husband with his hand on my mother's knee; my mother went to see her next day and apologised, and offered to stop visiting; Mrs Robinson was secure enough to reject that suggestion, so my mother continued to go there; my father, when he was not being successful when I was about fourteen, had a dream of going to New Zealand and starting a new life; we were all set to go and Frank Robinson came to the house and told my mother not to go, and she agreed and refused to go; it was probably wise as it would have been a disaster; when my mother went out to work she needed to drive; she had taken lessons before the War but she nearly drove a hole in the back end of our garage, and my father discouraged her from driving thereafter. However, when she began going out to work she decided to learn to drive properly; she had a driving instructor, Roy, who was about ten years younger than her; the inevitable happened, she had an affair with him and separated from my father; at that stage I stayed with my father, though a bit torn, and she went off with the man; later on, her sister, Margot, noticed that my mother had marks on her face; she asked what had happened and my mother said it was caused by fat spitting up from the frying pan, but it fact he was knocking her about; by that time she wanted to leave him and went to live with her sister. Generous as usual, she had lent the car, a Morris Minor, to Roy, and the strategy was to get this car back; he lived in North Harrow; my father loved this sort of thing and had a huge collection of detective novels, and we devised a way of getting the car back; it was parked outside Roy’s parents' house where he was living and we had a duplicate key; we drove up together, I got into my mother's car, and we both drove away; I saw Roy in the front room astonished at what was happening, but he was too late, we had gone; Roy was a reasonable enough chap and for a time I used to go up to Selfridges with them; eventually he made it clear to my mother that he didn't want me in the car, so I then went to Selfridges with my father; after my mother left him she got a flat in North Kensington near her shop; eventually, Uncle Geoffrey bought her a little cottage in the same area; she was happy living on her own and became enthusiastic for encouraging discontented wives to leave their husbands, saying she had never been so happy as when she became independent.

45:37:09 Because of the instability at home, Oxford was a refuge for me and I used to stay up in the vacations a lot rather than go to one or other home; in another sense, I had the same fear that my mother had of slipping socially; I had seen them both slipping and I was determined not to; the only way out of that was passing examinations; for a time I lived with my father who eventually married one of his assistants, Doris, a very nice woman; they were living in a low-grade suburb of North London and I thought I am never going to sink any lower than this; you will obviously realize that I have absorbed all the class-consciousness that my mother had, but British society at that time was very class-conscious, particularly in the suburbs; yet work was not an escape for me, as it had been important for me at the age of five, as shown in the school report; my parents were perfectly happy for the first ten years, so I did not need to escape into work. Enthusiasm was, for whatever reason, built into my temperament from a very early age.

47:46:06 On teachers, I should start with Miss Dalgleish at prep school, who was a very good teacher; then there was Miss Keast, who was a fascinating woman; initially she terrified me as she had a disability which caused her to quiver; this was probably one reason why I had a term off from school as Miss Dalgleish was ill and Miss Keast was taking over the form temporarily; she also had money spiders in her piled up hair, and children are very frightened of things like this; however, they were both very good teachers, as a lot of unmarried women were in those days; D’Arcy Yeo, the Headmaster, was also very good though a bit of a sadist; he used to pull pupils' hair and hit them on the back of the head, though he never did this to me; I got into Merchant Taylors’ and was then on the science side, perhaps because I was quite good at maths; after slipping in rank-order in science subjects, and hating physics, especially science practicals, also being no good at geometry. I had never been accustomed to moving towards the bottom of the class, and felt I must do something about it. After three years I realized that another boy by the name of Harrison had moved from the science side to arts; I asked him how he did it as it was rarely done and the school didn't like such late transitions. He didn’t discourage me, but my parents were against me switching as they thought it was a bad career move. However, I managed to persuade everyone and did switch; I was immediately in my element, I was good at Latin still, as I had inherited that from the prep school; I went first into the Classical Lower Sixth, and then into the first year of the Classical Sixth, and thence into the History Sixth and the master who ran that was Alex Jeffries, an avuncular, very kind man, who was really a father figure for me; in fact, long before I came under his tutelage I had got lost in the school, and couldn't find where I should be and at what time; I stood outside the masters' common room and looked for somebody who looked friendly, and he was the one I asked for help; he was a good teacher, not high-powered intellectually, but inspirational and encouraging; he encouraged us to give talks to the class, which I did; he was also extremely tolerant, which my father was not, and I admired that; he was a veteran of the First World War; I remember him describing what it was like to be an army officer at that time, and he described the guns; he banged on his desk to show us what gunfire was like; he described how at one point he was trying to lead on his troop and couldn’t understand why nobody moved: they were all dead; it was very vivid and he was a brilliant teacher in that way; another good teacher I had in history Guy Wilson, who is still alive; he was very fresh from Cambridge, self-critical, and he started by giving us notes which we wrote down; at the end of the first term he realized that the method was not working and I think he changed to talks; it was he that made me into a Victorian; we read Monypenny and Buckle on Disraeli and Morley on Gladstone and I got hooked; I was the only person in the class who liked Carlyle's 'French Revolution'; I had a brilliant English teacher called John Steane and he was an opera buff as well; he was a homosexual I now realize and was very empathetic, totally inspirational, and a devotee of F.R. Leavis; in 'A' level English you had a piece unseen to criticize and I remember a piece of poetry from D.H. Lawrence about a child sitting under a piano on a Sunday evening and hearing the humming of the strings; we would see this blind and be asked to comment on it; in my comments it suddenly became apparent to me that I could have ideas of my own that weren’t derived from reading what others had written. Steane was very good in that way; in another episode where I still think that I was right, we had a passage from Nashe the Elizabethan author, describing the disembowelling of a man who had committed treason, and the heart was taken out "like a plum from a porringe pot" I remember; I said in comment that this was a terrible image for us but would have probably been less so at the time because in those days they’d have been more accustomed to brutalities of that kind. Steane said that mine was not a legitimate comment because my point was historical and not critical; it was that sort of discussion that we had and was very inspirational; I had another very good English teacher called R.B. Hunter who taught me for Wordsworth which was one of the set books; we read 'The Prelude', and again I got quite hooked on it and I wrote what he thought was a good essay; he wrote at the bottom that I could actually go to Oxford or Cambridge, and that was the first time that anybody had said that to me; eventually I got a scholarship to St John's - the Sir Thomas White Scholarship for History; with the other candidates I went up to the Merchant Taylors' Hall for the interview and remember it as a funny occasion; someone on the interviewing panel mentioned me writing such and such in my essay and I said "Did I say that?", and they all laughed because I was incredulous that I could say such a silly thing; we eventually went as scholars for a dinner at the Merchant Taylors' Hall, the first time I had ever been to a grand dinner, but I did not then realize that you have to be careful on such occasions about what you say; it was at the time when the British were having trouble in Cyprus and some government minister had said we would never leave it; I said to the man sitting opposite that I thought it a silly thing to say, only to be told that the Minister was his brother-in-law; I suppose I was pretty opinionated at that time, perhaps insufferable to some. Anyway, that got me to St John's, after doing my two year's National Service, and my friends were there; we sat together at the Scholars' table and I had a set of friends ready-made

59:11:24 I was hopeless at sport at school because of myopia I couldn't see; I had glasses from the age of eight; I remember coming back from the optician with the glasses and my mother saying that I looked funny wearing them; I was terribly upset and I hated wearing glasses; it took me years to get used to them, and it meant I was hopeless on the sports field even if I had any aptitude, which I didn't. For that reason I went in for life-saving (i.e. swimming) instead of cricket; if you didn't like cricket you could do life-saving; I had no enthusiasm for saving lives but every enthusiasm for getting out of cricket; I still have a friend (Nigel Williams) where the bond between us is a mutual hatred of rugby football on Saturday afternoons in mid-winter; I remember when I changed from the science to the classical side of the school, one rather patronizing young man called Willoughby, now deceased, said that everybody in the form (Classical Lower Sixth) did something distinctive; I took up calligraphy and produced a huge piece which I still have but didn't do anything else; I worked very hard academically because I had to justify having moved across the school from science to arts.

1:01:26:02 On religion - I was confirmed and am rather ashamed of that fact now; the whole family were anti-intellectual and anti-religious, they didn't like anything involving pretentiousness or falseness; they thought people who went to church were hypocrites. My father’s greatest fear was that I might become a ballet dancer or a Roman Catholic. None the less, being confirmed was a rite of passage in your upward move in British society, or at least in your attempt to stay in the same position socially; I went through a fairly religious phase as teenagers tended to do at that time as actually the Church of England was quite powerful as an influence in Public schools then; I struggled for some sort of faith but never found it; I greatly admire Cormac Rigby who was a contemporary at St John's, who would go off to mass regularly and took David McLellan with him; David became a Roman Catholic as a result of his influence I think; at one stage I asked Cormac how I could learn more about Catholicism and he told me of the Catholic Truth Society; they sent me leaflets among which was a booklet titled 'The Pope is Infallible', and that finished me off; my parents, of course, were terrified of my becoming a Catholic, but fortunately the C.T.S. sent its propaganda in plain envelopes; the only thing that was worse was becoming a ballet dancer; they were very worried that I might have become that as I got enthusiastic about ballet at about fourteen, when the Robinsons used to take my mother and me to the Royal Festival Hall to watch ballet; I loved it, and still do; I have always remained an agnostic, not an atheist as not militant about it, but I've never seen evidence for religious belief, and if anything, being an historian has turned me the other way; one small episode at school is relevant; in the Classical Lower Sixth where I was for a year they made a clepsydra, a water clock; in the Great Hall at school there were apertures in the ceiling which could be opened in the fencing loft above it; there was a plot at the end of the Summer term in 1954 for putting a clepsydra above one of these holes and attaching to the arm that tilted when a certain amount of water had gone out, a toilet roll, which then plunged down, much to everyone's excitement, into the Hall in assembly after prayers; we organised this and it worked like a dream; we meet every year to celebrate this event and I was appointed historian of this group about twenty years ago - they call themselves 'The Rollers' - so I wrote a history of the event; there were many contradictory accounts from the people involved; some said the toilet roll had fallen on the Headmaster's head, which it didn't, others said that one of the monitors tried to tear off a strip from it and failed to bring it down, so a memorable event; at the end of the piece I wrote on it I said that after twenty years, with all the people present, we don't remember exactly what happened, or even what day it was; noting this, I asked what credence could one give to anything that was written even 20 years after the event; one of my contemporaries in that group, a non-conformist, objected to this, so I removed the direct reference to the Bible that I had given as an example; I have never felt any temptation towards religion, and when I listen to religious broadcasts on the radio wonder how anyone can believe that junk, it doesn't influence me in the slightest; I'm attracted, of course, to the buildings and the cultural significance of it, as is Richard Dawkins; my only reason for having accumulated a large collection of biographies of Bishops is that they are valuable for understanding the Victorians, not because I am interested in religion as such

1:07:53:11 On National Service - I was eighteen when I went to Malta; I was in the Royal Signals; I do wish my parents had kept my letters as I would love to read them now, I wrote back at least once a week to them, but my mother threw away everything once she had read them; I do still have the letters I received from them; it was a most extraordinary experience; for the first six weeks we were simply treated as irks, as they called ordinary soldiers, and were pushed around the drill square; it was like a nightmare, a most peculiar experience, but also at times extremely funny; it was like being a schoolboy again, laughing at masters behind their backs; we had a Corporal and a Lance-Corporal running our particular section, and I remember we were required to clean out the lavatories with our hands - "cleaning out the bleeding shit", crude language that I had never heard before; Keith Thomas says the same about language heard when doing National Service; I remember thinking that it was a ghastly situation that I would have to get through somehow; there was a lot of talk at night after the lights were out, some of it extremely funny; after that six weeks we went on to OCTU (Officer Cadet Training Unit) where we were trained to become an army officer; that was quite a memorable experience because when we went from one side of Catterick to the other for this training it was absolute hell; we were told we had to get the barracks, called 'spiders', in order over the first weekend, absolutely spic and span; we were driven from pillar to post; I remember seeing one chap cleaning a window with the cloth in one hand, and an Officer coming and saying "Both hands, both hands"; we were told that if we felt we couldn't stand the pace we could sign ND (non-desirous) forms to opt out from it; I felt at times I would like to but didn't; eventually, on the Sunday night, at the end of the barrack room I suddenly heard a lot of laughter, and it turned out to be all a hoax; the next course above us had dressed up as officers having us on; the realization never left me of the impact that the mere wearing of a uniform can make. We did a lot of high-powered drill in our training as officers, but it was never as high-powered as at Merchant Taylors; we then went up for what was called WOSB - War Office Selection Board, and you had to do things like carrying a barrel across a stream, directing a group of people, and having projects for getting from A to B, also interviews; I passed that as I was expected to do, as public-school boys didn't fail WOSB; actually I was jolly glad I passed, as I wasn't sure I would; then you went on to Mons, another six-week course near Bisley; again a lot of drill, but I learnt to lecture which was quite a good thing to do; in my indexing system I use a lot of abbreviated words and they originated from the abbreviations we used in the army - 'accn' for accommodation, for example; eventually I got commissioned and I invited my parents to the commissioning parade in Catterick where we had been for the last six-week part of the course; I asked my mother to make sure that my father was properly dressed; my father had embarrassed me when visiting my public school as he just didn't bother with his appearance whereas my mother was perfectly dressed; unfortunately my father saw my letter to my mother and took great offence; I then wrote a tactful apology to him and he came properly dressed; I was then free to go off to Malta in the Signal Squadron and ran the military transport section there; there were five or six Maltese drivers, all middle-aged, and few Maltese other ranks with some English; again I was struck by how easily one is influenced by one's environment; we despised the Maltese and believed them incapable of running things; this was the time that people were saying that the Suez Canal couldn't be run by Egyptians; we called them 'The Malts', and I just inherited this from my surroundings; I didn't think this at first but, like a chameleon, just adapted to my environment; I was in Malta from 1957-8; I learnt to drive then and still don't have an English driving licence; it was ludicrous to run a transport section without being able to drive; I learnt a lot of value there; it was a most interesting place; I also learnt that I could run things; I actually went into the Post Office section of my father's shop shortly before going into the army, and picked it up quite quickly, learning the most complex business of issuing a money order payable abroad; I taught myself Italian in Malta and did the Italian special subject later; by the end of my National Service knew Malta very well, and in many respects enjoyed it though I wouldn't say everybody should do it; another side was that I was terribly immature, like my mother, in sexual matters; I remember one of the officers in Malta Signal Squadron was fascinated by prostitutes; there were a lot in Malta and occupied one of the well-known streets in Valletta; he took some of us to one of the places where you met these women, and I was appalled at the very thought of it; it never occurred to me to go to a prostitute; I was really very innocent in that sense, though on my return to England my mother thought I was much more grown up than I was; that is a disadvantage of being an only child and going to a single-sex public school; I had friends, both male and female, but there was no sexual component; my work on 'Sex and the Victorians' could be seen partly as self-discovery

1:19:53:08 I was twenty-one when I went to Oxford; as undergraduates we thought we were terribly mature, but we weren't; I went to Selfridges from January to October 1958 before going to St John's; there I started with Keith Thomas, Howard Colvin and Michael Hurst as my three College Tutors; Howard Colvin was a very scholarly man, and it really was a case of absorbing scholarship by osmosis; he was then just making the transition from being a Mediaeval historian to an architectural historian and he had rolls of plans on the shelf in his room; he was very interested in the photographs I took as I was quite good; I had taken photographs in Malta and elsewhere, coming back across Europe to England through Italy and Austria; he particularly liked one I had taken of the fan vaulting in Wells Cathedral; he wasn't a teacher in the sense that he wasn't really interested in teaching, as such; he knew how to write, but I didn't learn that from him, but he was a good influence and I was just bursting to learn; coming to Oxford was just paradise to what had gone before, so I was keen to get the utmost out of it all; Costin, the President, who taught us Voltaire's letters; the philosopher Mabbott took us for political thought; I did very well in Prelims and went in for the H.W.C. Davis Prize and came proxime to Prys Morgan, who got it; we were both in St John's which was getting a reputation for History; I didn't encounter Keith until my second year for the 'Middle Period', and we didn't really get on; I thought he ought to know that I didn't need pushing and knew what I was doing, and he was very much the martinet; I worked out that you didn't have to do continuous British history but could select, so I refused to do anything on the seventeenth century, which was silly because he was the specialist on the period; he forced me to do a collection on that period, to write a few essays, and it was the only time I borrowed someone else's essay and copied it; I wrote an essay on Cromwell about whom I knew nothing; he was a martinet for the best possible reason as he wanted his pupils to do well, so we really didn't get on; however, we didn't have a row, and I respected his intelligence and range; his lectures then were quite famous on political thought, and they really were inspirational; as a lecturer he was awfully good; the person who really inspired me was Jill Lewis at St Anne's; she taught me for the Italian Renaissance special subject, and she took an awful lot of trouble; it you sent her an essay she would scribble on it and you really felt she had read it; I never felt that any of my St John's tutors ever really read my essays; I was either paired with Cormac Rigby or Prys Morgan for tutorials and one or other of us would read out his essay; my essays were always rather long, especially for Howard Colvin; I did suggest to him once that I hand in my essay, that he read it and then we would talk about it; but he thought he would have to give up his research day in London to do that; I vowed never to say that to a pupil; later faced with the same dilemma, I tried to comment on each person's essay, but eventually only did so for the person who had not read out his essay as it was just too time consuming; as an undergraduate I thought, quite wrongly, that my tutors were lazy; they were not, but were following the Oxford system which only allowed a certain amount of time; Michael Hurst, who was a controversial character and eventually pensioned off, treated me very well and was a good Tutor; Paul Slack told me that in a tutorial, Michael said that as he was being particularly original, would Paul please take down what he was saying; it was that sort of conceit that he suffered from and in the end I had to break with him; he wanted me to be a disciple and I did not want to be that; there were other lecturers, like Isaiah Berlin, who was wonderful; I had a syndicate with Prys Morgan and we divided the lectures that we wanted to go to between us, and we duplicated notes and gave them to each other; I learned a lot from Prys who was a highly cultivated chap; I envied his cultivation, as his father was a Professor of Welsh in Wales, and he had breathed it all in; Cormac didn't like him because he thought he was a fraud, and thought, perhaps rightly, that I was too much overwhelmed by Prys. In my second year I won the Gibbs Scholarship which was a godsend, as it gave me £300 a year for three years, which was a lot of money in those days; that started off my book collection; I wrote to Keith to ask where he got his books and he told me to give my name to a number of booksellers, that they would send their catalogues and I could buy from them; I did that for a long time; it involved a lot of work looking through catalogues, but I would go on expeditions to places like Ilfracombe, where the Cinema Bookshop at that time was a gold mine; all my Victorian biographies of bishops have come from bookshops in cathedral cities; at that time Keith came into his own as after I won the Gibbs Prize he realized that I had something; he encouraged me, and invited me to meals; he and Michael Hurst didn't get on as Michael was jealous of his influence

Second Part

0:05:07 I went to St Antony's first as a graduate student; I had got a First; I remember picking up Cormac to go to our vivas; when I went into mine I expected to get a lot of questions and I didn't get any at all; I can't remember any details but the whole board was there; they simply asked me what I was going to do in graduate work; I learnt afterwards that I got the best modern history First in my year; I had already been interviewed at St Antony's and remember Theodore Zeldin asking me what I would do if I didn't get in; I said that I would swallow my pride and become a schoolteacher, and if I had done so I would have modelled myself on Alex Jeffries; anyway, I got in and Prys came there as well, writing about Mediaeval Calais, Keith Robbins from Magdalen was doing work on the First World War, and I was doing nineteenth-century Temperance; the idea of writing on temperance came from Harry Hanham in Manchester; one of my few skills is writing a good letter, and someone suggested writing to people whose work I admired and see if they had any ideas for good research subjects; I wrote to Hanham and Kitson Clark in Cambridge; Hanham said that something that needed to be written about was the Temperance Movement; I immediately saw the potential, as it was obviously so important in Victorian society and odd that it had not been written about; that was my first book, Drink and the Victorians, but it started as a D.Phil. thesis rewritten and drastically slimmed down; my disability has always been writing too much and it had to lose 100,000 words; it was published by Faber, and the person who arranged that was the well-known literary agent, Michael Sissons; I had written an article in History Today on temperance tracts in 1963 and he had seen it; he invited me to lunch and said that if I ever wanted to publish a book he would help me; I sent him a typescript and he took it to Faber; they said that it would have to lose 100,000 words but they would publish it if it did; they published it as Drink and the Victorians in 1971; I had published a lot of articles before that, partly because I wanted to offload some of the vast amount of stuff I had collected somewhere else, so that I could refer to it in footnotes and not have to include it in the book; I was launched by that stage but I broke with Michael Sissons; I had written an essay on 'Moral Reform and State Intervention in the Victorian Period' for a book of essays edited by Patricia Hollis called 'Pressure from Without', published in 1974; Edward Arnold offered me £50 for it and I asked Michael if I should accept it; he suggested £100 was the price I should ask and said he would write to them; Edward Arnold stuck to £50 and then Michael had the cheek to take £5 off that as commission; I was furious; I didn't say anything but I thought from that moment onwards that I didn't need an agent

5:40:00 On my indexing system, I don't know where I got the idea from, but certainly by the end of my undergraduate days I had quite an elaborate card index; I had an index of quotations which I learnt off by heart, and another of dates; I knew an enormous amount in those days; that was its initial function, but I got used to shuffling around cards although I hadn't developed the present arrangement of facts on cards and bibliographical cards; that happened from the beginning of my time at St Antony's; I remember going to see James Joll, the Senior Tutor, and asking how you did research but got nothing from him; he said that if he kept a card index the cards would fall about all over the room. This rather shocked me as I had thought I would get some guidance on how to do research; so I invented the card index system for myself; it somehow grew out of the undergraduate card system that I had already developed, though it had a different function; Beatrice Webb's ‘one fact one card’ as outlined in her ‘The art of note-taking’ at the end of the Webbs;’ Methods of social study, was an influence, but I don't know that I had read that before I started up my own system; I don't remember any moment of enlightenment, but stumbled on the method for myself and then found it validated by her; I did not know about Keith Thomas's envelopes in those days as he didn't talk about them; he was very well organized in comparison to me because while I was just looking through booklists wondering whether to buy them, he was looking through for references that would be useful and slipping some of them into his envelopes; I never thought of doing that, so in that sense he was far more efficient than I was. I think Peter Burke was quite an influence at this point; Peter was very intelligent, a highly intellectual person, and we used to talk after dinner quite a lot; he said that the important thing was to keep your horizons very wide when researching, and this is what Keith does; I always try to do so, and the index started off solely on temperance but eventually diversified and became a general index on everything; temperance is now only one drawer of fifty, and there are all sorts of sections on political parties, Parliament, etc.; in all there are over 1,000,000 cards, many of them duplicates, as material often needs to be indexed under several heads; in the beginning we did not have Xerox machines - the first one I used was in Nuffield College where I went in 1964; at that point I decided it was absurd typing out one card several times, which I initially did, and got into the habit of Xeroxing cards on to foolscap sheets, and then I would cut them up and file them; it took ages and was frightfully boring; it all evolved organically from that; I never measured the time it took, but I worked extremely hard, all hours of the day; I did not take off weekends but treated them as work days; I enjoyed it; it was partly ambition and that had developed at school; when I was at St John's I discovered that I was abler than I thought, winning those prizes helped in that, and I then looked out of my window on the second floor straight into the Senior Common Room; I saw a really rather nice panelled room with a big chandelier over the centre table and I used to see Dons going in after dinner for dessert, and I thought to myself that that was a nice life; now I am an Honorary Fellow there, quite often having dessert in there, I think I've made it, but I never planned to be a Don as it then seemed flying rather high; I just wanted to do as well as I could and I remain surprised at having been a Don for I never thought I would

13:59:10 I did encounter problems of finding things as my indexing system grew, and my solution was constant subdivision, reshuffling and rearranging, so there were smaller categories in which one could find things; of course, it is nothing like as efficient as a computer, so that problem has now gone away; filing obviously took longer and longer, and looking back, it was becoming a real trial; that is why I am so glad I gave up filing; the flexibility of computers involves risk in the sense that the stuff isn't secure, although in some ways it is more secure if you take copies of it elsewhere; I now have a backup on the University system; looking back, I did predict to myself that computers would eventually sort out my stuff for me and before the Access Database was drawn to my attention, I was just printing cards from the computer; as I had kept the information in its computerized form so that when I got the database in c.1997 I was able to transfer 5-7 years of information into it; I started making cards from the computer in 1992 and foresaw that it would become possible to use the typed information in a different way than just printing it out; the same happened with laptops because I thought that there would come a time when people would carry computers around with them; I got one of the earliest portable computers in about 1986; it is still in the garage as I think it might have enormous second-hand value at some stage; I took it from archive to archive when I was working on the history of the University; it had a small screen and no hard disc; I wrote an article in the College magazine about how computers came to Corpus; I wrote it because I just thought that we would forget what it was like in the early days; I re-read it the other day and thought that nobody could write this now because they have moved on and forgotten what it was like; I interviewed four or five Fellows of the College for that

19:38:08 On the use of the index, the important thing is to enjoy writing; the agony of writing which I remember when I was doing my drink book is not being able to find stuff; it adds an additional layer of painful procedures, so if you can make everything instantly accessible it not only ceases to be a chore but becomes a positive pleasure; the initial impulse for moving on to an Access database was to remove chores and to make it easy to assemble factual material in the order that you wanted when you came to write, then the process of writing becomes pleasurable and if writing is enjoyable, I think you tend to write better; the process of writing is a continuous process of discovery; you don't know when you start on a chapter what you are going to say, but in the course of writing it, you discover; in my case ideas often tend to emerge from unexpected juxtapositions; you think about one thing on one record, then look at another, and suddenly realize that they are related; that in a sense could be called ‘an idea’; so the process of creating is also exhilarating and of course a highly personal matter too, whether it is good or bad it is yours; that is why we are so different from the natural scientists; though all sorts of personal factors shape scientific discovery, the personal element is still stronger in the Arts; anything that I write, good or bad, emerges out of my personality, experience, and my peculiar combination of reading, so you get all the satisfaction you would get out of sculpture or painting; it is highly creative; it is also attractive to me because it is cumulative, and on the whole you get better as time goes on; it requires a knowledge of human nature, of context, and of how things happen, so I think that, unlike some natural scientists, on the whole historians get better as they get older; the cumulative aspect relates to collection; I am collecting things all the time; they are facts, ideas, or insights, and the cards are substitutes for collected postage stamps; I am very competitive as well, so there is also that incentive; I think that in research one starts off with rather low motives and these motives improve as life goes on; initially what I was fighting for was security and success in some sense, but then the process in seeking those things becomes itself the object; the ambition and lower motives get overlain by a scholarly motive, so on the whole one is probably a nicer person later on in one's career than one was at the outset.

25:37:03 I now write on the computer and couldn't think of writing in manuscript, I want my material to be instantly flexible; it is much easier if the cards are there in digitised form so that I can arrange them in the right order; before I was able to do that, I would physically arrange cards in an order that would give me my initial text, but then very frequently one would rearrange them once they were on the screen; the big virtue of computers is that you can reshuffle the stuff; that flexibility you don't have when writing in manuscript; I never understand people who can use a computer saying they always put their first draft in manuscript because that's the time that you move the stuff around most; maybe some people are much clearer-headed than I am so they know exactly what they are going to say when they start writing; I don't; the Warden of Nuffield used to say to us ‘Get something down, it doesn't matter what it is like, get started’; I do that; I write at any time but I am a morning person and can't usually do serious work after about nine o'clock at night; in the past when one had to type I used to go through seven drafts of anything I published; now I have no idea how many drafts I do, I don't print it out as I go along, I just do it all on screen; I couldn't say I always had my best ideas away from the desk, but quite frequently will wake in the morning to find something has become clear that wasn't so before, just through sleeping on it; I always used to carry cards around with me so that I could write ideas down whenever they came to me; the great attraction for me of writing contemporary history (in my two volumes in ‘The new Oxford history of England’)was that, for at least a decade, any casual conversation could turn out to be academically fruitful; when I went to the dentist, for instance, I might ask why and how he became a dentist; my mother always used to ask me as a child when I would stop asking questions; all children do that, but I have sought to perpetuate that childish trait into extreme old age; I am inquisitive by nature, and being an historian gives you every excuse for asking questions of people or raw material; someone criticised me for being naive, but all historians should be naive, and should approach reality with surprise; why are things as they are, and why do people respond as they do, and couldn't it be done some other way, or whatever; to that extent I am a disciple of Wordsworth; I do think that young people have a freshness of outlook which one really needs to try to retain; to appear worldly-wise and all-knowing is wrong in my view, one should be learning all the time; I have never minded asking people questions and that is one reason why I have done a lot of interviewing

31:48:14 The first serious interview I did was with Douglas Veale, who was the Personal Private Secretary of Neville Chamberlain when he was Minister of Health; he was a retired University Registrar, and Fellow of my College; I did two interviews with him about Chamberlain; he was very incisive, very clear, as civil servants can be; this convinced me that it was a technique worth having; this was in 1967-8 and at that time Paul Thompson was starting, and I used to go to History Workshop meetings to hear him; I was a follower but not a disciple, as I felt he was too bitten by social anthropology and not sufficiently critical of the stuff he received; none the less, he got ‘oral history’ off the ground; I went on a BBC course that was organized by him about interviewing people; it was good for me in a number of ways; I'm not an extroverted person but interviewing made me much better in company; I got used to putting people at their ease and getting them to talk; I think it was good for me in a general way; my interviewing really originated with my father giving me his Grundig tape recorder (very expensive at that time) in about 1959; it was a huge thing like a suitcase, and I remember wondering if I would be able to lug it around when I was sixty-four; I used it for recording music off the radio; I recorded the first tutorial I ever gave, as the tape starts with Keith Robbins (who lived in the next room) looking round the door to tell me that the students were coming, and there follows a dreadful tutorial with two students from St Edmund Hall; I talked all the time as I was terribly nervous, as a young tutor is, whereas the essence of being a good tutor is to let them talk; I did learn from listening to it; on one of the BBC courses we were sent out to interview people, and I interviewed a cockney woman in Camden Town in her kitchen; we played the interviews afterwards to the group and it was a dreadful interview as we weren't connecting at all; I did get better at it and eventually did a big project interviewing suffragettes and feminists; that set is now at the London Metropolitan University in the Women's Library, though the Library is in danger at the moment; it is called the ‘Harrison Collection’, and contains about 200 interviews, some very good; we made a radio programme for Radio 4 about three months ago with Peter Snow presiding, where extracts were played; there was a wonderful one of Maud Kate Smith, who was on her death bed in some old people's home, talking about being forcibly fed; she had a bright, chirpy, voice, and talked in such a cheerful way about this ghastly procedure; it came over brilliantly on the radio and there was a close following on Twitter as a result; she died soon after I interviewed her, but at that stage she was still not saying who was involved in her sabotage attempts - she was trying to destroy the canal system by blowing up an aqueduct in the Birmingham area; there were many other episodes in that project which were quite memorable; people would burst into tears during interviews and I didn't know how to cope at first, but people are prepared to talk more freely to a stranger on very personal matters; I did a lot of interviewing for the history of the University as well; furthermore, oral history emerged somewhat more centrally for that, as I organised 64 seminars on the history of the University - Keith Thomas gave one of them - and I did word-for-word transcripts of them; we not only had the paper but also the conversation afterwards with names attached; they are now quite an important record of what the University’s elite were saying in the late 1980s about the University's recent history as they themselves had observed it; they were quoted in footnotes in volume eight of the History; the seminars became ‘an event’ that people came to and took care over what they said, though I don't think there was distortion as people became involved in the event and were not thinking about what would be said of them twenty years hence; seminars were also useful in getting chapter writers started, as they would be expected to address the relevant seminar; I also interviewed people like Isaiah Berlin, Max Beloff, and so on, just to try and understand how their subjects worked; but interviewing is so time-consuming that I didn't use it much for the New Oxford History volumes, I would never have written them if I had; I interviewed a dentist called Downer about the history of dentistry, which interests me, and also Cicely Saunders, the founder of the Hospice movement, and she was a marvellous woman; I would like to have done more interviews but decided it was just too time consuming; you can't use it unless its transcribed and that takes seven times as long as the interview; it never occurred to me to film interviews; in 1969 some very good students of mine said they wanted to write some history of their own; Trevor Aston was there then with all the accoutrements of 'Past and Present', he liked the idea, and we made a tape recorder available so that they could take interviews, though a number wrote in manuscript; they interviewed College employees and found that far from being envious, they enjoyed being close to the privileged; this seemed very odd as this was the period of Marxism, class-consciousness was the thing, the Labour Party was going places, so these people were oddities; in fact they were a lot more sensible than we were but we did not know it at the time; the project worked very well, but I am surprised how much time the students were prepared to give to it as it didn't pay off at all in their degree result

43:53:18 I was frightened of Nuffield as a Junior Research Fellow (1964-7); I applied to go because it was the place to be if you were a modern historian; it was then, and still is, a highly professional place, very competitive and very serious; that was why it was disliked in the rest of Oxford; there was no pretence of amateurism at all; it was very good for me as it exposed me to political science and sociology, and to a certain extent to social anthropology; there were some very interesting people there including Rod Floud, Patricia Hollis, Gareth Stedman Jones, Robert Currie. Raphael Samuel came into discussion groups we had, Max Hartwell was extremely encouraging to us all - it was quite an intellectual hub; I wrote an article with Patricia Hollis in the English Historical Review for 1967, and we edited Robert Lowery's autobiography together, and published it with Europa in 1979; I found it and showed it to her; she was working on the Unstamped Press movement in the 1830s and said it was important; I suggested writing an article on it together, and then we edited the autobiography which was published in 1979; that was the atmosphere in Nuffield in the mid-1960s, as there was a lot of inter-fertilization; another person I ought to mention is John Walsh; he was a wonderful man, very encouraging, a historian of evangelicalism and Methodism; the first time I ever met him he simply looked round the door of my room in St Antony's and invited me to a seminar on the history of religion that he was running; I was very flattered that he should bother to ask me so I went; he used to send me slips from the Bodleian Library with references to temperance that he had found; I was not the only graduate student deeply indebted to him; he was a friend of Keith Thomas, and they were both very encouraging, which you need as a graduate student; the first year, Peter Mathias, my supervisor (in Cambridge), left me alone; he then said I should start writing; it wasn't before time, as in retrospect I thought he should have got me writing earlier; he was a very good supervisor, very encouraging, and conscientious in reading my stuff; I used to go over to Cambridge on the railway that then existed between the two cities; my first bit of writing turned out to be the second chapter of 'Drink and the Victorians'; he wrote at several points on the text that I had been "uncritical" of the evidence; this frightened me to the extent that I wondered if I would be any good as a historian; I remember sitting in Queen's College in Cambridge, where I had a bed for the night, wondering if my venture into becoming a historian had been a big mistake; but he was encouraging and very supportive, and I needed to be told that; what with him in Cambridge and Keith in Oxford I was very well looked after; in the end Peter used to call me a Stakhanovite, I just flooded him with chapters on drink, and finally took off from him in a way; I was always a social and political historian, not (like Peter) an economic historian; I was never very interested in economic history and sociology was the subject that interested me; there I got a lot of encouragement from sociologists in Nuffield, particularly Chelly Halsey who was extremely encouraging, a very nice man, and eventually we collaborated in writing things for the history of the University; there were a lot of encouraging senior members there; Norman Birnbaum was there for a time, an American sociologist, and Jean Floud - she was my model of an intelligent woman, well turned-out, very incisive, and tough as old boots

50:06:23 Three jobs came up in the same year, 1966; the job at Queen's, which Ken Morgan got, came up first in 1965 and I wondered whether to apply; I didn't think I would get it and it would also get me tangled up with the Prestwiches, which I didn't want to do; Keith was not keen on the Prestwiches either; this is where Keith is so good, he advises you on your career, what to do when, that sort of thing; I think it was with his encouragement that I decided not to apply; then in 1966 three jobs came up at the same time, one in Oriel, one in Christ Church and one in Corpus; I was in for all three; I got a postcard from Michael Brock at Corpus, who asked me to call on him to talk about my future; naturally I went in my best suit at once; they did what now would be quite impossible; the Fellows invited me to dinner and I talked to several of them; I remember being grilled by Christopher Taylor, the philosopher, about Gladstone's drinking habits; they just offered me the job though I gathered afterwards that there had been a competition of some sort; Keith said it was a very nice College so I should take it; Michael Brock was very good at initiating me into the teaching process; I was a bit of a firebrand then, very much a Nuffield person and in some ways I have remained so; I didn't go for the amateurism of Oxford and the pretence of not taking work seriously; I remember getting into trouble with the College secretary because I was Xeroxing so much; at Nuffield you just took things like that for granted; that was where I started Xeroxing cards; I thought that attitude would apply in Corpus, but it didn't, and was rather disapproved of; I did enjoy teaching but there were three nagging things; President Hardie, the first I served under, was enlightened enough to say when I was invited to go for a semester in Ann Arbor in 1970, that I should go; I went, and was very much taken with the American teaching system - lecture based, course-paper based; I gave something like forty lectures on British history and liked it; I thought the American system much more compatible with research and publication; there was no fixed syllabus and you could teach what you liked; thereafter I was always an outsider as far as the Oxford teaching system was concerned as I didn't believe in it; secondly, I hated examining and didn't believe in the then four-class system; I do not believe that human nature is divided into four categories; a fortnight ago, I was invited to talk to a gay-lesbian society and said I did not believe in this bifurcated view that the world is divided into homosexuals and heterosexuals, nor did I think the category of bisexual was much good either; the world is divided into a spectrum from one extreme to the other, and it is no more divided into two or three categories in that sphere or into four categories of intellectual calibre; I felt that the pupils I taught were good didn't necessarily get the right marks, and people whom I thought incapable of getting Firsts, got them; that worried me; I had to pretend that I believed in the system, which I didn't think was delivering the right results, and that really lasted until the end of my career; it involved a certain degree of hypocrisy as you can't say to students that you don't believe in the system, you just have to pretend that that is the system and that's what you do; I liked the one-to-one teaching and I think I probably became a better teacher the older I was because pupils initially seem a bit of a threat, they are near one's own age and one wonders how hard it will been to get an essay out of them; Keith is a very sophisticated tutor in many ways, though I did not see that as an undergraduate; he knew that the tutorial was not an occasion in which one delivered information which was then absorbed, it was an opportunity for discovering your own thoughts and being able to convey them clearly to other people; the best tutor was not the person who knew most about what he was talking about, but often someone very different; there is an exhilaration in a tutorial to learn something from a pupil that you didn't know anything about; I think at first I was a bit overwhelming as a tutor, but I think I got better; I like young people, and like the opportunity of talking with them on an equal basis; I never made them wear a gown, and if they wanted to smoke in a tutorial I pretended not to mind, because it ought to be an equal thing; I hated lecturing, mainly because it is peripheral to the Oxford system which is tutorial based; I never really thought I knew the truth, so that lecturing was didactic, and I preferred the tutorial system in that sense as it is question and answer; you don't necessarily know the answer, whereas in an lecture people think you do; quite apart from that I am not a particularly good lecturer and not a spontaneous performer, and I think you have to have a histrionic flair to be a really good lecturer; I could never be an A.J.P. Taylor, for example, though I admire him immensely for what he was able to do; Berlin, still more so, he was a wonderful lecturer; I think Michael Howard said that an important thing with a lecture is for it to go through the brain, so that what you say is what you are thinking at the time, not to read out some screed; that is very good advice and I haven't got a good enough memory to do that convincingly; I was quite good at administration and could have had an administrative career, but I didn't want to because I had various relatives who doubted that through my research I would ever find anything, and I was quite determined to write things to prove them wrong; in the end I got the writing bug and loved it

1:00:39:02 On my wife - I got started as a graduate student before I met Vicky in 1964; we married on the first day that the Registry Office was open in January 1967; I was strongly against a church wedding and greatly disappointed her parents as they would have liked one; we were complementary, both in personal terms and academically; she was doing a D.Phil. in natural sciences and was working quite hard in the labs when we first got married; we didn't know how things were going to turn out, whether she would join me in some joint operation or was she going to have a career of her own; it was really Robert Maxwell who got her alerted to the fact that she is good at communicating; she is a very good writer; she is a meritocrat, unlike me, going to a grammar school in Workington and making it to Oxford through her own inherent ability, though her parents encouraged her; she went into the popularization of science rather than professional science; through a sort of osmosis I gained a certain confidence about writing in that area and she also gave me a certain scepticism about science; she is very sceptical about doctors, for example, which I had never thought about and just believed everything they said; I was like my mother who went in for the last operation that killed her, totally confident that it would cure her completely; I remember her waving as she went into Intensive Care at St.Mary’s Hospital, Paddington; Vicky and I are complementary in character; like her mother, she is very diplomatic, whereas her mother says of me that I am so open, and for her that is not praise; I think I have probably become a bit more discreet as a result of Vicky’s influence; she comments on my writing, but we are both busy and have had separate careers, so we are a marriage of opposites in some ways; we couldn't have had that if we had had children; two careers would have been quite impossible in that case; not having children was not by design, it just didn't happen, and the pattern of our life was in some sense determined by that; I have always been interested in children and am rather fond of them; I like trying to think myself into their ways of thinking; David McLellan's awfully good on this; he talks to his grandchildren and they are very logical; it particularly interests him, I see him quite often, and their way of thinking is attractive to a philosopher; I would like to be a child myself, and think it rather important to remain a child, feeling that the world is strange

1:06:42:19 A lot of people say that I am best known for Drink and the Victorians; it was my first book and one is always proud, seeing one's name in print for the first time; I really enjoyed it, and soaked myself in temperance, as it was not my world at all; I later learnt that father's father had actually preached temperance standing on top of a public lavatory in Hull; my father was always very interested in what I was doing but my mother could not understand it and thought it bizarre; I dedicated my first book to my father and wish he had lived to see it; it is a classic case of retrospectively discovering one's parents when it is too late; I never really knew him whereas I knew my mother all too well, but they were both very good parents in their way and I owe a great deal to them. Women's history was always messed up by militant feminists who were extremely tiresome; I am a feminist but not militant; militancy is incompatible with the historical outlook which should be balanced, measured, and I felt uncomfortable in this world and eventually got out of it; I was intending to write a big history of British feminism but I gave up because I didn't feel the climate was right; I did write a lot of articles and two books, but I didn't write the book I originally intended; I enjoyed doing the history of the University a lot and I think that if anything "made" me it was that, because I got known in the University for the seminars, and then handled this big volume, which wasn't easy but exhilarating and very enjoyable to do; although I only wrote three chapters of about twenty, I did have a grasp of the whole thing; probably the thing I have enjoyed doing most has been the 'New Oxford History of England'; I started writing my first of two volumes when I was working on the Dictionary and wrote the first four chapters in draft while doing it; then persisted with it in retirement and got it done; it was a real building operation and took ages, and it built on everything that I had done; it drew on the card index and all the newspaper reading I had been doing; I haven't said that teaching for the PPE course was very important in my intellectual growth; in a peculiar situation at Corpus I taught both PPE and history; PPE pushes towards the modern and I learnt a lot from political scientists; I did a huge amount of reading for my two NOHE volumes in the 90s and then started writing about 2003, and published the first volume in 2009; my name doesn't appear in its subject matter anywhere, and I think it would have been wrong if it did, though Paul Addison does feature in his history of the period; I also enjoyed it because I had been brought up on the old Oxford History volumes, Woodward especially, and the thought of actually writing them myself was beyond my wildest dreams; I met E.L. Woodward, the 'Age of Reform' man in the Senior Common Room after dinner in Corpus in 1966 when I got the fellowship and regarded him with such reverence that I didn’t dare tell him he had a crumb on his chin.